One of the places we ran the “Can a computer make you cry?” [advertisement] was in Scientific American. Scientific American readers weren’t even playing videogames. Why the hell are you wasting any of this really expensive advertising? You’re competing with BMW for that ad.

— Trip Hawkins (EA Employee #1)

Consumers were looking for a brand signal for quality. They didn’t lionize the game makers as these creators to fawn over. They thought of the game makers almost as collaborators in their experience. So apostatizing didn’t make sense to the consumers.

— Bing Gordon (EA Employee #7)

In the ’80s that was an interesting experiment, that whole trying-to-make-them-into-rock-stars kind of thing. It was certainly a nice way to recruit top talent. But the reality is that computer programmers and artists and designers are not rock stars. It may have worked for the developers, but I don’t think it had any impact on consumers.

— Stewart Bonn (EA Employee #19)

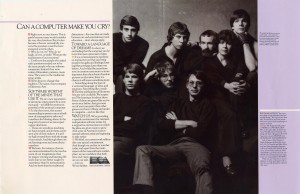

One of the stories that gamers most love to tell each other is that of Electronic Arts’s fall from grace. If you’re sufficiently interested in gaming history to be reading this blog, you almost certainly know the story in the broad strokes: how Trip Hawkins founded EA in 1982 as a haven for “software artists” doing cutting-edge work; how he put said artists front and center in rock-star-like poses in a series of iconic advertisements, the most famous of which asked whether a computer could make you cry; how he wrote on the back of every stylish EA “album cover” not about EA as a company but as “a collection of electronic artists who share a common goal to fulfill the potential of personal computing”; and how all the idealism somehow dissipated to give us the EA of today, a shambling behemoth that crushes more clever competitors under its sheer weight as it churns out sequel after sequel, retread after retread. The exact point where EA became the personification of everything retrograde and corporate in gaming varies with the teller; perhaps the closest thing to a popular consensus is the rise of John Madden Football and EA Sports in the early 1990s, when the last vestiges of software artistry in the company’s advertisements were replaced by jocks shouting, “It’s in the game!” Regardless of the specifics, though, everyone agrees that It All Went Horribly Wrong at some point. The story of EA has become gamers’ version of a Biblical tragedy: “For what shall it profit a man, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?”

Of course, as soon as one starts pulling out Bible quotes, it profits to ask whether one has gone too far. And, indeed, the story of EA is often over-dramatized and over-simplified. Questions of authenticity and creativity are always fraught; to imagine that anyone is really in the arts just for the art strikes me as hopelessly naive. The EA of the early 1980s wasn’t founded by artists but rather by businessmen, backed by venture capitalists with goals of their own that had little to do with “fulfilling the potential of personal computing.” Thus, when the software-artists angle turned out not to work so well, it didn’t take them long to pivot. This, then, is the history of that pivot, and how it led to the EA we know today.

Advertising is all about image making — about making others see you in the light in which you wish to be seen. Without realizing that they were doing anything of the sort, EA’s earliest marketers cemented an image into the historical imagination at the same time that they failed in their more practical task of crafting a message that resonated with the hoped-for customers of their own time. The very same early EA advertising campaign which speaks so eloquently to so many today actually missed the mark entirely in its own day, utterly failing to set the public imagination afire with this idea of programmers and game designers as rock stars. When Trip Hawkins sent Bill Budge — the programmer of his who most naturally resembled a rock star — on an autograph-signing tour of software stores and shopping malls, it didn’t lead to any outbreak of Budgomania. “Nobody would ever show up,” remembers Budge today, still wincing at the embarrassment of sitting behind a deserted autograph booth.

Nor were customers flocking into stores to buy the games EA’s rock stars had created. Sales remained far below initial projections during the eighteen months following EA’s official launch in June of 1983, and the company skated on the razor’s edge of bankruptcy on multiple occasions. While their first year yielded the substantial hits Pinball Construction Set, Archon, and One-on-One, 1984 could boast only one comparable success story, Seven Cities of Gold. Granted, four hits in two years was more than plenty of other publishers managed, but EA had been capitalized under the expectation that their games would open up whole new demographics for entertainment software. “The idea was to make games for 28-year-olds when everybody else was making games for 13-year-olds,” says Bing Gordon, Trip Hawkins’s old university roommate and right-hand man at EA. When those 28-year-olds failed to materialize, EA was left in the lurch.

![]()

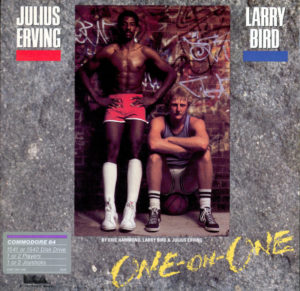

For better or for worse, One-on-One is the spiritual forefather of the unstoppable EA Sports lineup of today.

The most important architect of EA’s post-launch retrenchment was arguably neither Trip Hawkins nor Bing Gordon, but rather Larry Probst, who left the free-falling Activision to join EA as vice president for sales in 1984. Probst, who had worked at the dry-goods giants Johnson & Johnson and Clorox before joining Activision, had no particular attachment to the idea of software artists. He rather looked at the business of selling games much as he had that of selling toilet paper and bleach. He asked himself how EA could best make money in the market that existed rather than some fanciful new one they hoped to create. Steve Peterson, a product manager at EA, remembers that others “would still talk about how we were trying to create new forms of entertainment and break new boundaries.” But Probst, and increasingly Trip Hawkins as well, had the less high-minded goal of “going public and being a billion-dollar company.”

Probst had the key insight that distribution, more so than software artists or perhaps even product quality in the abstract, was the key to success in an industry that, following a major downturn in home computing in general in 1984, was only continuing to get more competitive. EA therefore spurned the existing distribution channels, which were nearly monopolized by SoftSel, the great behind-the-scenes power in the software industry to which everyone else was kowtowing; SoftSel’s head, Robert Leff, was the most important person in software that no one outside the industry had ever heard of. Instead of using SoftSel, EA set up their own distribution network piece by painful piece, beginning by cold-calling the individual stores and offering cut-rate deals in order to tempt them into risking the wrath of Leff and ordering from another source.

Then, once a reasonable distribution network was in place, EA leveraged the hell out of it by setting up a program of so-called “Affiliated Labels” — other publishers who would pay EA instead of a conventional distributor like SoftSel to get their products onto store shelves. It was a well-nigh revolutionary idea in game publishing, attractive to smaller publishers because EA was ready and able to help out with a whole range of the logistical difficulties they were always facing, from packaging and disk duplication to advertising campaigns. For EA, meanwhile, the Affiliated Labels yielded huge financial rewards and placed them in the driver’s seat of much of the industry, with the power of life and death over many of their smaller ostensible competitors.

Unsurprisingly, Activision, the only other publisher with comparable distributional clout, soon copied the idea, setting up a similar program of their own. But even as they did so, EA, seemingly always one step ahead, was becoming the first American publisher to send games — both their own and those of others — directly to Europe without going through a European intermediary like Britain’s U.S. Gold label.

![]()

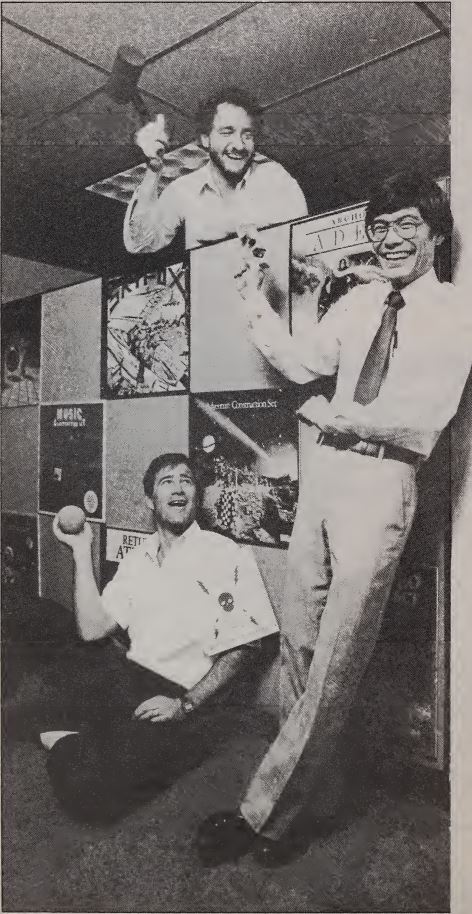

There was always something a bit contrived, in that indelible Silicon Valley way, about how EA chose to present themselves to the world. Here we have Bing Gordon, head of technology Greg Riker, and producer Joe Ybarra indulging in some of the creative play which, an accompanying article is at pains to tell us, was constantly going on around the office.

Larry Probst’s strategy of distribution über alles worked a treat, yielding explosive growth that more than made up for the company’s early struggles. In 1986, EA became the biggest computer-game publisher in the United States and the world, with annual revenues of $30 million. Their own games were doing well, but were assuming a very different character from the “simple, hot, and deep” ideal of the launch — a phrase Trip Hawkins had once loved to apply to games that were less stereotypically nerdy than the norm, that he imagined would be suitable for busy young adults with a finger on the pulse of hip pop culture. Now, having failed to attract that new demographic, EA adjusted their product line to appeal to those who were already buying computer games. A case in point was The Bard’s Tale, EA’s biggest hit of 1985, a hardcore CRPG that might take a hundred hours or more to complete — fodder for 13-year-olds with long summer vacations to fill rather than 28-year-olds with jobs and busy social calendars.

If “simple, hot, and deep” and programmers as rock stars had been two of the three pillars of EA’s launch philosophy, the last was the one written into Hawkins’s original mission statement as “stay with floppy-disk-based computers only.” Said statement had been written, we should remember, just as the first great videogame fad, fueled by the Atari VCS, was passing its peak and beginning the long plunge into what would go down in history as the Great Videogame Crash of 1983. At the time, it certainly wasn’t only the new EA who believed that the toy-like videogame consoles were the past, and that more sophisticated personal computers, running more sophisticated games, were the future. “I think that computer games are fundamentally different from videogames,” said Hawkins on the Computer Chronicles television show. “It becomes a question of program size, when you want to know how good a program can I have, how much can I do with it, and how long will it take before I’m bored with it.” This third pillar of EA’s strategy would take a bit longer to fall than the others, but fall it would.

The origins of EA’s loss of faith in the home computer in general as the ultimate winner of the interactive-entertainment platform wars can ironically be traced to their decision to wholeheartedly endorse one computer in particular. In October of 1984, Greg Riker, EA’s director of technology, got the chance to evaluate a prototype of Commodore’s upcoming Amiga. His verdict upon witnessing this first truly multimedia personal computer, with its superlative graphics and sound, was that this was the machine that could change everything, and that EA simply had to get involved with it as quickly as possible. He convinced Trip Hawkins of his point of view, and Hawkins managed to secure Amiga Prototype Number 12 for the company within weeks. In the months that followed, EA worked to advance the Amiga with if anything even more enthusiasm than Commodore themselves: developing libraries and programming frameworks which they shared with their outside developers; writing tools internally, including what would become the Amiga’s killer app, Deluxe Paint; documenting the Interchange File Format, a set of standard specifications for sharing pictures, sounds, animations, and music across applications. All of these things and more would remain a part of the Amiga platform’s basic software ecosystem throughout its existence.

When the Amiga finally started shipping late in 1985, EA actually made a far better public case for the machine than Commodore, taking out a splashy editorial-style advertisement just inside the cover of the premiere issue of the new AmigaWorld magazine. It showed the eight Amiga games EA would soon release and explained “why Electronic Arts is committed to the Amiga,” the latter headline appearing above a photograph of Trip Hawkins with his arm proprietorially draped over the Amiga on his desk.

![]()

Trip Hawkins with an Amiga

But it all turned into an immense disappointment. Initially, Commodore priced the Amiga wrong and marketed it worse, and even after they corrected some of their worst mistakes it perpetually under-performed in the American marketplace. For Hawkins and EA, the whole episode planted the first seeds of doubt as to whether home computers — which at the end of the day still were computers, requiring a degree of knowledge to operate and associated in the minds of most people more with work than pleasure — could really be the future of interactive entertainment as a mass-media enterprise. If a computer as magnificent as the Amiga couldn’t conquer the world, what would it take?

Perhaps it would take a piece of true consumer electronics, made by a company used to selling televisions and stereos to customers who expected to be able to just turn the things on and enjoy them — a company like, say, Philips, who were working on a new multimedia set-top box for the living room that they called CD-I. The name arose from the fact that it used the magical new technology of CD-ROM for storage, something EA had been begging Commodore to bring to the Amiga to no avail. EA embraced CD-I with the same enthusiasm they had recently shown for the Amiga, placing Greg Riker in personal charge of creating tools and techniques for programming it, working more as partners in CD-I’s development with Philips than as a mere third-party publisher.

Once again, however, it all came to nought. CD-I turned into one of the most notorious slow-motion fiascos in the history of the games industry, missing its originally planned release date in the fall of 1987 and then remaining vaporware for years on end. In early 1989, EA finally ran out of patience, mothballing all work on the platform unless and until it became a viable product; Greg Riker left the company to go work for Microsoft on their own CD-ROM research.

CD-I had cost EA a lot of money to no tangible result whatsoever, but it does reveal that the idea of gaming on something other than a conventional computer was no longer anathema to them. In fact, the year in which EA gave up on CD-I would prove the most pivotal of their entire history. We should therefore pause here to examine their position in 1989 in a bit more detail.

Despite the frustrating failure of the Amiga and CD-I to open a new golden age of interactive entertainment, EA wasn’t doing badly at all. Following years of steady growth, annual revenue had now reached $63 million, up 27 percent from 1988. EA was actively distributing about 100 titles under their own imprint, and 250 more under the imprint of the various Affiliated Labels, who had become absolutely key to their business model, accounting for some 45 percent of their total revenues. About 80 percent of their revenues still came from the United States, with 15 percent coming from Europe — where EA had set up a semi-independent subsidiary, the Langley, England-based EA Europe, in 1987 — and the remainder from the rest of the world. The company was extremely diversified. They were producing software for ten different computing platforms worldwide, had released 40 separate titles that had earned them at least $1 million each, and had no single title that accounted for more than 6 percent of their total revenues.

What we have here, then, is a very healthy business indeed, with multiple revenue streams and cash in the bank. The games they released were sometimes good, sometimes bad, sometimes mediocre; EA’s quality standards weren’t notably better or worse than the rest of their industry. “We tried to create a brand that fell somewhere between Honda and Mercedes,” admits Bing Gordon, “but a lot of the time we shipped Chevy.” Truth be told, even in the earliest days the rhetoric surrounding EA’s software artists had been a little overblown; many of the games their rock stars came up with were far less innovative than the advertising that accompanied them. The genius of Larry Probst had been to explicitly recognize that success or failure as a games publisher had as much to do with other factors as it did with the actual games you released.

For all their success, though, no one at EA was feeling particularly satisfied with their position. On the contrary: 1989 would go down in EA’s history as the year of “crisis.” As successful as they had become selling home-computer software, they remained big fish in a rather small pond, a situation out of keeping with the sense of overweening ambition that been a part of the company’s DNA since its founding. In 1989, about 4 million computers were being used to play games on a regular or semi-regular basis in American homes, enough to fuel a computer-game industry worth an estimated $230 million per year. EA alone owned more than 25 percent of that market, more than any competitor. But there was another, related market in which they had no presence at all: that of the videogame consoles, which had returned from the dead to haunt them even as they were consolidating their position as the biggest force in computer games. The country was in the grip of Nintendo mania. About 22 million Nintendo Entertainment Systems were already in American homes — a figure accounting for 24 percent of all American households — and cartridge-based videogames were selling to the tune of $1.6 billion per year.

Unlike many of their peers, EA hadn’t yet suffered all that badly under the Nintendo onslaught, largely because they had already diversified away from the Commodore 64, the low-end 8-bit computer which had been the largest gaming platform in the world just a couple of years before, and which the NES was now in the process of annihilating. But still, the future of the computer-games industry in general felt suddenly in doubt in a way that it hadn’t since at least the great home-computer downturn of 1984. A sizable coalition inside EA, including Larry Probst and most of the board of directors, pushed Trip Hawkins hard to get EA’s games onto the consoles. Fearing a coup, he finally came around. “We had to go into the [console-based] videogame business, and that meant the world of mass-market,” Hawkins remembers. “There were millions of customers we were going to reach.”

But through which door should they make their entrance? Accustomed to running roughshod over his Affiliated Labels, Hawkins wasn’t excited about the prospect of entering Nintendo’s walled garden, where the shoe would be on the other foot, thanks to that company’s infamously draconian rules for its licensees. Nintendo’s standard contract demanded that they receive the first $12 from every game a licensee sold, required every game to go through an exhaustive review process before publication, and placed strict limits on how many games a licensee was allowed to publish per year and how many units they were allowed to manufacture of each one. For EA, accustomed to being the baddest hombre in the Wild West that was the computer-game marketplace, this was well-nigh intolerable. Bing Gordon insists even today that, thanks to all of the fees and restrictions, no one other than Nintendo was doing much more than breaking even on the NES during this, the period that would go down in history as the platform’s golden age.

So, EA decided instead to back a dark horse: the much more modern Sega Genesis, which hadn’t even been released yet in North America. It was built around the same 16-bit Motorola 68000 CPU found in computers like the Commodore Amiga and Apple Macintosh, with audiovisual capabilities not all that far removed from the likes of the Amiga. The Genesis would give designers and programmers who were used to the affordances of full-fledged computers a far less limiting platform than the NES to work with, and it offered the opportunity to get it on the ground floor of a brand-new market, as opposed to the saturated NES platform. The only problem was that Sega’s licensing fees were comparable to those of Nintendo, even though they could only offer their licensees access to a much more uncertain pool of customers.

Determined to play hardball, Hawkins had a team of engineers reverse-engineer the Genesis, sufficient to let them write games for it with or without Sega’s official development kit. Then he met with Sega again, telling them that, if they refused to adjust their licensing terms, he would release games on the console without their blessing, forcing them to initiate an ugly court battle of the sort that was currently raging between Nintendo and Atari if they wished to bring him to heel. That, he was gambling, was expense and publicity of a sort which Sega simply couldn’t afford. And Sega evidently agreed with his assessment; they accepted a royalty rate half that being demanded by Nintendo. By this roundabout method, EA became the first major American publisher to support the new console, and from that point forward the two companies became, as Hawkins puts it, “good partners.”

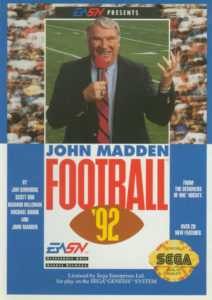

EA initially invested $2.5 million in ten games for the Genesis, some of them original to the console, some ports of their more popular computer games. They started shipping the first of them in June of 1990, ten months after the Genesis itself had first gone on sale in the United States. This first slate of EA Genesis titles arrived in a marketplace that was still starving for quality games, just as Hawkins had envisioned it would be. Among them was the game destined to become the face of the new, mass-market-oriented EA: John Madden Football, a more action-oriented re-imagining of a 1988 computer game of the same name.

![]()

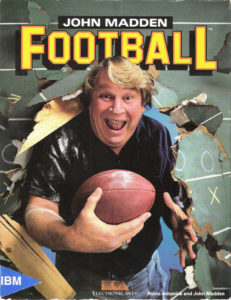

John Madden Football debuted as a rather cerebral, tactics-heavy computer game in 1988, just another in an EA tradition of famous-athlete-endorsed sports games stretching back to 1983’s (Dr. J and Larry Bird Go) One-on-One. No one in 1988 could have imagined what it would come to mean in the years to come for either its publisher or its spokesman/mascot, both of whom would ride it to iconic heights in American pop culture.

The Sega Genesis marked the third time EA had taken a leap of faith on a new platform. It was the first time, however, that their faith paid off. About 25 percent of the games EA sold in 1990 were for the Genesis. And when the console really started to take off in 1991, fueled not least by their own games, EA was there to reap the rewards. In that year, four of the ten best-selling Genesis games were published by EA. At the peak of their dominance, EA alone was publishing about 35 percent of all the games sold for the Genesis. Absent the boost their games gave it early on, it’s highly questionable whether the Genesis would have succeeded at all in the United States.

In the beginning, few of EA’s outside developers had been terribly excited about writing for the consoles. One of them remembers Hawkins “reading us the riot act” just to get them onboard. Indeed, Hawkins claims today that about 15 percent of EA’s internal employees were so unhappy with the new direction that they quit. Certainly his latest rhetoric could hardly have been more different from that of 1983:

I knew we had to let go of our attachment to machines that the public did not want to buy, and support the hardware that the public would embrace. I made this argument on the grounds of delivering customer satisfaction, and how quality is in the eye of the beholder. If the customer buys a Genesis, we want to give him the best we can for the machine he bought and not resent the consumer for not buying a $1000 computer.

By this point, Hawkins had finally bit the bullet and done a deal with Nintendo, who, in the face of multiple government investigations and lawsuits over their business practices, were becoming somewhat more generous with both their competitors and licensees. When games like Skate or Die, a port of a Commodore 64 hit that just happened to be perfect for the Nintendo and Sega demographics as well, started to sell in serious numbers on the consoles, Hawkins’s developers’ aversion started to fade in the face of all that filthy lucre. Soon the developers of Skate or Die were happily plunging into a sequel which would be a console exclusive.

Even the much-dreaded oversight role played by Nintendo, in which they reviewed every game before allowing it to be published, proved less onerous than expected. When Will Harvey, the designer of an action-adventure called The Immortal, finally steeled himself to look at Nintendo’s critique thereof, he was happily surprised to find the list of “suggestions” to be very helpful on the whole, demonstrating real sensitivity to the effect he was trying to achieve. Even Bing Gordon, who had been highly skeptical of getting into bed with Nintendo, had to admit in the end that “the rating system is fair. On a scale from zero to a hundred, where zero meant the system was totally manipulated for Nintendo’s self-interest and a hundred meant that it was absolutely democratic, they’d probably get a ninety. I’ve seen a little bit of self-interest, but this is America, the land of self-interest.”

![]()

Although EA cut their Nintendo teeth on the NES, it was on the long-awaited follow-up console, 1991’s Super Nintendo, that they really began to thrive. That machine boasted capabilities similar to those of the Sega Genesis, meaning EA already had games ready to port over, along with developers with considerable expertise in writing for a more advanced species of console. Just in time for the Christmas of 1991, EA released a new version of John Madden Football— John Madden Football ’92— simultaneously on the Super Nintendo and the Genesis. The sequel had been created, according to the recollections of several EA executives, against the advice of market researchers and retailers: “All you’re going to do is obsolete our old game.” But Trip Hawkins remembered how much, as a kid, he had loved the Strat-O-Matic Football board game, for which a new set of player and team cards was issued every year just before the beginning of football season, ensuring that you could always recreate in the board game the very same season you were watching every Sunday on television. So, he ignored the objections of the researchers and the retailers, and John Madden Football ’92 became an enormous hit, by far the biggest EA had yet enjoyed on any platform — thus inaugurating, for better or for worse, the tradition of annual versions of gaming’s most evergreen franchise. Like clockwork, we’ve gotten a new Madden every single year since, a span of time that numbers a quarter-century and change as of this writing.

All of this had a transformative effect on EA’s bottom line, bringing on their biggest growth spurt yet. Revenues increased from $78 million in 1990 to $113 million in 1991; then they jumped to $175 million in 1992, accompanied by a two-for-one stock split that was necessary to keep the share price, which had been at $10 just a few years before, from exceeding $50. In that year, six of the fifteen most popular console games, across all platforms, were published by EA. Their Sega Genesis games alone generated $77 million, 18 percent more than the entirety of the company’s product portfolio had managed in 1989. This was also the first year that EA’s console games in the aggregate outsold their offerings for computers. They were leaving no doubt now as to where their primary loyalty lay: “The 16-bit consoles are far better for games than PCs. The Genesis is a very sophisticated machine…” The disparity between the two sides of the company’s business would only continue to get more pronounced, as EA’s sales jumped by an extraordinary 70 percent — to $298 million — in 1993, a spurt fueled entirely by console-game sales.

But, despite all their success on the consoles, EA — and especially their founder, Trip Hawkins — continued to chafe under the restrictions of the walled-garden model of software distribution. Accordingly, Hawkins put together a group inside EA to research the potential for a CD-ROM-based multimedia setup box of their own, one that would be used for more than just playing games — sort of a CD-I done right. “The Japanese videogame companies,” he said, “are too shortsighted to see where this is going.” In contrast to their walled gardens, his box would be as open as possible. Rather than a single new hardware product, it would be a set of hardware specifications and an operating system which manufacturers could license, which would hopefully result in a situation similar to the MS-DOS marketplace, where lots of companies competed and innovated within the bounds of an established standard. The marketplace for games and applications as well on the new machine would be far less restricted than the console norm, with a more laissez-faire attitude to content and a royalty fee of just $3 per unit sold.

In 1991, EA spun off the venture under the name of 3DO. Hawkins turned most of his day-to-day responsibilities at EA over to Larry Probst in order to take personal charge of his new baby, which took tangible form for the first time with the release of the Panasonic “Real 3DO Player” in late 1993. It and other implementations of the 3DO technology managed to sell 500,000 units worldwide — 200,000 of them in North America — by January of 1995. Yet those numbers were still a pittance next to those of the dedicated game consoles, and the story of 3DO became one of constant flirtations with success that never quite led to that elusive breakthrough moment. As 3DO struggled, Hawkins’s relations with his old company worsened. He believed they had gone back on promises to support his new venture wholeheartedly; “I didn’t feel like I was leaving EA, but it turned out that way,” he says today with lingering bitterness. The long, frustrating saga of 3DO wouldn’t finally straggle to a bankruptcy until 2003.

EA, meanwhile, was flying ever higher absent their founder. Under Larry Probst — always the most hard-nosed and sober-minded of the executive staff, the person most laser-focused on the actual business of selling videogames — EA cemented their reputation as the conservative, risk-averse giant of their industry. This new EA was seemingly the polar opposite of the company that had once asked with almost painful earnestness if a computer could make you cry. And yet, paradoxically, it was a place still inhabited by a surprising number of the people who had come up with that message. Most prominent among them was Bing Gordon, who notes cryptically today only that “people’s ideals get tested in the face of love or money.” Part of the problem — assuming one judges EA’s current less-than-boldly-innovative lineup of franchises to be a problem — may be a simple buildup of creative cruft that has resulted from being in business for so long. Every franchise that debuts in inspiration and innovation, then goes on to join John Madden Football on the list of EA perennials, sucks some of the bandwidth away that might otherwise have been devoted to the next big innovator.

In the summer of 1987, when EA was still straddling the line between their old personality and their new, Trip Hawkins wrote the following lines in their official newsletter — lines which evince the keenly felt tension between art and commerce that has become the defining aspect of EA’s corporate history for so many in the years since:

Unfortunately, simply being creative doesn’t always mean you’ll be wildly successful. Van Gogh sold only one painting during his lifetime. Lots of people would still rather go see Porky’s Revenge IV, ignoring well-produced movies like Amadeus or Chariots of Fire. As a result, film producers take fewer risks, and we get less variety, and pretty soon the Porky’s and Rambo clones are all you can find on a Friday night. Software developers have the same problem. (To this day, all of us M.U.L.E. fans wonder why the entire world hasn’t fallen in love with our favorite game.)

The only way to solve the problem is to do it together. On our end, we’ll keep innovating, researching, experimenting with new ways to use this new medium; on your end, you can support our efforts by taking an occasional risk, by buying something new and different… maybe Robot Rascals, or Make Your Own Murder Party.

You may be very pleasantly surprised — and you’ll help our software artists live to innovate another day.

Did EA go the direction they did because of gamers’ collective failure to support their most innovative, experimental work? Does it even matter if so? The more pragmatic among us might note that the EA of today is delivering games that millions upon millions of people clearly want to play, and where’s the harm in that?

Still, as we look upon this industry that has so steadfastly refused to grow up in so many ways, there remain always those pictures of EA’s first generation of software artists — pictures that, yes, are a little bit pretentious and a lot contrived, but that nevertheless beckon us to pursue higher ideals. They’ve taken on an identity of their own now, quite apart from the history of the company that once splashed them across the pages of glossy lifestyle magazines. Long may they continue to inspire.

![]()

(Sources: the book Gamers at Work: Stories Behind the Games People Play by Morgan Ramsay and Game Over: How Nintendo Conquered the World by David Sheff; Harvard Business School’s case study “Electronic Arts in 1995”; ACE of April 1990; Amazing Computing of July 1992; Computer Gaming World of March 1988, October 1988, and June 1989; MicroTimes of April 1986; The One of November 1988; Electronic Arts’s newsletter Farther from Summer 1987; AmigaWorld premiere issue; materials relating to the Software Publishers Association included in the Brøderbund archive at the Strong Museum of Play; the episode of the Computer Chronicles television series entitled “Computer Games.” Online sources include “We See Farther — A History of Electronic Arts” at Gamasutra, “How Electronic Arts Lost Its Soul” at Polygon, and Funding Universe‘s history of Electronic Arts.)

![]()