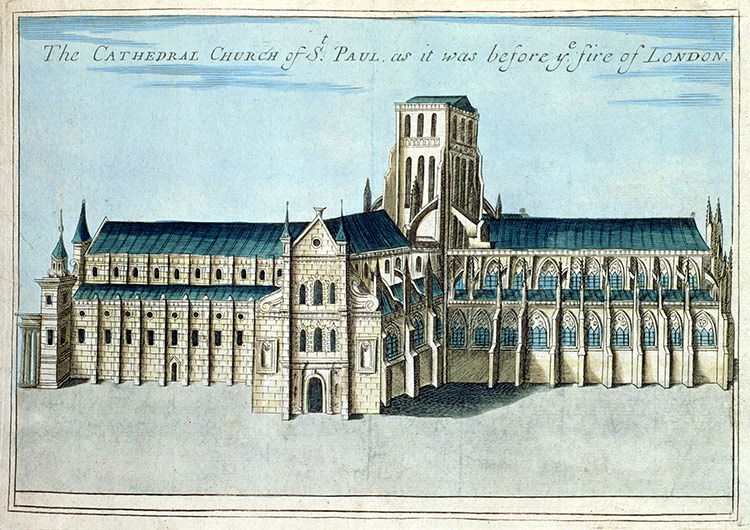

Early in the morning of Monday December 4th, 1514, an assistant gaoler named Peter Turner entered the cathedral close of the old St Paul’s. He was to attend to the one inmate then held in Lollards Tower, the Bishop of London’s prison, which adjoined the cathedral. In the company of two church officials, Turner ascended the winding stone staircase and unlocked the cell door. There he found the prisoner hanging by his own belt with his face to the wall.

The body was that of Richard Hunne, a liveryman of the Merchant Taylors Company, a prosperous London citizen, highly respected within his community and among his fellow tradesmen. His death while in the custody of the bishop, Richard Fitzjames, spread alarm among the London populace, where anti-clerical feelings were already running high. There were rumours of foul play but the Church authorities insisted that Hunne had committed suicide (felo de se) and in order to lay the matter to rest the bishop decided to try Hunne’s corpse on a charge of heresy.

The trial was held over several days in the week beginning December 11th. Witnesses were called and the prize exhibit displayed for all to see was Hunne’s Wycliffe Bible, with its notorious prologue that cast doubt on the miracle of the sacrament of the altar. On Saturday December 16th Fitzjames pronounced a verdict of guilty against the body of Hunne and a mandate requesting the Crown to implement punishment was dispatched to Westminster Palace. On December 20th the remains of the convicted man were carried to Smithfield and consigned to the flames.

However, the furore unleashed by Hunne’s suspicious death would not die down. The Lord Mayor, George Monoux, had instructed the coroner to empanel a jury to investigate the cause of death and 24 citizens from local wards were duly sworn in. After examining the body in situ and receiving evidence from witnesses, including a confession from one Charles Joseph, a church official in the employ of the Bishop’s Chancellor, Dr Horsey, they concluded that Hunne had been murdered and the body hung up to look like suicide. The alleged perpetrators were Horsey, Joseph and the prison gaoler, John Spalding, against whom indictments were issued. But there was a further unspoken implication: that none other than the Bishop of London, Fitzjames, had been the prime mover in the murder of Hunne.

So great was the threat to the church’s reputation that Fitzjames appealed to Thomas Wolsey, the newly appointed Archbishop of York, to halt legal proceedings against his chancellor and have the case examined by independent councillors. Henry VIII became involved and called a series of conferences to discuss the case and the wider issues of clerical privilege and the jurisdiction of church courts. The final conference at Baynard’s Castle was attended by councillors, judges, bishops and Members of Parliament and presided over by the king.

A compromise was eventually reached, whereby Horsey submitted himself before the Court of King’s Bench on a charge of murder. By acknowledging the authority of the royal courts, the Church opened the way for the king to instruct his Attorney General to accept Horsey’s plea of ‘not guilty’ and to dismiss the case against all three accused. Horsey was then removed from London to Exeter, where he lived out his years in exile.

A compromise was eventually reached, whereby Horsey submitted himself before the Court of King’s Bench on a charge of murder. By acknowledging the authority of the royal courts, the Church opened the way for the king to instruct his Attorney General to accept Horsey’s plea of ‘not guilty’ and to dismiss the case against all three accused. Horsey was then removed from London to Exeter, where he lived out his years in exile.

Hunne’s clash with the Church authorities had begun in 1511 with the death of his five-week-old son, Stephen. When he took the corpse for burial to St Mary Matfellon in Whitechapel, the parson, Thomas Dryfield, demanded as his traditional mortuary fee the most valuable possession of the deceased, in this case the infant’s christening robe. Hunne refused to comply with the request, arguing that a deceased infant could own nothing and that the robe was rightfully his father’s property.

On April 26th, 1512 Hunne was cited before the Archbishop’s Court of Audience in Lambeth. This was was presided over by the future Bishop of London Cuthbert Tunstall, who upheld Dryfield’s claim and required Hunne either to surrender his dead son’s gown or else to pay its estimated value of six shillings and eightpence, roughly equivalent to ten times the daily wage of a skilled artisan.

Hunne remained obdurate. On December 27th, 1512 he and some friends attended the church of St Mary Matfellon to celebrate the feast of St John the Evangelist, December 27th. The service was being conducted by parson Dryfield’s chaplain, Henry Marshall, and when the chaplain saw Hunne he denounced him, stopped the service and refused to continue until Hunne and his party had left, which they did. However, Hunne immediately brought an action for slander against Marshall in the Court of King’s Bench.

The suit was heard on January 25th, 1513, but then adjourned until April. It was at this point that Hunne brought into play his heavy artillery: a writ of praemunire that cited as co-defendants, Dryfield, his chaplain, Marshall, and Joseph. Tunstall, though not named, would also be implicated if the suit progressed. To issue a writ of praemunire was daring enough but to target the archbishop’s own judicial representative was breathtaking in its effrontery.

The Great Act of Praemunire had been put on the statute book in the reign of Richard II (r.1377-99). Its original purpose was to restrict the Pope’s jurisdiction in England. More recently it had been invoked to challenge the right of ecclesiastical courts to hear cases that should more properly be heard by the royal courts.

***

The case was first heard in the court of King’s Bench at Westminster Hall in the spring of 1513. Both this suit and the slander case were repeatedly adjourned until after Hunne’s death, so that the legal questions raised remained undecided.

In October 1514 Hunne was arrested on suspicion of heresy and imprisoned in Lollards Tower. On Saturday December 2nd he was taken upriver to Fitzjames’ country residence, Fulham Palace, and there examined by the bishop in his chapel. He was required to answer to a number of charges, including his reported objection to the payment of tithes and his support for the views of a neighbour, Joan Baker, who had been found guilty of heresy. At the end of his examination Hunne did not recant by signing a declaration nor did he admit the charges against him. He did however acknowledge in his own writing that he had spoken inadvisedly and submitted himself to his lord’s charitable and favourable correction. After this inconclusive hearing Hunne was taken back to Lollards Tower, where he was found hanging on the Monday morning.

It was obvious to the jurymen, when they examined the corpse hanging in Lollards Tower, that Hunne could not have killed himself. The noose was too small to accommodate the head; marks on his wrists showed that his hands had been tied; the serrations round the neck had been caused by some metal object and not by a silken belt; the body was clean (‘without any drivelling or splurging in any place of his body’), which was inconsistent with death by hanging; and the chair from which Hunne would have had to jump was too precariously placed on the bed to allow anybody to stand on it. There was a lot of blood lying in one corner of the cell and on the left side of Hunne’s discarded jacket there were two great streams of blood. Yet the face, doublet, collar and shirt of the corpse were clear, except for a couple of drops of blood from each nostril. Furthermore, a candle that on the Sunday night had been left burning on top of the stocks had been snuffed out, even though it was seven or eight feet from the body.

It was obvious to the jurymen, when they examined the corpse hanging in Lollards Tower, that Hunne could not have killed himself. The noose was too small to accommodate the head; marks on his wrists showed that his hands had been tied; the serrations round the neck had been caused by some metal object and not by a silken belt; the body was clean (‘without any drivelling or splurging in any place of his body’), which was inconsistent with death by hanging; and the chair from which Hunne would have had to jump was too precariously placed on the bed to allow anybody to stand on it. There was a lot of blood lying in one corner of the cell and on the left side of Hunne’s discarded jacket there were two great streams of blood. Yet the face, doublet, collar and shirt of the corpse were clear, except for a couple of drops of blood from each nostril. Furthermore, a candle that on the Sunday night had been left burning on top of the stocks had been snuffed out, even though it was seven or eight feet from the body.

The jury were struck by one other curious aspect of the corpse: ‘his head [was] fair combed, and his bonnet right sitting upon his head, with his eyes and mouth fair closed, without any staring, gaping or frowning.’ Evidently the body had been touched up.

It seemed clear to the jury that, if Hunne had not killed himself, he must have been murdered and the murder scene arranged to give the appearance of suicide:

Whereby it appeareth plainly to us all that the neck of Hunne was broken, and the great plenty of blood was shed before he was hanged. Wherefore all we find, by God and all our consciences, that Richard Hunne was murdered. Also we acquit the said Richard Hunne of his own death.

The question for the jury then was who murdered Hunne? The answer appeared to be straightforward, because Joseph made the following confession while being held in the Tower of London:

Also Charles Joseph saith that, when Richard Hunne was slain, John Bellringer [Spalding] bare up the stairs into the Lollard’s Tower a wax candle, having the keys of the doors hanging on his arm. And I, Charles, went next to him, and Master Chancellor came up last. And when all we came up, we found Hunne lying on his bed. And then Master Chancellor said, Lay hands on the thief! And so we all three murdered Hunne. And then I, Charles, put the girdle about Hunne’s neck. And then John Bellringer and I, Charles, did heave up Hunne, and Master Chancellor pulled the girdle over the staple. And so Hunne was hanged.

Relying mainly on Joseph’s testimony, the jury in their final verdict concluded that Horsey, Joseph and Spalding, otherwise known as John Bellringer, had indeed broken the neck of Hunne and hung him up by his own girdle.

***

The view favoured by contemporary opinion and by most modern historians – that Hunne was murdered by church officials – appears persuasive. But the key question is this: why on earth would the Church authorities wish to kill him? First, it appears that the praemunire suit, to be heard in the January term of the court of King’s Bench, was about to fail. If true, Hunne’s untimely death deprived the church of its victory. Second, Bishop Fitzjames and his chancellor already had Hunne in their power because there was enough available evidence against him to secure a conviction on a charge of heresy. Again, the church was robbed of its prey. As Thomas More later pointed out, Horsey had no need to commit murder when he was already in a position to bring Hunne ‘to shame and peradventure to shameful death also’.

Indeed, the testimony of witnesses indicates that the chancellor was concerned that Hunne might be tempted to commit suicide after his examination at Fulham. Far from wishing Hunne dead, he took precautions against any attempt at self-harm because he wanted his prisoner kept alive. On the Sunday preceding Hunne’s death Turner, the junior gaoler, was for the first time locked into the prison cell while the inmate ate his dinner and, as a further safeguard, Spalding, when put in charge of the prisoner that same afternoon, was instructed by the chancellor to bring him neither ‘shirt, cap, kerchief or any other thing but that I see it before it come to him’.

Why did the bishop and his chancellor want to keep Hunne alive? Surely it was because they believed that Hunne had powerful confederates. Certainly, the merchant taylor was comfortably off, possessing tenements and other property that may have amounted to some £600. But what man, especially a man of business, would sink his wealth into costly – and dangerous – legal actions against the Church? There was not one suit but three, of which the libel and praemunire cases were adjourned time and again, no doubt at great cost to the plaintiff. The expense of attorneys, pleadings, writs and other legal fees over several years must have been a heavy burden even for someone in Hunne’s position. Was it credible that a man with a young family and the ambition to expand his business would pour his money away in such a manner?

A clue to the church’s suspicions on this score is provided in the testimony of Joseph’s servant, Julian Littel. According to him, Joseph complained that were it not for Hunne’s death ‘I could bring my Lord of London [Fitzjames] to the doors of heretics in London, both of men and women, that be worth £1,000’. At another time he said that he had in mind as potential suspects ‘the best in London’. From this it seems that Joseph had been led to believe that Hunne could be made to expose heretics in high places, which would offer the prospect of hefty summoner’s fees.

***

All this supports the view that Fitzjames and his chancellor wanted Hunne alive so that he could be interrogated about his supposed confederates and backers. But if Hunne did not commit suicide, as the coroner’s jury proved beyond doubt he could not, and if he was not murdered by Horsey and his junior officials, as seems totally improbable, what happened in Lollards Tower that fateful night?

To answer that question it is necessary to look closely at the canon law of torture. The single most important document on the subject of judicial torture by the church is the decree Ad Extirpanda issued by Pope Innocent IV in 1252:

In addition, the official or rector should obtain from all heretics he has captured a confession by force without injuring the body or causing the danger of death, for they are indeed thieves and murderers of souls and apostates from the sacraments of God and of the Christian faith. They should confess to their own errors and accuse other heretics whom they know, as well as their accomplices, fellow-believers, receivers, and defenders, just as rogues and thieves [fures et latrones] of worldly goods are made to accuse their accomplices and confess the evils which they had committed.

Ad Extirpanda therefore permitted the introduction of torture into the process of investigating heretics, particularly where the objective was to identify the accused’s accomplices. The significance of the language of Ad Extirpanda becomes apparent when viewed in the light of the words used by Joseph in his confession:

And when all we came up, we found Hunne lying on his bed. And then Master Chancellor said, Lay hands on the thief!

The curious characterisation of the suspect heretic as a ‘thief’ has caused puzzlement among some commentators. But, if Horsey was intending to torture Hunne in accordance with the papal decree Ad Extirpanda, the word thief would be entirely apt and fitting. Indeed, the language used here provides a crucial clue to what really happened in Lollards Tower.

Once it is recognised that Horsey and his two church officers were intent on torturing Hunne, much else falls into place, especially if reference is made to the relevant canon law. After the papal promulgation of 1252 the medieval canon lawyers and jurists developed a richly documented jurisprudence of judicial torture with its own rules, treatises and learned doctors of law. Many of the rules were designed to limit the obvious abuses to which indiscriminate torture could give rise and to protect the rights of the accused.

First and foremost torture, being a last resort, can only be used if the truth of the facts cannot be otherwise elicited. This means that if the accused has already confessed or if sufficient credible witnesses have already proved his guilt he cannot then be tortured. Second, there must be ‘half-proof’ against the accused or what we would call probable cause before resort can be had to duress.

If these basic principles are applied to the judicial proceedings against Hunne they are found to fit exactly. Hunne was subjected to a preliminary examination in Fulham, where sufficient evidence was produced by his bishop to establish a strong prima facie case against him on a charge of heresy. However, full proof supported by witnesses was not offered. Furthermore, while Hunne submitted himself to his bishop’s correction, thereby conceding the strength of the charges he faced, he made no formal signed confession of his guilt. Here then were the precise circumstances in which torture could be justified in canon law.

Other canonical rules are also significant. The interrogating judge (in this case Horsey) must not administer torture by his own hands but through junior officials (generally two). Hence the need for the presence of three men in Lollards Tower; one to preside as judge, another to hold down the accused and the third to administer the torture (Joseph’s role). The torture should not take place on a feast day such as Sunday: Hunne’s ordeal began just after midnight on the Monday morning. Furthermore, the accused must fast for nine or ten hours before torture; hence Horsey’s command on the Sunday, to the effect that Hunne should have no supper that night:

And after dinner, when the Bellringer fetched out the boy [Turner] the Bellringer said to the same boy Come no more hither with meat for him [Hunne] until tomorrow at noon, for Master Chancellor hath commanded that he shall have but one meal a day.

Finally, according to jurists, the accused should also be warned beforehand of the torture that is planned for him. This would account for an incident that is recorded in the coroner’s report:

Moreover, it is well proved that before Hunne’s death the said chancellor came up into the said Lollards Tower and kneeled down before Hunne, holding up his hands to him, praying him of forgiveness for all that he had done to him, and must do to him.

The circumstantial detail points overwhelmingly to a plan to torture Hunne that went horribly wrong. But how can one reconcile this with Joseph’s apparent confession to murder, made first to his servant, Littel, and later, when under interrogation in the Tower of London. Littel gave testimony as follows:

Then Charles [Joseph] said to Julian I have destroyed Richard Hunne! Alas, Master, said Julian. How? He was called a honest man! Charles answered, I put a wire in his nose!

There are two interesting points to be made about this testimony of Joseph’s servant. First of all, Joseph was not reported to have said that he intended to kill Hunne, only that he had done so by putting a wire up his nose. Second, Littel’s statement shows that Joseph was extremely upset over the killing: he was reported as saying that he would forego £100, if what had happened could be undone. He went on to complain that Hunne’s death had deprived him of the opportunity to turn in other wealthy persons suspected of heresy. For Joseph, Hunne’s death was a disaster.

Fitzjames accused Joseph of making a false confession in the Tower. But why would his summoner falsely admit to (joint) murder rather than to administering a form of torture that went wrong? The answer, surely, is simple. Under canon law someone who tortures an accused party may be held guilty of a capital offence if the victim dies as a consequence. The Church could also be expected to close ranks against the man who directly implemented the torture. On the other hand, by claiming that he and the bishop’s chancellor jointly murdered Hunne he would bring himself under the protection of the Church. After all, the Church authorities could not allow the bishop’s deputy to be convicted of a murder that would cast suspicion on the Bishop of London himself.

***

It is now possible to reconstruct the events that led up to the death of Hunne. Bishop Fitzjames and his chancellor became convinced that Hunne’s apparently single-handed legal assault on the Church was actively backed by other significant figures in the City. They therefore decided to extract from their prisoner, under duress, the identity of his confederates. After Horsey’s expertise in canon law had been called upon, it was decided to establish a prima facie case against the suspect heretic during a preliminary examination in Fulham. But Hunne was not permitted to sign a formal confession because this would undermine the canonical case for torture.

On Sunday December 3rd Horsey, having kneeled before Hunne and prayed forgiveness for what he must do to him, made sure that his prisoner fasted after his midday meal. Because Hunne would by now be aware that something unpleasant was in store, he was subjected to a regime that might today be described as a suicide watch. That evening he was left lying on his bed with his hands bound. Shortly after midnight Joseph and Spalding met up with Horsey and the three of them climbed the stairs of Lollards Tower, their way lit by a single candle. On entering the cell Horsey proclaimed the papal authority for his actions by calling out (in English, for the benefit of his collaborators) ‘Lay hands on the thief’. It was then an easy matter for Joseph to heat a wire in the candle flame and insert it into Hunne’s nose.

The three conspirators would have been unaware of elementary medical facts about the circulation of blood and the presence of blood vessels in the upper nasal passages. They must therefore have been shocked when Hunne experienced a catastrophic posterior nasal haemorrhage, the more so as they found themselves powerless to staunch the resulting flow of blood (the tell-tale evidence of this haemorrhage in the hanging corpse was the presence of small streams of blood from both nostrils.) In his weakened condition Hunne, it may be surmised, died of loss of blood: much of it pouring over his clothes and the cell floor but a great deal also being absorbed down his throat. The trauma would be even greater if the wire had pierced the cribriform plate located between the upper nasal passages and the brain. It would probably have taken some time for Hunne to die and the conspirators must have been in a state of panic.

The extent of that panic is difficult to exaggerate. To spill blood was a grave canonical sin but to kill a man under torture was unpardonable. It would also be a public relations disaster for the Church, if the truth ever got out. The decision was therefore taken to clear up the blood (some of it missed in the dim candlelight), break Hunne’s neck and then hang him up by his own belt to make it look like suicide. As a final gesture of remorse the conspirators combed the victim’s hair, placed his cap neatly on his head and closed his eyes. They knew they had done him a great wrong and, in a macabre acknowledgement of their fault, they gave Hunne in death a degree of dignity that they had denied him in life.

Richard Dale is an economist and barrister who was recently elected a fellow of the Royal Historical Society.