The saga of two plants — Sutter Energy and Colusa — helps explain in a microcosm how California came to have too much energy, and is paying a high price for it.

Sutter was built in 2001 by Houston-based Calpine, which owns 81 power plants in 18 states.

Independents like Calpine don’t have a captive audience of residential customers like regulated utilities do. Instead, they sell their electricity under contract or into the electricity market, and make money only if they can find customers for their power.

Sutter had the capacity to produce enough electricity to power roughly 400,000 homes. Calpine operated Sutter at an average of 50% of capacity in its early years — enough to make a profit.

But then Pacific Gas & Electric Co., a regulated, investor-owned utility, came along with a proposal to build Colusa.

It was not long after a statewide heat wave, and PG&E argued in its 2007 request seeking PUC approval that it needed the ability to generate more power. Colusa — a plant almost identical in size and technology to Sutter — was the only large-scale project that could be finished quickly, PG&E said.

More than a half-dozen opponents, including representatives of independent power plants, a municipal utilities group and consumer advocates filed objections questioning the utility company. Wasn’t there a more economical alternative? Did California need the plant at all?

They expressed concern that Colusa could be very expensive long-term for customers if it turned out that its power wasn’t needed.

That’s because public utilities such as PG&E operate on a different model.

If electricity sales don’t cover the operating and construction costs of an independent power plant, it can’t continue to run for long. And if the independent plant closes, the owner — and not ratepayers — bears the burden of the cost.

In contrast, publicly regulated utilities such as PG&E operate under more accommodating rules. Most of their revenue comes from electric rates approved by regulators that are set at a level to guarantee the utility recovers all costs for operating the electric system as well as the cost of building or buying a power plant — plus their guaranteed profit.

Protesters argued Colusa was unnecessary. The state’s excess production capacity by 2010, the year Colusa was slated to come online, was projected to be almost 25% — 10 percentage points higher than state regulatory requirements.

The looming oversupply, they asserted, meant that consumers would get stuck with much of the bill for Colusa no matter how little customers needed its electricity.

And the bill would be steep. Colusa would cost PG&E $673 million to build. To be paid off, the plant will have to operate until 2040. Over its lifetime, regulators calculated that PG&E will be allowed to charge more than $700 million to its customers to cover not just the construction cost but its operating costs and its profit.

The urgent push by PG&E “seems unwarranted and inappropriate, and potentially costly to ratepayers,” wrote Daniel Douglass, a lawyer for industry groups that represent independent power producers.

The California Municipal Utilities Assn. — whose members buy power from public utilities and then distribute that power to their customers — also complained in a filing that PG&E’s application appeared to avoid the issue of how Colusa’s cost would be shared if it ultimately sat idle. PG&E’s “application is confusing and contradicting as to whether or not PG&E proposes to have the issue of stranded cost recovery addressed,” wrote Scott Blaising, a lawyer representing the association. (“Stranded cost” is industry jargon for investment in an unneeded plant.)

The arguments over Colusa echoed warnings that had been made for years by Lynch, the former PUC commissioner.

A pro-consumer lawyer appointed PUC president in 2000 by Gov. Gray Davis, Lynch consistently argued as early as 2003 against building more power plants.

“I was like, ‘What the hell are we doing?’ ” recalled Lynch.

She often butted heads with other commissioners and utilities who pushed for more plants and more reserves. Midway though her term, the governor replaced her as president — with a former utility company executive.

One key battle was fought over how much reserve capacity was needed to guard against blackouts. Lynch sought to limit excess capacity to 9% of the state’s electricity needs. But in January 2004, over her objections, the PUC approved a gradual increase to 15% by 2008.

“We’ve created an extraordinarily complex system that gives you a carrot at every turn,” Lynch said. “I’m a harsh critic because this is intentionally complex to make money on the ratepayer’s back.”

With Lynch no longer on the PUC, the commissioners voted 5-0 in June 2008 to let PG&E build Colusa. The rationale: The plant was needed, notwithstanding arguments that there was a surplus of electricity being produced in the market.

PG&E began churning out power at Colusa in 2010. For the nearby Sutter plant, that marked the beginning of the end as its electricity sales plummeted.

In the years that followed, Sutter’s production slumped to about a quarter of its capacity, or just half the rate it had operated previously.

Calpine, Sutter’s owner, tried to drum up new business for the troubled plant, reaching out to shareholder-owned utilities such as PG&E and other potential buyers. Calpine even proposed spending $100 million to increase plant efficiency and output, according to a letter the company sent to the PUC in February 2012.

PG&E rejected the offer, Calpine said, “notwithstanding that Sutter may have been able to provide a lower cost.”

Asked for comment, PG&E said, “PG&E is dedicated to meeting the state’s clean energy goals in cost-effective ways for our customers. We use competitive bidding and negotiations to keep the cost and risk for our customers as low as possible.” It declined to comment further about its decision to build Colusa or on its discussions with Calpine.

Without new contracts and with energy use overall on the decline, Calpine had little choice but to close Sutter.

During a 2012 hearing about Sutter’s distress, one PUC commissioner, Mike Florio, acknowledged that the plant’s troubles were “just the tip of the proverbial iceberg.” He added, “Put simply, for the foreseeable future, we have more power plants than we need.”

Colusa, meanwhile, has operated at well below its generating capacity — just 47% in its first five years — much as its critics cautioned when PG&E sought approval to build it.

Sutter isn’t alone. Other natural gas plants once heralded as the saviors of California’s energy troubles have found themselves victims of the power glut. Independent power producers have announced plans to sell or close the 14-year-old Moss Landing power plant at Monterey Bay and the 13-year-old La Paloma facility in Kern County.

Robert Flexon, chief executive of independent power producer Dynegy Inc., which owns Moss Landing, said California energy policy makes it difficult for normal market competition. Independent plants are closing early, he said, because regulators favor utility companies over other power producers.

“It’s not a game we can win,” Flexon said.

Since 2008 alone — when consumption began falling — about 30 new power plants approved by California regulators have started producing electricity. These plants account for the vast majority of the 17% increase in the potential electricity supply in the state during that period.

Hundreds of other small power plants, with production capacities too low to require the same level of review by state regulators, have opened as well.

Most of the big new plants that regulators approved also operate at below 50% of their generating capacity.

So that California utilities can foot the bill for these plants, the amount they are allowed by regulators to charge ratepayers has increased to $40 billion annually from $33.5 billion, according to data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration. This has tacked on an additional $60 a year to the average residential power bill, adjusted for inflation.

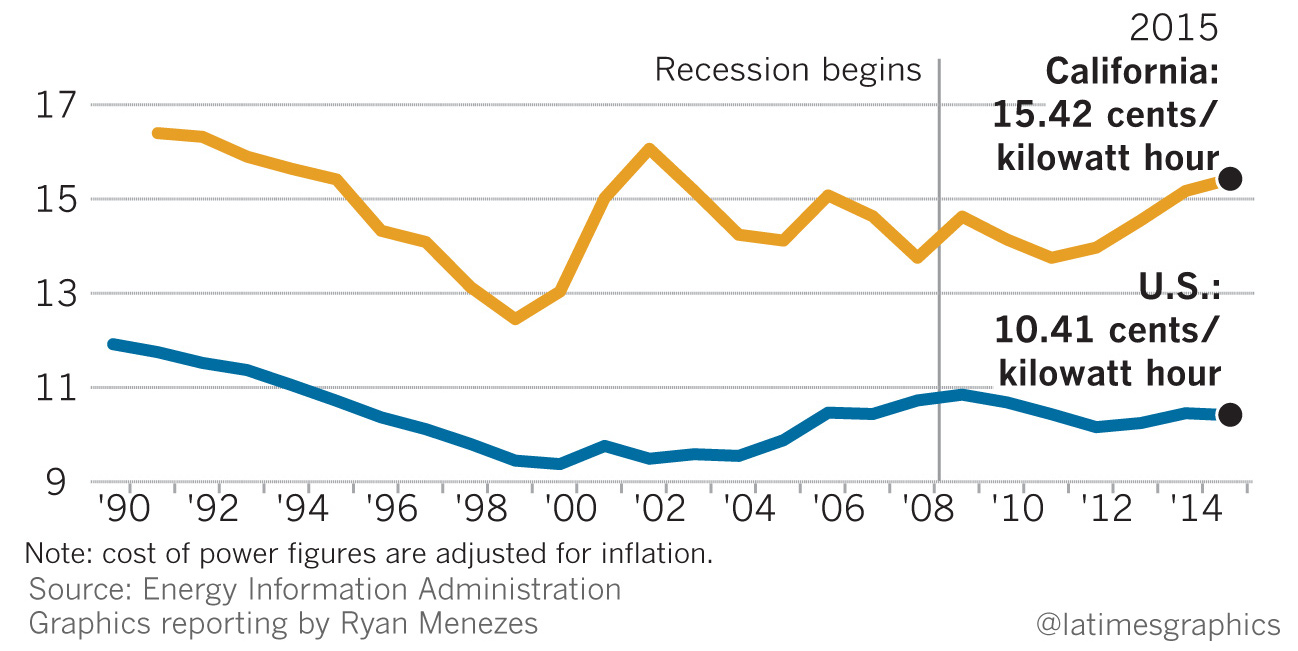

Another way of looking at the impact on consumers: The average cost of electricity in the state is now 15.42 cents a kilowatt hour versus 10.41 cents for users in the rest of the U.S. The rate in California, adjusted for inflation, has increased 12% since 2008, while prices have declined nearly 3% elsewhere in the country.

California utilities are “constantly crying wolf that we’re always short of power and have all this need,” said Bill Powers, a San Diego-based engineer and consumer advocate who has filed repeated objections with regulators to try to stop the approval of new plants. They are needlessly trying to attain a level of reliability that is a worst-case “act of God standard,” he said.

Even with the growing glut of electricity, consumer critics have found that it is difficult to block the PUC from approving new ones.

In 2010, regulators considered a request by PG&E to build a $1.15-billion power plant in Contra Costa County east of San Francisco, over objections that there wasn’t sufficient demand for its power. One skeptic was PUC commissioner Dian Grueneich. She warned that the plant wasn’t needed and its construction would lead to higher electricity rates for consumers — on top of the 28% increase the PUC had allowed for PG&E over the previous five years.

The PUC was caught in a “time warp,” she argued, in approving new plants as electricity use fell. “Our obligation is to ensure that our decisions have a legitimate factual basis and that ratepayers’ interest are protected.”

Her protests were ignored. By a 4-to-1 vote, with Grueneich the lone dissenter, the commissioners approved the building of the plant.

Consumer advocates then went to court to stop the project, resulting in a rare victory against the PUC. In February 2014, the California Court of Appeals overturned the commission, ruling there was no evidence the plant was needed.

Recent efforts to get courts to block several other PUC-approved plants have failed, however, so the projects are moving forward.

Contact the reporters. For more coverage follow @ivanlpenn and @ryanvmenezes

Times data editor Ben Welsh contributed to this report. Illustrations by Eben McCue. Graphics by Priya Krishnakumar and Paul Duginski. Produced by Lily Mihalik