In this post, we learn how to return from exceptions correctly. In the course of this, we will explore the iretq instruction, the C calling convention, multimedia registers, and the red zone.

As always, the complete source code is on Github. Please file issues for any problems, questions, or improvement suggestions. There is also a gitter chat and a comment section at the end of this page.

Introduction

Most exceptions are fatal and can’t be resolved. For example, we can’t return from a divide-by-zero exception in a reasonable way. However, there are some exceptions that we can resolve:

Imagine a system that uses memory mapped files: We map a file into the virtual address space without loading it into memory. Whenever we access a part of the file for the first time, a page fault occurs. However, this page fault is not fatal. We can resolve it by loading the corresponding page from disk into memory and setting the present flag in the page table. Then we can return from the page fault handler and restart the failed instruction, which now successfully accesses the file data.

Memory mapped files are completely out of scope for us right now (we have neither a file concept nor a hard disk driver). So we need an exception that we can resolve easily so that we can return from it in a reasonable way. Fortunately, there is an exception that needs no resolution at all: the breakpoint exception.

The Breakpoint Exception

The breakpoint exception is the perfect exception to test our upcoming return-from-exception logic. Its only purpose is to temporary pause a program when the breakpoint instruction int3 is executed.

The breakpoint exception is commonly used in debuggers: When the user sets a breakpoint, the debugger overwrites the corresponding instruction with the int3 instruction so that the CPU throws the breakpoint exception when it reaches that line. When the user wants to continue the program, the debugger replaces the int3 instruction with the original instruction again and continues the program. For more details, see the How debuggers work series.

For our use case, we don’t need to overwrite any instructions (it wouldn’t even be possible since we set the page table flags to read-only). Instead, we just want to print a message when the breakpoint instruction is executed and then continue the program.

Catching Breakpoints

Let’s start by defining a handler function for the breakpoint exception:

// in src/interrupts/mod.rsextern"C"fnbreakpoint_handler(stack_frame:*constExceptionStackFrame)->!{unsafe{print_error(format_args!("EXCEPTION: BREAKPOINT at {:#x}\n{:#?}",(*stack_frame).instruction_pointer,*stack_frame));}loop{}}We print a red error message using print_error and also output the instruction pointer and the rest of the stack frame. Note that this function does not return yet, since our handler! macro still requires a diverging function.

We need to register our new handler function in the interrupt descriptor table (IDT):

// in src/interrupts/mod.rslazy_static!{staticrefIDT:idt::Idt={letmutidt=idt::Idt::new();idt.set_handler(0,handler!(divide_by_zero_handler));idt.set_handler(3,handler!(breakpoint_handler));// newidt.set_handler(6,handler!(invalid_opcode_handler));idt.set_handler(14,handler_with_error_code!(page_fault_handler));idt};}We set the IDT entry with number 3 since it’s the vector number of the breakpoint exception.

Testing it

In order to test it, we insert an int3 instruction in our rust_main:

// in src/lib.rs...#[macro_use]// needed for the `int!` macroexterncratex86;...#[no_mangle]pubextern"C"fnrust_main(...){...interrupts::init();// trigger a breakpoint exceptionunsafe{int!(3)};println!("It did not crash!");loop{}}When we execute make run, we see the following:

It works! Now we “just” need to return from the breakpoint handler somehow so that we see the It did not crash message again.

Returning from Exceptions

So how do we return from exceptions? To make it easier, we look at a normal function return first:

When calling a function, the call instruction pushes the return address on the stack. When the called function is finished, it can return to the parent function through the ret instruction, which pops the return address from the stack and then jumps to it.

The exception stack frame, in contrast, looks a bit different:

Instead of pushing a return address, the CPU pushes the stack and instruction pointers (with their segment descriptors), the RFLAGS register, and an optional error code. It also aligns the stack pointer to a 16 byte boundary before pushing values.

So we can’t use a normal ret instruction, since it expects a different stack frame layout. Instead, there is a special instruction for returning from exceptions: iretq.

The iretq Instruction

The iretq instruction is the one and only way to return from exceptions and is specifically designed for this purpose. The AMD64 manual (PDF) even demands that iretq“must be used to terminate the exception or interrupt handler associated with the exception”.

IRETQ restores rip, cs, rflags, rsp, and cs from the values saved on the stack and thus continues the interrupted program. The instruction does not handle the optional error code, so it must be popped from the stack before.

We see that iretq treats the stored instruction pointer as return address. For most exceptions, the stored rip points to the instruction that caused the fault. So by executing iretq, we restart the failing instruction. This makes sense because we should have resolved the exception when returning from it, so the instruction should no longer fail (e.g. the accessed part of the memory mapped file is now present in memory).

The situation is a bit different for the breakpoint exception, since it needs no resolution. Restarting the int3 instruction wouldn’t make sense, since it would cause a new breakpoint exception and we would enter an endless loop. For this reason the hardware designers decided that the stored rip should point to the next instruction after the int3 instruction.

Let’s check this for our breakpoint handler. Remember, the handler printed the following message (see the image above):

EXCEPTION: BREAKPOINT at 0x1100aaSo let’s disassemble the instruction at 0x1100aa and its predecessor:

> objdump -d build/kernel-x86_64.bin | grep -B1 "1100aa:"

1100a9: cc int3 1100aa: 4889 c6 mov %rax,%rsiWe see that 0x1100aa indeed points to the next instruction after int3. So we can simply jump to the stored instruction pointer when we want to return from the breakpoint exception.

Implementation

Let’s update our handler! macro to support non-diverging exception handlers:

// in src/interrupts/mod.rsmacro_rules!handler{($name:ident)=>{{#[naked]extern"C"fnwrapper()->!{unsafe{asm!("mov rdi, rsp sub rsp, 8 // align the stack pointer call $0"::"i"($nameasextern"C"fn(*constExceptionStackFrame))// no longer diverging:"rdi":"intel","volatile");// newasm!("add rsp, 8 // undo stack pointer alignment iretq"::::"intel","volatile");::core::intrinsics::unreachable();}}wrapper}}}When an exception handler returns from the call instruction, we use the iretq instruction to continue the interrupted program. Note that we need to undo the stack pointer alignment before, so that rsp points to the end of the exception stack frame again.

We’ve changed the handler function type, so we need to adjust our existing exception handlers:

// in src/interrupts/mod.rs

extern "C" fn divide_by_zero_handler(

- stack_frame: *const ExceptionStackFrame) -> ! {...}+ stack_frame: *const ExceptionStackFrame) {...}

extern "C" fn invalid_opcode_handler(

- stack_frame: *const ExceptionStackFrame) -> ! {...}+ stack_frame: *const ExceptionStackFrame) {...}

extern "C" fn breakpoint_handler(

- stack_frame: *const ExceptionStackFrame) -> ! {+ stack_frame: *const ExceptionStackFrame) {

unsafe { print_error(...) }- loop {}

}Note that we also removed the loop {} at the end of our breakpoint_handler so that it no longer diverges. The divide_by_zero_handler and the invalid_opcode_handler still diverge (albeit the new function type would allow a return).

Testing

Let’s try our new iretq logic:

Instead of the expected “It did not crash” message after the breakpoint exception, we get a page fault. The strange thing is that our kernel tried to access address 0x0, which should never happen. So it seems like we messed up something important.

Debugging

Let’s debug it using GDB. For that we execute make debug in one terminal (which starts QEMU with the -s -S flags) and then make gdb (which starts and connects GDB) in a second terminal. For more information about GDB debugging, check out our Set Up GDB guide.

First we want to check if our iretq was successful. Therefore we set a breakpoint on the println!("It did not crash line!") statement in src/lib.rs. Let’s assume that it’s on line 61:

(gdb) break blog_os/src/lib.rs:61

Breakpoint 1 at 0x110a95: file /home/.../blog_os/src/lib.rs, line 61.This line is after the int3 instruction, so we know that the iretq succeeded when the breakpoint is hit. To test this, we continue the execution:

(gdb) continue

Continuing.

Breakpoint 1, blog_os::rust_main (multiboot_information_address=1539136)

at /home/.../blog_os/src/lib.rs:61

61 println!("It did not crash!");

It worked! So our kernel successfully returned from the int3 instruction, which means that the iretq itself works.

However, when we continue the execution again, we get the page fault. So the exception occurs somewhere in the println logic. This means that it occurs in code generated by the compiler (and not e.g. in inline assembly). But the compiler should never access 0x0, so how is this happening?

The answer is that we’ve used the wrong calling convention for our exception handlers. Thus, we violate some compiler invariants so that the code that works fine without intermediate exceptions starts to violate memory safety when it’s executed after a breakpoint exception.

Calling Conventions

Exceptions are quite similar to function calls: The CPU jumps to the first instruction of the (handler) function and executes the function. Afterwards, if the function is not diverging, the CPU jumps to the return address and continues the execution of the parent function.

However, there is a major difference between exceptions and function calls: A function call is invoked voluntary by a compiler inserted call instruction, while an exception might occur at any instruction. In order to understand the consequences of this difference, we need to examine function calls in more detail.

Calling conventions specify the details of a function call. For example, they specify where function parameters are placed (e.g. in registers or on the stack) and how results are returned. On x86_64 Linux, the following rules apply for C functions (specified in the System V ABI):

- the first six integer arguments are passed in registers

rdi,rsi,rdx,rcx,r8,r9 - additional arguments are passed on the stack

- results are returned in

raxandrdx

Note that Rust does not follow the C ABI (in fact, there isn’t even a Rust ABI yet). So these rules apply only to functions declared as extern "C" fn.

Preserved and Scratch Registers

The calling convention divides the registers in two parts: preserved and scratch registers.

The values of the preserved register must remain unchanged across function calls. So a called function (the “callee”) is only allowed to overwrite these registers if it restores their original values before returning. Therefore these registers are called “callee-saved”. A common pattern is to save these registers to the stack at the function’s beginning and restore them just before returning.

In contrast, a called function is allowed to overwrite scratch registers without restrictions. If the caller wants to preserve the value of a scratch register across a function call, it needs to backup and restore it (e.g. by pushing it to the stack before the function call). So the scratch registers are caller-saved.

On x86_64, the C calling convention specifies the following preserved and scratch registers:

| preserved registers | scratch registers |

|---|---|

rbp, rbx, rsp, r12, r13, r14, r15 | rax, rcx, rdx, rsi, rdi, r8, r9, r10, r11 |

| callee-saved | caller-saved |

The compiler knows these rules, so it generates the code accordingly. For example, most functions begin with a push rbp, which backups rbp on the stack (because it’s a callee-saved register).

The Exception Calling Convention

In contrast to function calls, exceptions can occur on any instruction. In most cases we don’t even know at compile time if the generated code will cause an exception. For example, the compiler can’t know if an instruction causes a stack overflow or an other page fault.

Since we don’t know when an exception occurs, we can’t backup any registers before. This means that we can’t use a calling convention that relies on caller-saved registers for our exception handlers. But we do so at the moment: Our exception handlers are declared as extern "C" fn and thus use the C calling convention.

So here is what happens:

rust_mainis executing; it writes some memory address intorax.- The

int3instruction causes a breakpoint exception. - Our

breakpoint_handlerprints to the screen and assumes that it can overwriteraxfreely (since it’s a scratch register). Somehow the value0ends up inrax. - We return from the breakpoint exception using

iretq. rust_maincontinues and accesses the memory address inrax.- The CPU tries to access address

0x0, which causes a page fault.

So our exception handler erroneously assumes that the scratch registers were saved by the caller. But the caller (rust_main) couldn’t save any registers since it didn’t know that an exception occurs. So nobody saves rax and the other scratch registers, which leads to the page fault.

The problem is that we use a calling convention with caller-saved registers for our exception handlers. Instead, we need a calling convention means that preserves all registers. In other words, all registers must be callee-saved:

extern"all-registers-callee-saved"fnexception_handler(){...}Unfortunately, Rust does not support such a calling convention. It was proposed once, but did not get accepted for various reasons. The primary reason was that such calling conventions can be simulated by writing a naked wrapper function.

(Remember: Naked functions are functions without prologue and can contain only inline assembly. They were discussed in the previous post.)

A naked wrapper function

Such a naked wrapper function might look like this:

#[naked]extern"C"fncalling_convention_wrapper(){unsafe{asm!(" push rax push rcx push rdx push rsi push rdi push r8 push r9 push r10 push r11 // TODO: call exception handler with C calling convention pop r11 pop r10 pop r9 pop r8 pop rdi pop rsi pop rdx pop rcx pop rax "::::"intel","volatile");}}This wrapper function saves all scratch registers to the stack before calling the exception handler and restores them afterwards. Note that we pop the registers in reverse order.

We don’t need to backup preserved registers since they are callee-saved in the C calling convention. Thus, the compiler already takes care of preserving their values.

Fixing our Handler Macro

Let’s update our handler macro to fix the calling convention problem. Therefore we need to backup and restore all scratch registers. For that we create two new macros:

// in src/interrupts/mod.rsmacro_rules!save_scratch_registers{()=>{asm!("push rax push rcx push rdx push rsi push rdi push r8 push r9 push r10 push r11 "::::"intel","volatile");}}macro_rules!restore_scratch_registers{()=>{asm!("pop r11 pop r10 pop r9 pop r8 pop rdi pop rsi pop rdx pop rcx pop rax "::::"intel","volatile");}}We need to declare these macros above our handler macro, since macros are only available after their declaration.

Now we can use these macros to fix our handler! macro:

// in src/interrupts/mod.rsmacro_rules!handler{($name:ident)=>{{#[naked]extern"C"fnwrapper()->!{unsafe{save_scratch_registers!();asm!("mov rdi, rsp add rdi, 9*8 // calculate exception stack frame pointer // sub rsp, 8 (stack is aligned already) call $0"::"i"($nameasextern"C"fn(*constExceptionStackFrame)):"rdi":"intel","volatile");restore_scratch_registers!();asm!(" // add rsp, 8 (undo stack alignment; not needed anymore) iretq"::::"intel","volatile");::core::intrinsics::unreachable();}}wrapper}}}It’s important that we save the registers first, before we modify any of them. After the call instruction (but before iretq) we restore the registers again. Because we’re now changing rsp (by pushing the register values) before we load it into rdi, we would get a wrong exception stack frame pointer. Therefore we need to adjust it by adding the number of bytes we push. We push 9 registers that are 8 bytes each, so 9 * 8 bytes in total.

Note that we no longer need to manually align the stack pointer, because we’re pushing an uneven number of registers in save_scratch_registers. Thus the stack pointer already has the required 16-byte alignment.

Testing it again

Let’s test it again with our corrected handler! macro:

The page fault is gone and we see the “It did not crash” message again!

So the page fault occurred because our exception handler didn’t preserve the scratch register rax. Our new handler! macro fixes this problem by saving all scratch registers (including rax) before calling exception handlers. Thus, rax still contains the valid memory address when rust-main continues execution.

When we discussed calling conventions above, we assummed that a x86_64 CPU only has the following 16 registers: rax, rbx, rcx, rdx, rsi, rdi, rsp, rbp, r8, r9, r10, r11.r12, r13, r14, and r15. These registers are called general purpose registers since each of them can be used for arithmetic and load/store instructions.

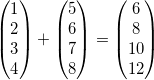

However, modern CPUs also have a set of special purpose registers, which can be used to improve performance in several use cases. On x86_64, the most important set of special purpose registers are the multimedia registers. These registers are larger than the general purpose registers and can be used to speed up audio/video processing or matrix calculations. For example, we could use them to add two 4-dimensional vectors in a single CPU instruction:

Such multimedia instructions are called Single Instruction Multiple Data (SIMD) instructions, because they simultaneously perform an operation (e.g. addition) on multiple data words. Good compilers are able to transform normal loops into such SIMD code automatically. This process is called auto-vectorization and can lead to huge performance improvements.

However, auto-vectorization causes a problem for us: Most of the multimedia registers are caller-saved. According to our discussion of calling conventions above, this means that our exception handlers erroneously assume that they are allowed to overwrite them without preserving their values.

We don’t use any multimedia registers explicitly, but the Rust compiler might auto-vectorize our code (including the exception handlers). Thus we could silently clobber the multimedia registers, which leads to the same problems as above:

This example shows a program that is using the first three multimedia registers (mm0 to mm2). At some point, an exception occurs and control is transfered to the exception handler. The exception handler uses mm1 for its own data and thus overwrites the previous value. When the exception is resolved, the CPU continues the interrupted program again. However, the program is now corrupt since it relies on the original mm1 value.

Saving and Restoring Multimedia Registers

In order to fix this problem, we need to backup all caller-saved multimedia registers before we call the exception handler. The problem is that the set of multimedia registers varies between CPUs. There are different standards:

- MMX: The MMX instruction set was introduced in 1997 and defines eight 64 bit registers called

mm0throughmm7. These registers are just aliases for the registers of the x87 floating point unit. - SSE: The Streaming SIMD Extensions instruction set was introduced in 1999. Instead of re-using the floating point registers, it adds a completely new register set. The sixteen new registers are called

xmm0throughxmm15and are 128 bits each. - AVX: The Advanced Vector Extensions are extensions that further increase the size of the multimedia registers. The new registers are called

ymm0throughymm15and are 256 bits each. They extend thexmmregisters, so e.g.xmm0is the lower (or upper?) half ofymm0.

The Rust compiler (and LLVM) assume that the x86_64-unknown-linux-gnu target supports only MMX and SSE, so we don’t need to save the ymm0 through ymm15. But we need to save xmm0 through xmm15 and also mm0 through mm7. There is a special instruction to do this: fxsave. This instruction saves the floating point and multimedia state to a given address. It needs 512 bytes to store that state.

In order to save/restore the multimedia registers, we could add new macros:

macro_rules!save_multimedia_registers{()=>{asm!("sub rsp, 512 fxsave [rsp] "::::"intel","volatile");}}macro_rules!restore_multimedia_registers{()=>{asm!("fxrstor [rsp] add rsp, 512 "::::"intel","volatile");}}First, we reserve the 512 bytes on the stack and then we use fxsave to backup the multimedia registers. In order to restore them later, we use the fxrstor instruction. Note that fxsave and fxrstor require a 16 byte aligned memory address.

However, we won’t do it that way. The problem is the large amount of memory required. We will reuse the same code when we handle hardware interrupts in a future post. So for each mouse click, pressed key, or arrived network package we need to write 512 bytes to memory. This would be a huge performance problem.

Fortunately, there exists an alternative solution.

Disabling Multimedia Extensions

We just disable MMX, SSE, and all the other fancy multimedia extensions. This way, our exception handlers won’t clobber the multimedia registers because they won’t use them at all.

This solution has its own disadvantages, of course. For example, it leads to slower kernel code because the compiler can’t perform any auto-vectorization optimizations. But it’s still the faster solution (since we save many memory accesses) and most kernels do it this way (including Linux).

So how do we disable MMX and SSE? Well, we just tell the compiler that our target system doesn’t support it. Since the very beginning, we’re compiling our kernel for the x86_64-unknown-linux-gnu target. This worked fine so far, but now we want a different target without support for multimedia extensions. We can do so by creating a target configuration file.

Target Specifications

In order to disable the multimedia extensions for our kernel, we need to compile for a custom target. We want a target that is equal to x86_64-unknown-linux-gnu, but without MMX and SSE support. Rust allows us to specify such a target using a JSON configuration file.

A minimal target specification that describes the x86_64-unknown-linux-gnu target looks like this:

{"llvm-target":"x86_64-unknown-linux-gnu","data-layout":"e-m:e-i64:64-f80:128-n8:16:32:64-S128","target-endian":"little","target-pointer-width":"64","arch":"x86_64","os":"none"}The llvm-target field specifies the target triple that is passed to LLVM. We want to derive a 64-bit Linux target, so we choose x86_64-unknown-linux-gnu. The data-layout field is also passed to LLVM and specifies how data should be laid out in memory. It consists of various specifications seperated by a - character. For example, the e means little endian and S128 specifies that the stack should be 128 bits (= 16 byte) aligned. The format is described in detail in the LLVM documentation but there shouldn’t be a reason to change this string.

The other fields are used for conditional compilation. This allows crate authors to use cfg variables to write special code for depending on the OS or the architecture. There isn’t any up-to-date documentation about these fields but the corresponding source code is quite readable.

Disabling MMX and SSE

In order to disable the multimedia extensions, we create a new target named x86_64-blog_os. To describe this target, we create a file named x86_64-blog_os.json in the project root with the following content:

{"llvm-target":"x86_64-unknown-linux-gnu","data-layout":"e-m:e-i64:64-f80:128-n8:16:32:64-S128","target-endian":"little","target-pointer-width":"64","arch":"x86_64","os":"none","features":"-mmx,-sse"}It’s equal to x86_64-unknown-linux-gnu target but has one additional option: "features": "-mmx,-sse". So we added two target features: -mmx and -sse. The minus prefix defines that our target does not support this feature. So by specifying -mmx and -sse, we disable the default mmx and sse features.

In order to compile for the new target, we need to adjust our Makefile:

# in `Makefile`

arch ?= x86_64

-target ?= $(arch)-unknown-linux-gnu+target ?= $(arch)-blog_os

...The new target name (x86_64-blog_os) is the file name of the JSON configuration file without the .json extension.

Cross compilation

Let’s try if our kernel still works with the new target:

> make run

Compiling raw-cpuid v2.0.1

Compiling rlibc v0.1.5

Compiling x86 v0.7.1

Compiling spin v0.3.5

error[E0463]: can't find crate for `core`

error: aborting due to previous error

Build failed, waiting for other jobs to finish...

...

Makefile:52: recipe for target 'cargo' failed

make: *** [cargo] Error 101

It doesn’t compile anymore. The error tells us that the Rust compiler no longer finds the core library.

The core library is implicitly linked to all no_std crates and contains things such as Result, Option, and iterators. We’ve used that library without problems since the very beginning, so why is it no longer available?

The problem is that the core library is distributed together with the Rust compiler as a precompiled library. So it is only valid for the host triple, which is x86_64-unknown-linux-gnu in our case. If we want to compile code for other targets, we need to recompile core for these targets first.

Xargo

That’s where xargo comes in. It is a wrapper for cargo that eases cross compilation. We can install it by executing:

cargo install xargoIf the installation fails, make sure that you have cmake and the OpenSSL headers installed. For more details, see the xargo’s dependency section.

Xargo is “a drop-in replacement for cargo”, so every cargo command also works with xargo. You can do e.g. xargo --help, xargo clean, or xargo doc. However, the build command gains additional functionality: xargo build will automatically cross compile the core library (and a few other libraries such as alloc and collections) when compiling for custom targets.

That’s exactly what we want, so we change one letter in our Makefile:

# in `Makefile`

...

cargo:

- @cargo build --target $(target)+ @xargo build --target $(target)

...Now the build goes through xargo, which should fix the compilation error. Let’s try it out:

> make run

Downloading https://static.rust-lang.org/dist/2016-09-19/rustc-nightly-src.tar.gz

Unpacking rustc-nightly-src.tar.gz

Compiling sysroot for x86_64-blog_os

Compiling core v0.0.0

LLVM ERROR: SSE register return with SSE disabled

error: Could not compile `core`.

Well, we get a different error now, so it seems like we’re making progress :).

We see that xargo downloads the corresponding source code for our Rust nightly from the Rust servers and then compiles a new sysroot for our new target. A sysroot contains the various pre-compiled crates such as core, alloc, and collections.

However, a strange error occurs when compiling core:

LLVM ERROR: SSE register return with SSE disabledIt seems like there is a “SSE register return” although SSE is disabled. But what’s an “SSE register return”?

SSE Register Return

Remember when we discussed calling conventions above? The calling convention defines which registers are used for return values. Well, the System V ABI defines that xmm0 should be used for returning floating point values. So somewhere in the core library a function returns a float and LLVM doesn’t know what to do. The ABI says “use xmm0” but the target specification says “don’t use xmm registers”.

In order to fix this problem, we need to change our float ABI. The idea is to avoid normal hardware-supported floats and use a pure software implementation instead. We can do so by enabling the soft-float feature for our target. For that, we edit x86_64-blog_os.json:

{"llvm-target":"x86_64-unknown-linux-gnu",..."features":"-mmx,-sse,+soft-float"}The plus prefix tells LLVM to enable the soft-float feature.

Let’s try make run again:

> make run

Compiling sysroot for x86_64-blog_os

Compiling core v0.0.0 (file:///home/…/.xargo/src/libcore)

Compiling rustc_unicode v0.0.0 (file:///home/…/.xargo/src/librustc_unicode)

Compiling rand v0.0.0 (file:///home/…/.xargo/src/librand)

Compiling alloc v0.0.0 (file:///home/…/.xargo/src/liballoc)

Compiling collections v0.0.0 (file:///home/…/.xargo/src/libcollections)

Finished release [optimized] target(s) in 40.35 secs

Compiling once v0.3.2

Compiling bitflags v0.4.0

Compiling bit_field v0.1.0

Compiling x86 v0.7.1

Compiling linked_list_allocator v0.2.2

Compiling raw-cpuid v2.0.1

Compiling spin v0.3.5

Compiling multiboot2 v0.1.0

Compiling rlibc v0.1.5

Compiling spin v0.4.3

Compiling bitflags v0.7.0

Compiling lazy_static v0.2.1

Compiling hole_list_allocator v0.1.0

Compiling blog_os v0.1.0

warning: unused result which must be used…

warning: unused variable: `allocator`…

warning: unused variable: `frame`…

Finished debug [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 6.62 secs

It worked! We see that xargo now successfully compiles the sysroot crates (including core) in release mode. Then it starts the normal cargo build, which now succeeds since the required core, alloc, and collection libraries are now available.

Note that cargo needs to recompile all dependencies too, since it needs to generate different code for the new target. If you’re getting an error about a missing compiler-rt library, try updating to the newest nightly (compiler-rt was removed in PR #35021).

Now we have a kernel that never touches the multimedia registers! We can verify this by executing:

> objdump -d build/kernel-x86_64.bin | grep "mm[0-9]"If the command produces no output, our kernel uses neither MMX (mm0– mm7) nor SSE (xmm0– xmm15) registers.

So now our return-from-exception logic works without problems in most cases. However, there is still a pitfall hidden in the C calling convention, which might cause hideous bugs in some rare cases.

The Red Zone

The red zone is an optimization of the System V ABI that allows functions to temporary use the 128 bytes below its stack frame without adjusting the stack pointer:

The image shows the stack frame of a function with n local variables. On function entry, the stack pointer is adjusted to make room on the stack for the local variables.

The red zone is defined as the 128 bytes below the adjusted stack pointer. The function can use this area for temporary data that’s not needed across function calls. Thus, the two instructions for adjusting the stack pointer can be avoided in some cases (e.g. in small leaf functions).

However, this optimization leads to huge problems with exceptions. Let’s assume that an exception occurs while a function uses the red zone:

The CPU and the exception handler overwrite the data in red zone. But this data is still needed by the interrupted function. So the function won’t work correctly anymore when we return from the exception handler. It might fail or cause another exception, but it could also lead to strange bugs that take weeks to debug.

Adjusting our Exception Handler?

The problem is that the System V ABI demands that the red zone “shall not be modified by signal or interrupt handlers.” Our current exception handlers do not respect this. We could try to fix it by subtracting 128 from the stack pointer before pushing anything:

subrsp,128save_scratch_registers()...call......restore_scratch_registers()addrsp,128iretqThis will not work. The problem is that the CPU pushes the exception stack frame before even calling our handler function. So the CPU itself will clobber the red zone and there is nothing we can do about that. So our only chance is to disable the red zone.

Disabling the Red Zone

The red zone is a property of our target, so in order to disable it we edit our x86_64-blog_os.json a last time:

{"llvm-target":"x86_64-unknown-linux-gnu",..."features":"-mmx,-sse,+soft-float","disable-redzone":true}We add one additional option at the end: "disable-redzone": true. As you might guess, this option disables the red zone optimization.

Now we have a red zone free kernel!

Exceptions with Error Codes

We’re now able to correctly return from exceptions without error codes. However, we still can’t return from exceptions that push an error code (e.g. page faults). Let’s fix that by updating our handler_with_error_code macro:

// in src/interrupts/mod.rsmacro_rules!handler_with_error_code{($name:ident)=>{{#[naked]extern"C"fnwrapper()->!{unsafe{asm!("pop rsi // pop error code into rsi mov rdi, rsp sub rsp, 8 // align the stack pointer call $0"::"i"($nameasextern"C"fn(*constExceptionStackFrame,u64)):"rdi","rsi":"intel");asm!("iretq"::::"intel","volatile");::core::intrinsics::unreachable();}}wrapper}}}First, we change the type of the handler function: no more -> !, so it no longer needs to diverge. We also add an iretq instruction at the end.

Now we can make our page_fault_handler non-diverging:

// in src/interrupts/mod.rs

extern "C" fn page_fault_handler(stack_frame: *const ExceptionStackFrame,

- error_code: u64) -> ! { ... }+ error_code: u64) { ... }However, now we have the same problem as above: The handler function will overwrite the scratch registers and cause bugs when returning. Let’s fix this by invoking save_scratch_registers at the beginning:

// in src/interrupts/mod.rsmacro_rules!handler_with_error_code{($name:ident)=>{{#[naked]extern"C"fnwrapper()->!{unsafe{save_scratch_registers!();asm!("pop rsi // pop error code into rsi mov rdi, rsp add rdi, 10*8 // calculate exception stack frame pointer sub rsp, 8 // align the stack pointer call $0 add rsp, 8 // undo stack pointer alignment "::"i"($nameasextern"C"fn(*constExceptionStackFrame,u64)):"rdi","rsi":"intel");restore_scratch_registers!();asm!("iretq"::::"intel","volatile");::core::intrinsics::unreachable();}}wrapper}}}iretq. Like in the handler macro, we now need to add 10*8 to rdi in order to get the correct exception stack frame pointer (save_scratch_registers pushes nine 8 byte registers, plus the error code). We also need to undo the stack pointer alignment after the call .Now we have one last bug: We pop the error code into rsi, but the error code is no longer at the top of the stack (since save_scratch_registers pushed 9 registers on top of it). So we need to do it differently:

// in src/interrupts/mod.rsmacro_rules!handler_with_error_code{($name:ident)=>{{#[naked]extern"C"fnwrapper()->!{unsafe{save_scratch_registers!();asm!("mov rsi, [rsp + 9*8] // load error code into rsi mov rdi, rsp add rdi, 10*8 // calculate exception stack frame pointer sub rsp, 8 // align the stack pointer call $0 add rsp, 8 // undo stack pointer alignment "::"i"($nameasextern"C"fn(*constExceptionStackFrame,u64)):"rdi","rsi":"intel");restore_scratch_registers!();asm!("add rsp, 8 // pop error code iretq"::::"intel","volatile");::core::intrinsics::unreachable();}}wrapper}}}Instead of using pop, we’re calculating the error code address manually (save_scratch_registers pushes nine 8 byte registers) and load it into rsi using a mov. So now the error code stays on the stack. But iretq doesn’t handle the error code, so we need to pop it before invoking iretq.

Phew! That was a lot of fiddling with assembly. Let’s test if it still works.

Testing

First, we test if the exception stack frame pointer and the error code are still correct:

// in rust_main in src/lib.rs...unsafe{int!(3)};// provoke a page faultunsafe{*(0xdeadbeafas*mutu64)=42;}println!("It did not crash!");loop{}This should cause the following error message:

EXCEPTION: PAGE FAULT while accessing 0xdeadbeaf

error code: CAUSED_BY_WRITE

ExceptionStackFrame {

instruction_pointer: 1114753,

code_segment: 8,

cpu_flags: 2097158,

stack_pointer: 1171104,

stack_segment: 16

}The error code should still be CAUSED_BY_WRITE and the exception stack frame values should also be correct (e.g. code_segment should be 8 and stack_segment should be 16).

Page Faults as Breakpoints

We didn’t test returns from the page fault handler yet. In order to test our iretq logic, we temporary define accesses to 0xdeadbeaf as legal. They should behave exactly like the breakpoint exception: Print an error message and then continue with the next instruction.

Therefore we update our page_fault_handler:

// in src/interrupts/mod.rsextern"C"fnpage_fault_handler(stack_frame:*constExceptionStackFrame,error_code:u64){usex86::controlregs;unsafe{print_error(...);}// newunsafe{ifcontrolregs::cr2()==0xdeadbeaf{letstack_frame=&mut*(stack_frameas*mutExceptionStackFrame);stack_frame.instruction_pointer+=7;return;}}loop{}}If the accessed memory address is 0xdeadbeaf (the CPU stores this information in the cr2 register), we don’t loop endlessly. Instead we update the stored instruction pointer and return. Remember, the normal behavior when returning from a page fault is to restart the failing instruction. We don’t want that, so we manipulate the stored instruction pointer to point to the next instruction.

In our case, the page fault is caused by the instruction at address 1114753, which is 0x110281 in hexadecimal. Let’s examine this instruction using objdump:

> objdump -d build/kernel-x86_64.bin | grep "110281"

110281: 48 c7 02 2a 00 00 00 movq $0x2a,(%rdx)It’s a movq instruction with the 7 byte opcode 48 c7 02 2a 00 00 00. So the next instruction starts 7 bytes after.

Thus, we can jump to the next instruction in our page_fault_handler by adding 7 to the instruction pointer. This is a horrible hack, since the page fault could also be caused by other instructions with different opcode lengths. But it’s good enough for a quick test.

When we execute make run now, we should see the “It did not crash” message after the page fault:

Our iretq logic seems to work!

Let’s quickly remove the 0xdeadbeaf hack from our page_fault_handler again and pretend that we’ve never done that :).

What’s next?

We are now able to catch exceptions and to return from them. However, there are still exceptions that completely crash our kernel by causing a triple fault. In the next post, we will fix this issue by handling a special type of exception: the double fault. Thus, we will be able to avoid random reboots in our kernel.