I think I first heard about the Zstandard compression algorithm at a Mercurial developer sprint in 2015. At one end of a large table a few people were uttering expletives out of sheer excitement. At developer gatherings, that's the universal signal for something is awesome. Long story short, a Facebook engineer shared a link to theRealTime Data Compression blog operated by Yann Collet (then known as the author of LZ4 - a compression algorithm known for its insane speeds) and people were completely nerding out over the excellent articles and the data within showing the beginnings of a new general purpose lossless compression algorithm named Zstandard. It promised better-than-deflate/zlib compression ratios and performance on both compression and decompression. This being a Mercurial meeting, many of us were intrigued because zlib is used by Mercurial for various functionality (including on-disk storage and compression over the wire protocol) and zlib operations frequently appear as performance hot spots.

Before I continue, if you are interested in low-level performance and software optimization, I highly recommend perusing theRealTime Data Compression blog. There are some absolute nuggets of info in there.

Anyway, over the months, the news about Zstandard (zstd) kept getting better and more promising. As the 1.0 release neared, the Facebook engineers I interact with (Yann Collet - Zstandard's author - is now employed by Facebook) were absolutely ecstatic about Zstandard and its potential. I was toying around with pre-release versions and was absolutely blown away by the performance and features. I believed the hype.

Zstandard 1.0 wasreleased on August 31, 2016. A few days later, I started thepython-zstandard project to provide a fully-featured and Pythonic interface to the underlying zstd C API while not sacrificing safety or performance. The ulterior motive was to leverage those bindings in Mercurial so Zstandard could be a first class citizen in Mercurial, possibly replacing zlib as the default compression algorithm for all operations.

Fast forward six months and I've achieved many of those goals. python-zstandard has a nearly complete interface to the zstd C API. It even exposes some primitives not in the C API, such as batch compression operations that leverage multiple threads and use minimal memory allocations to facilitate insanely fast execution. (Expect a dedicated post on python-zstandard from me soon.)

Mercurial 4.1 ships with the python-zstandard bindings. Two Mercurial 4.1 peers talking to each other will exchange Zstandard compressed data instead of zlib. For a Firefox repository clone, transfer size is reduced from ~1184 MB (zlib level 6) to ~1052 MB (zstd level 3) in the default Mercurial configuration while using ~60% of the CPU that zlib required on the compressor end. When cloning from hg.mozilla.org, the pre-generated zstd clone bundle hosted on a CDN using maximum compression is ~707 MB - ~60% the size of zlib! And, work is ongoing for Mercurial to support Zstandard for on-disk storage, which should bring considerable performance wins over zlib for local operations.

I've learned a lot working on python-zstandard and integrating Zstandard into Mercurial. My primary takeaway is Zstandard is awesome.

In this post, I'm going to extol the virtues of Zstandard and provide reasons why I think you should use it.

Why Zstandard

The main objective of lossless compression is to spend one resource (CPU) so that you may reduce another (I/O). This trade-off is usually made because data - either at rest in storage or in motion over a network or even through a machine via software and memory - is a limiting factor for performance. So if compression is needed for your use case to mitigate I/O being the limiting resource and you can swap in a different compression algorithm that magically reduces both CPU and I/O requirements, that's pretty exciting. At scale, better and more efficient compression can translate to substantial cost savings in infrastructure. It can also lead to improved application performance, translating to better end-user engagement, sales, productivity, etc. This is why companies like Facebook (Zstandard), Google (brotli, snappy, zopfli), andPied Piper (middle-out) invest in compression.

Today, the most widely used compression algorithm in the world is likely DEFLATE. And, software most often interacts with DEFLATE via what is likely the most widely used software library in the world, zlib.

Being at least 27 years old, DEFLATE is getting a bit long in the tooth. Computers are completely different today than they were in 1990. The Pentium microprocessor debuted in 1993. If memory serves (pun intended), it used PC66 DRAM, which had a transfer rate of 533 MB/s. For comparison, a modern NVMe M.2 SSD (like the Samsung 960 PRO) can read at 3000+ MB/s and write at 2000+ MB/s. In other words, persistent storage today is faster than the RAM from the era when DEFLATE was invented. And of course CPU and network speeds have increased as well. We also have completely different instruction sets on CPUs for well-designed algorithms and software to take advantage of. What I'm trying to say is the market is ripe for DEFLATE and zlib to be dethroned by algorithms and software that take into account the realities of modern computers.

(For the remainder of this post I'll use zlib as a stand-in forDEFLATE because it is simpler.)

Zstandard initially piqued my attention by promising better-than-zlib compression and performance in both the compression and decompression directions. That's impressive. But it isn't unique. Brotli achieves the same, for example. But what kept my attention was Zstandard's rich feature set, tuning abilities, and therefore versatility.

In the sections below, I'll describe some of the benefits of Zstandard in more detail.

Before I do, I need to throw in an obligatory disclaimer about data and numbers that I use. Benchmarking is hard. Benchmarks should not be trusted. There are so many variables that can influence performance and benchmarks. (A recent example that surprised me is theCPU frequency/power ramping properties of Xeon versus non-Xeon Intel CPUs. tl;dr a Xeon won't hit max CPU frequency if only a core or two is busy, meaning that any single or low-threaded benchmark is likely misleading on Xeons unless you change power settings to mitigate its conservative power ramping defaults. And if you change power settings, does that reflect real-life usage?)

Reporting useful and accurate performance numbers for compression is hard because there are so many variables to care about. For example:

- Every corpus is different. Text, JSON, C++, photos, numerical data, etc all exhibit different properties when fed into compression and could cause compression ratios or speeds to vary significantly.

- Few large inputs versus many smaller inputs (some algorithms work better on large inputs; some libraries have high per-operation overhead).

- Memory allocation and use strategy. Performance can vary significantly depending on how a compression library allocates, manages, and uses memory. This can be an implementation specific detail as opposed to a core property of the compression algorithm.

Since Mercurial is the driver for my work in Zstandard, the data and

numbers I report in this post are mostly Mercurial data. Specifically,

I'll be referring to data in themozilla-unified Firefox repository.

This repository contains over 300,000 commits spanning almost 10 years.

The data within is a good mix of text (mostly C++, JavaScript, Python,

HTML, and CSS source code and other free-form text) and binary (like

PNGs). The Mercurial layer adds some binary structures to e.g. represent

metadata for deltas, diffs, and patching. There are two Mercurial-specific

pieces of data I will use. One is a Mercurial bundle. This is essentially

a representation of all data in a repository. It stores a mix of raw,

fulltext data and deltas on that data. For the mozilla-unified repo, an

uncompressed bundle (produced via hg bundle -t none-v2 -a) is ~4457 MB.

The other piece of data is revlog chunks. This is a mix of fulltext

and delta data for a specific item tracked in version control. I

frequently use the changelog corpus, which is the fulltext data

describing changesets or commits to Firefox. The numbers quoted and

used for charts in this postare available in a Google Sheet.

All performance data was obtained on an i7-6700K running Ubuntu 16.10 (Linux 4.8.0) with a mostly stock config. Benchmarks were performed in memory to mitigate storage I/O or filesystem interference. Memory used is DDR4-2133 with a cycle time of 35 clocks.

While I'm pretty positive about Zstandard, it isn't perfect. There are corpora for which Zstandard performs worse than other algorithms, even ones I compare it directly to in this post. So, your mileage may vary. Please enlighten me with your counterexamples by leaving a comment.

With that (rather large) disclaimer out of the way, let's talk about what makes Zstandard awesome.

Flexibility for Speed Versus Size Trade-offs

Compression algorithms typically contain parameters to control how much work to do. You can choose to spend more CPU to (hopefully) achieve better compression or you can spend less CPU to sacrifice compression. (OK, fine, there are other factors like memory usage at play too. I'm simplifying.) This is commonly exposed to end-users as a compression level. (In reality there are often multiple parameters that can be tuned. But I'll just use level as a stand-in to represent the concept.)

But even with adjustable compression levels, the performance of many compression algorithms and libraries tend to fall within a relatively narrow window. In other words, many compression algorithms focus on niche markets. For example, LZ4 is super fast but doesn't yield great compression ratios. LZMA yields terrific compression ratios but is extremely slow.

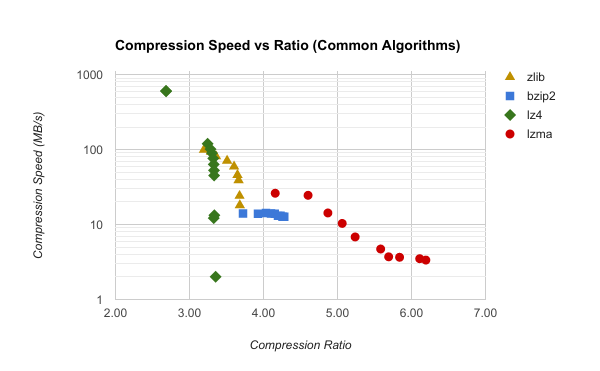

This can be visualized in the following chart showing results when compressing a mozilla-unified Mercurial bundle:

This chart plots the logarithmic compression speed in megabytes per second against achieved compression ratio. The further right a data point is, the better the compression and the smaller the output. The higher up a point is, the faster compression is.

The ideal compression algorithm lives in the top right, which means it compresses well and is fast. But the powers of mathematics push compression algorithms away from the top right.

On to the observations.

LZ4 is highly vertical, which means its compression ratios are limited in variance but it is extremely flexible in speed. So for this data, you might as well stick to a lower compression level because higher values don't buy you much.

Bzip2 is the opposite: a horizontal line. That means it is consistently the same speed while yielding different compression ratios. In other words, you might as well crank bzip2 up to maximum compression because it doesn't have a significant adverse impact on speed.

LZMA and zlib are more interesting because they exhibit more variance in both the compression ratio and speed dimensions. But let's be frank, they are still pretty narrow. LZMA looks pretty good from a shape perspective, but its top speed is just too slow - only ~26 MB/s!

This small window of flexibility means that you often have to choose a compression algorithm based on the speed versus size trade-off you are willing to make at that time. That choice often gets baked into software. And as time passes and your software or data gains popularity, changing the software to swap in or support a new compression algorithm becomes harder because of the cost and disruption it will cause. That's technical debt.

What we really want is a single compression algorithm that occupies lots of space in both dimensions of our chart - a curve that has high variance in both compression speed and ratio. Such an algorithm would allow you to make an easy decision choosing a compression algorithm without locking you into a narrow behavior profile. It would allow you make a completely different size versus speed trade-off in the future by only adjusting a config knob or two in your application - no swapping of compression algorithms needed!

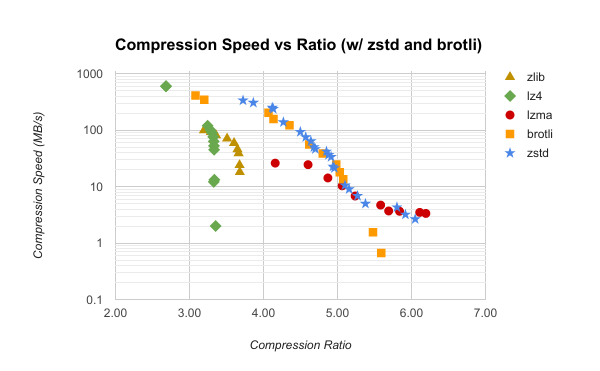

As you can guess, Zstandard fulfills this role. This can clearly be seen in the following chart (which also adds brotli for comparison).

The advantages of Zstandard (and brotli) are obvious. Zstandard's compression speeds go from ~338 MB/s at level 1 to ~2.6 MB/s at level 22 while covering compression ratios from 3.72 to 6.05. On one end, zstd level 1 is ~3.4x faster than zlib level 1 while achieving better compression than zlib level 9! That fastest speed is only 2x slower than LZ4 level 1. On the other end of the spectrum, zstd level 22 runs ~1 MB/s slower than LZMA at level 9 and produces a file that is only 2.3% larger.

It's worth noting that zstd's C API exposes several knobs for tweaking the compression algorithm. Each compression level maps to a pre-defined set of values for these knobs. It is possible to set these values beyond the ranges exposed by the default compression levels 1 through 22. I've done some basic experimentation with this and have made compression even faster (while sacrificing ratio, of course). This covers the gap between Zstandard and brotli on this end of the tuning curve.

The wide span of compression speeds and ratios is a game changer for compression. Unless you have special requirements such as lightning fast operations (which LZ4 can provide) or special corpora that Zstandard can't handle well, Zstandard is a very safe and flexible choice for general purpose compression.

Multi-threaded Compression

Zstd 1.1.3 contains a multi-threaded compression API that allows a compression operation to leverage multiple threads. The output from this API is compatible with the Zstandard frame format and doesn't require any special handling on the decompression side. In other words, a compressor can switch to the multi-threaded API and decompressors won't care.

This is a big deal for a few reasons. First, today's advancements in computer processors tend to yield more capacity from more cores not from faster clocks and better cycle efficiency (although many cases do benefit greatly from modern instruction sets like AVX and therefore better cycle efficiency). Second, so many compression libraries are only single-threaded and require consumers to invent their own framing formats or storage models to facilitate multi-threading. (SeeBlosc for such a library.) Lack of a multi-threaded API in the compression library means trusting another piece of software or writing your own multi-threaded code.

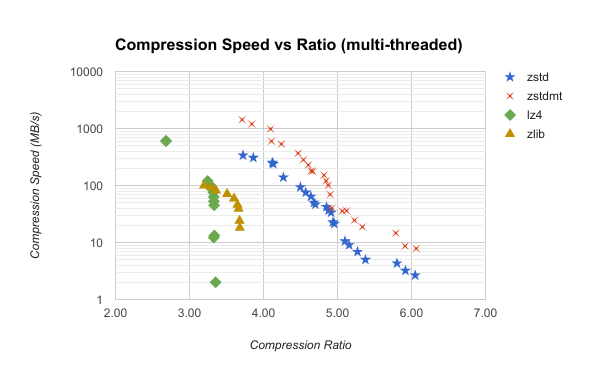

The following chart adds a plot of Zstandard multi-threaded compression with 4 threads.

The existing curve for Zstandard basically shifted straight up. Nice!

The ~338 MB/s speed for single-threaded compression on zstd level 1 increases to ~1,376 MB/s with 4 threads. That's ~4.06x faster. And, it is ~2.26x faster than the previous fastest entry, LZ4 at level 1! The output size only increased by ~4 MB or ~0.3% over single-threaded compression.

The scaling properties for multi-threaded compression on this input are terrific: all 4 cores are saturated and the output size barely changed.

Because Zstandard's multi-threaded compression API produces data compatible with any Zstandard decompressor, it can logically be considered an extension of compression levels. This means that the already extremely flexible speed vs ratio curve becomes even wider in the speed axis. Zstandard was already a justifiable choice with its extreme versatility. But when you throw in native multi-threaded compression API support, the flexibility for tuning compression performance is just absurd. With enough cores, you are likely to run into I/O limits long before you exhaust the CPU, at which point you can crank up the compression level and sacrifice as much CPU as you are willing to burn. That's a good position to be in.

Decompression Speed

Compression speed and ratios only tell half the story about a compression algorithm. Except for archiving scenarios where you write once and read rarely, you probably care about decompression performance.

Popular compression algorithms like zlib and bzip2 have less than stellar decompression speeds. On my i7-6700K, zlib decompression can deliver many decompressed data sets at the output end at 200+ MB/s. However, on the input/compressed end, it frequently fails to reach 100 MB/s or even 80 MB/s. This is significant because if your application is reading data over a 1 Gbps network or from a local disk (modern SSDs can read at several hundred MB/s or more), then your application has a CPU bottleneck at decoding the data - and that's before you actually do anything useful with the data in the application layer! (Remember: the idea behind compression is to spend CPU to mitigate an I/O bottleneck. So if compression makes you CPU bound, you've undermined the point of compression!) And if my Skylake CPU running at 4.0 GHz is CPU - not I/O - bound, A Xeon in a data center will be even slower and even more CPU bound (Xeons tend to run at much lower clock speeds - the laws of thermodynamics require that in order to run more cores in the package). In short, if you are using zlib for high throughput scenarios, there's a good chance it is a bottleneck and slowing down your application.

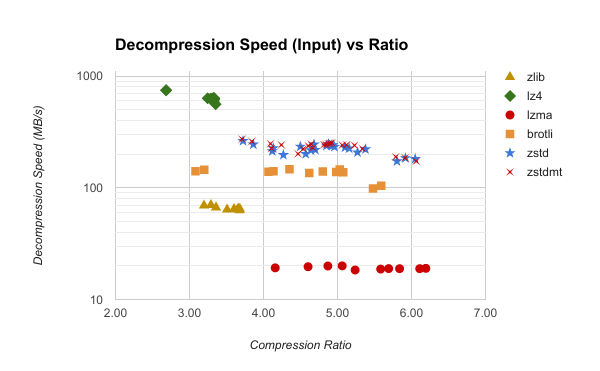

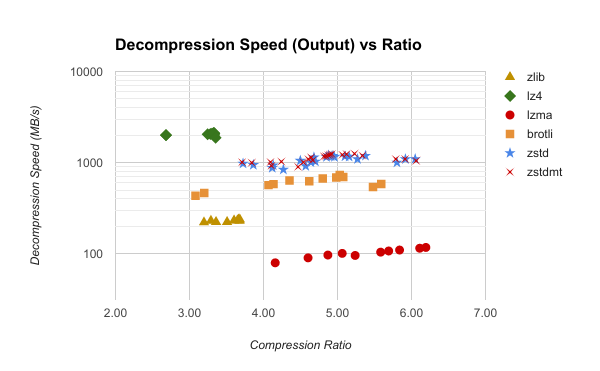

We again measure the speed of algorithms using a Firefox Mercurial bundle. The following charts plot decompression speed versus ratio for this file. The first chart measures decompression speed on the input end of the decompressor. The second measures speed at the output end.

Zstandard matches its great compression speed with great decompression speed. Zstandard can deliver decompressed output at 1000+ MB/s while consuming input at 200-275MB/s. Furthermore, decompression speed is mostly independent of the compression level. (Although higher compression levels require more memory in the decompressor.) So, if you want to throw more CPU at re-compression later so data at rest takes less space, you can do that without sacrificing read performance. I haven't done the math, but there is probably a break-even point where having dedicated machines re-compress terabytes or petabytes of data at rest offsets the costs of those machine through reduced storage costs.

While Zstandard is not as fast decompressing as LZ4 (which can consume compressed input at 500+ MB/s), its performance is often ~4x faster than zlib. On many CPUs, this puts it well above 1 Gbps, which is often desirable to avoid a bottleneck at the network layer.

It's also worth noting that while Zstandard and brotli were comparable on the compression half of this data, Zstandard has a clear advantage doing decompression.

Finally, you don't appear to pay a price for multi-threaded Zstandard

compression on the decompression side (zstdmt in the chart).

Dictionary Support

The examples so far in this post have used a single 4,457 MB piece of input data to measure behavior. Large data can behave completely differently from small data. This is because so much of what compression algorithms do is find patterns that came before so incoming data can be referenced to old data instead of uniquely stored. And if data is small, there isn't much of it that came before to reference!

This is often why many small, independent chunks of input compress poorly compared to a single large chunk. This can be demonstrated by comparing the widely-used zip and tar archive formats. On the surface, both do the same thing: they are a container of files. But they employ compression at different phases. A zip file will zlib compress each entry independently. However, a tar file doesn't use compression internally. Instead, the tar file itself is fed into a compression algorithm and compressed as a whole.

We can observe the difference on real world data. Firefox

ships with a file named omni.ja. Despite the weird extension, this

is a zip file. The file contains most of the assets for non-compiled

code used by Firefox. This includes the JavaScript, HTML, CSS, and

images that power many parts of the Firefox frontend. The file weighs

in at 9,783,749 bytes for the 64-bit Windows Firefox Nightly from

2017-03-06. (Or 9,965,793 bytes when using zip -9 - the code for

generating omni.ja is smarter than zip and creates smaller

files.) But a zlib level 9 compressed tar.gz file of that directory

is 8,627,155 bytes. That 1,156KB / 13% size difference is significant

when you are talking about delivering bits to end users! (In this

case, the content within the archive needs to be individually

addressable to facilitate fast access to any item without having

to decompress the entire archive: this matters for performance.)

A more extreme example of the differences between zip and tar is the files in the Firefox source checkout. On revision a08ec245fa24 of the Firefox Mercurial repository, a zip file of all files in version control is 430,446,549 bytes versus 322,916,403 bytes for a tar.gz file (1,177,430,383 bytes uncompressed spanning 180,912 files). Using Zstandard, compressing each file discretely at compression level 3 yields 391,387,299 bytes of compressed data versus 294,926,418 as a single stream (without thetar container). Same compression algorithm. Different application method. Drastically different results. That's the impact of input size on compression performance.

While the compression ratio and speed of a single large stream is

often better than multiple smaller chunks, there are still

use cases that either don't have enough data or prefer independent

access to each piece of input (like Firefox's omni.ja file). So

a robust compression algorithm should handle small inputs as well

as it does large inputs.

Zstandard helps offset the inherent inefficiencies of small inputs by supporting dictionary compression. A dictionary is essentially data used to seed the compressor's state. If the compressor sees data that exists in the dictionary, it references the dictionary instead of storing new data in the compressed output stream. This results in smaller output sizes and better compression ratios. One drawback to this is the dictionary has to be used to decompress data, which means you need to figure out how to distribute the dictionary and ensure it remains in sync with all data producers and consumers. This isn't always trivial.

Dictionary compression only works if there is enough repeated data and patterns in the inputs that can be extracted to yield a useful dictionary. Examples of this include markup languages, source code, or pieces of similar data (such as JSON payloads from HTTP API requests or telemetry data), which often have many repeated keywords and patterns.

Dictionaries are typically produced by training them on existing data. Essentially, you feed a bunch of samples into an algorithm that spits out a meaningful and useful dictionary. The more coherency in the data that will be compressed, the better the dictionary and the better the compression ratios.

Dictionaries can have a significant effect on compression ratios and speed.

Let's go back to Firefox's omni.ja file. Compressing each file

discretely at zstd level 12 yields 9,177,410 bytes of data. But if

we produce a 131,072 byte dictionary by training it on all files

within omni.ja, the total size of each file compressed discretely

is 7,942,886 bytes. Including the dictionary, the total size is

8,073,958 bytes, 1,103,452 bytes smaller than non-dictionary

compression! (The zlib-based omni.ja is 9,783,749 bytes.) So

Zstandard plus dictionary compression would likely yield a

meaningful ~1.5 MB size reduction to the omni.ja file. This would

make the Firefox distribution smaller and may improve startup

time (since many files inside omni.ja are accessed at

startup), which would make a number of people very happy. (Of

course, Firefox doesn't yet contain the zstd C library. And adding

it just for this use case may not make sense. But Firefox does ship

with the brotli library and brotli supports dictionary compression

and has similar performance characteristics as Zstandard, so, uh,

someone may want to look into transitioning omni.jar tonot zlib.)

But the benefits of dictionary compression don't end at compression ratios: operations with dictionaries can be faster as well!

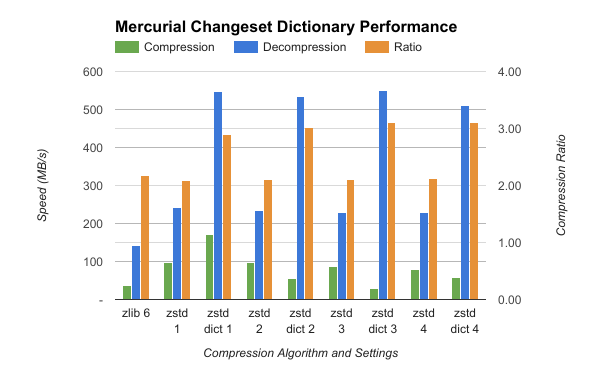

The following chart shows performance when compressing Mercurialchangeset data (describes a Mercurial commit) for the Firefox repository. There are 382,530 discrete inputs spanning 221,429,458 bytes (mean: 579 bytes, median: 306 bytes). (Note: measurements were conducted in Python and therefore may introduce some overhead.)

Aside from zstd level 3 dictionary compression, Zstandard is faster than zlib level 6 across the board (I suspect this one-off is an oddity with the zstd compression parameters at this level and this corpus because zstd level 4 is faster than level 3, which is weird).

It's also worth noting that non-dictionary zstandard compression has similar compression ratios to zlib. Again, this demonstrates the intrinsic difficulties of compressing small inputs.

But the real takeaway from this data are the speed differences with dictionary compression enabled. Dictionary decompression is 2.2-2.4x faster than non-dictionary decompression. Already respectable ~240 MB/s decompression speed (measured at the output end) becomes ~530 MB/s. Zlib level 6 was ~140 MB/s, so swapping in dictionary compression makes things ~3.8x faster. It takes ~1.5s of CPU time to zlib decompress this corpus. So if Mercurial can be taught to use Zstandard dictionary compression for changelog data, certain operations on this corpus will complete ~1.1s faster. That's significant.

It's worth stating that Zstandard isn't the only compression algorithm or library to support dictionary compression. Brotli and zlib do as well, for example. But, Zstandard's support for dictionary compression seems to be more polished than other libraries I've seen. It has multiple APIs for training dictionaries from sample data. (Brotli has none nor does brotli's documentation say how to generate dictionaries as far as I can tell.)

Dictionary compression is definitely an advanced feature, applicable only to certain use cases (lots of small, similar data). But there's no denying that if you can take advantage of dictionary compression, you may be rewarded with significant performance wins.

A Versatile C API

I spend a lot of my time these days in higher-level programming languages like Python and JavaScript. By the time you interact with compression in high-level languages, the low-level compression APIs provided by the compression library are most likely hidden from you and bundled in a nice, friendly abstraction, suitable for a higher-level language. And more often than not, many features of that low-level API are not exposed for you to call. So, you don't get an appreciation for how good (or bad) or feature rich (or lacking) the low-level API is.

As part of writingpython-zstandard, I've spent a lot of time interfacing with the zstd C API. And, as part of evaluating other compression libraries for use in Mercurial, I've been looking at C APIs for other libraries and the Python bindings to them. A takeaway from this is an appreciation for the quality of zstd's C API.

Many compression library APIs are either too simple or too complex. Zstandard's is in the Goldilocks zone. Aside from a few minor missing features, its C API was more than adequate in its 1.0 release.

What I really appreciate about the zstd C API is that it provides high, medium, and low-level APIs. From the highest level, you throw it pointers to input and output buffers and it does an operation. From the medium level, you use a reusable context holding state and other parameters and it does an operation. From the low-level, you are calling multiple functions and shuffling bytes around, maintaining your own state and potentially bypassing the Zstandardframing format in the process. The different levels give you almost total control over everything. This is critical for performance optimization and when writing bindings for higher-level languages that may have different expectations on the behavior of software. The performance I've achieved in python-zstandard just isn't (easily) possible with other compression libraries because of their lacking API design.

Oftentimes when interacting with a C library I think if only there were a function to let me do X my life would be much easier. I rarely have this experience with Zstandard. The C API is well thought out, has almost all the features I want/need, and is pretty easy to use. While most won't notice this difference, it should be a significant advantage for Zstandard in the long run, as more bindings are written and more people have a high-quality experience with it because the C API allows them to.

Zstandard Isn't Perfect

I've been pretty positive about Zstandard so far in this post. In fear of sounding like a fanboy who is so blinded by admiration that he can't see faults and because nothing is perfect, I need to point out some negatives about Zstandard. (Aside: put little faith in the words uttered by someone who can't find a fault in something they praise.)

First, the framing format is a bit heavyweight in some scenarios. The frame header is at least 6 bytes. For input of 256-65791 bytes, recording the original source size and its checksum will result in a 12 byte frame. Zlib, by contrast, is only 6 bytes for this scenario. When storing tens of thousands of compressed records (this is a use case in Mercurial), the frame overhead can matter and this can make it difficult for compressed Zstandard data to be as small as zlib for very small inputs. (It's worth noting that zlib doesn't store the decompressed size in its header. There are pros and cons to this, which I'll discuss in my eventual post about python-zstandard and how it achieves optimal performance.) If the frame overhead matters to you, the zstd C API does expose a block API that operates at a level below the framing format, allowing you to roll your own framing protocol. I alsofiled a GitHub issue to make the 4 byte magic number optional, which would go a long way to cutting down on frame overhead.

Second, the C API is not yet fully stabilized. There are a number of functions marked as experimental that aren't exported from the shared library and are only available via static linking. There's a ton of useful functionality in there, including low-level compression parameter adjustment, digested dictionaries (for reusing computed dictionaries across multiple contexts), and the multi-threaded compression API. python-zstandard makes heavy use of these experimental APIs. This requires bundling zstd with python-zstandard and statically linking with this known version because functionality could change at any time. This is a bit annoying, especially for distro packagers.

Third, the low-level compression parameters are under-documented. I think I understand what a lot of them do. But it isn't obvious when I should consider adjusting what. The default compression levels seem to work pretty well and map to reasonable compression parameters. But a few times I've noticed that tweaking things slightly can result in desirable improvements. I wish there were a guide of sorts to help you tune these parameters.

Fourth, dictionary compression is still a bit too complicated and hand-wavy for my liking. I can measure obvious benefits when using it largely out of the box with some corpora. But it isn't always a win and the cost for training dictionaries is too high to justify using it outside of scenarios where you are pretty sure it will be beneficial. When I do use it, I'm not sure which compression levels it works best with, how many samples need to be fed into the dictionary trainer, which training algorithm to use, etc. If that isn't enough, there is also the concept of content-only dictionaries where you use a fulltext as the dictionary. This can be useful for delta-encoding schemes (where compression effectively acts like a diff/delta generator instead of using something like Myers diff). If this topic interests you, there is athread on the Mercurial developers list where Yann Collet and I discuss this.

Fifth and finally, Zstandard is still relatively new. I can totally relate to holding off until something new and shiny proves itself. That being said, the Zstandard framing protocol has some escape hatches for future needs. And, the project proved during its pre-1.0 days that it knows how to handle backwards and future compatibility issues. And considering Facebook and others are using Zstandard in production, I wouldn't be too worried. I think the biggest risk is to people (like me) who are writing code against the experimental C APIs. But even then, the changes to the experimental APIs in the past several months have been minor. I'm not losing sleep over it.

That may seem like a long and concerning list. But I think the issues are relatively minor. From my perspective, the biggest thing Zstandard has going against it is its youth. But that will only improve with age. While I'm usually pretty conservative about adopting new technology (I've gotten burned enough times that I prefer the neophytes do the field testing for me), the upside to using Zstandard is potentially drastic performance and efficiency gains. And that can translate to success versus failure or millions of dollars in saved infrastructure costs and productivity gains. I'm willing to take my chances.

Conclusion

For the corpora I've thrown at it, Zstandard handily outperforms zlib in almost every dimension. And, it even manages to best other modern compression algorithms like brotli in many tests.

The underlying algorithm and techniques used by Zstandard are highly parameterized, lending themselves to a variety of use cases from embedded hardware to massive data crunching machines with hundreds of gigabytes of memory and dozens of CPU cores.

The C API is well-designed and facilitates high performance and adaptability to numerous use cases. It is batteries included, providing functions to train dictionaries and perform multi-threaded compression.

Zstandard is backed by Facebook and seems to have a healthy open source culture on Github. My interactions with Yann Collet have been positive and he seems to be a great project maintainer.

Zstandard is an exciting advancement for data compression and therefore for the entire computing field. As someone who has lived in the world of zlib for years, was a casual user of compression, and thought zlib was good enough for most use cases, I can attest that Zstandard is game changing. After being enlightened to all the advantages of Zstandard, I'll never casually use zlib again: it's just too slow and inflexible for the needs of modern computing. If you use compression, I highly recommend investigating Zstandard.