In April of 1988, Brian Moriarty of Infocom flew from the East Coast to the West to attend the first ever Computer Game Developers Conference. Hard-pressed from below by the slowing sales of their text adventures and from above by parent company Activision’s ever more demanding management, Infocom didn’t have the money to pay for Moriarty’s trip. Thus he went on his own dime, a situation which left him, as he would later put it, very “grumpy” about the prospect of his ongoing employment by the very company at which he had worked so desperately to win a spot just a few years before.

In time, the Computer Game Developers Conference would evolve into simply the Game Developers Conference, one of the biggest events on the calendar of a $30 billion industry. In 1988, however, it consisted of 26 people stuffed into the San Jose living room of Chris Crawford, the conference’s founder and organizer. Moriarty recalls showing up a little late, scanning the room, and seeing just one chair free, oddly on the first row. He rushed over to take it, and soon struck up a conversation with the man sitting next to him, whom he had never met before that day. As fate would have it, his neighbor’s name was Noah Falstein, and he worked for Lucasfilm Games.

Attendees to the first ever Computer Game Developers Conference. Brian Moriarty is in the reddish tee-shirt at center rear, looking cool in his rock-star shades.

Falstein knew and admired Moriarty’s work for Infocom, and knew likewise, as did everyone in the industry, that things hadn’t been going so well back in Cambridge for some time now. His own Lucasfilm Games was in the opposite position. After having struggled since their founding back in 1982 to carve out an identity for themselves under the shadow of George Lucas’s Star Wars empire, by 1988 they finally had the feeling of a company on the rise. With Maniac Mansion, their big hit of the previous year, Falstein and his colleagues seemed to have found in point-and-click graphical adventures a niche that was both artistically satisfying and commercially rewarding. They were already hard at work on the follow-up to Maniac Mansion, and Lucasfilm Games’s management had given the go-ahead to look for an experienced adventure-game designer to help them make more games. As one of Infocom’s most respected designers, Brian Moriarty made an immediately appealing candidate, not least in that Lucasfilm Games liked to see themselves as the Infocom of graphical adventures, emphasizing craftsmanship and design as a way to set themselves apart from the more slapdash games being pumped out in much greater numbers by their arch-rivals Sierra.

For his part, Moriarty was ripe to be convinced; it wasn’t hard to see the writing on the wall back at Infocom. When Falstein showed him some photographs of Lucasfilm Games’s offices at Skywalker Ranch in beautiful Marin County, California, and shared stories of rubbing elbows with movie stars and casually playing with real props from the Star Wars and Indiana Jones movies, the contrast with life inside Infocom’s increasingly empty, increasingly gloomy offices could hardly have been more striking. Then again, maybe it could have been: at his first interview with Lucasfilm Games’s head Steve Arnold, Moriarty was told that the division had just two mandates. One was “don’t lose money”; the other was “don’t embarrass George Lucas.” Anything else — like actually making money — was presumably gravy. Again, this was music to the ears of Moriarty, who like everyone at Infocom was now under constant pressure from Activision’s management to write games that would sell in huge numbers.

Brian Moriarty arrived at Skywalker Ranch for his first day of work on August 1, 1988. As Lucasfilm Games’s new star designer, he was given virtually complete freedom to make whatever game he wanted to make.

Noah Falstein in Skywalker Ranch’s conservatory. This is where the Games people typically ate their lunches, which were prepared for them by a gourmet chef. There were definitely worse places to work…

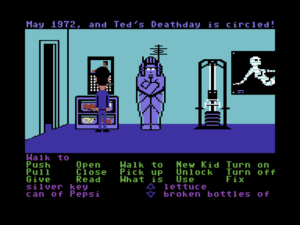

For all their enthusiasm for adventure games, the other designers at Lucasfilm were struggling a bit at the time to figure out how to build on the template of Maniac Mansion. Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders, David Fox’s follow-up to Ron Gilbert’s masterstroke, had been published just the day before Moriarty arrived at Skywalker Ranch. It tried a little too obviously to capture the same campy charm, whilst, in typical games-industry fashion, trying to make it all better by making it bigger, expanding the scene of the action from a single night spent in a single mansion to locations scattered all around the globe and sometimes off it. The sense remained that Lucasfilm wanted to do things differently from Sierra, who are unnamed but ever-present — along with a sly dig at old-school rivals like Infocom still making text adventures — within a nascent manifesto of three paragraphs published in Zak McKracken‘s manual, entitled simply “Our Game Design Philosophy.”

We believe that you buy games to be entertained, not to be whacked over the head every time you make a mistake. So we don’t bring the game to a screeching halt when you poke your nose into a place you haven’t visited before. In fact, we make it downright difficult to get a character “killed.”

We think you’d prefer to solve the game’s mysteries by exploring and discovering. Not by dying a thousand deaths. We also think you like to spend your time involved in the story. Not typing in synonyms until you stumble upon the computer’s word for a certain object.

Unlike conventional computer adventures, Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders doesn’t force you to save your progress every few minutes. Instead, you’re free to concentrate on the puzzles, characters, and outrageous good humor.

Worthy though these sentiments were, Lucasfilm seemed uncertain as yet how to turn them into practical rules for design. Ironically, Zak McKracken, the game with which they began publicly articulating their focus on progressive design, is the most Sierra-like Lucasfilm game ever made, with the sheer nonlinear sprawl of the thing spawning inevitable confusion and yielding far more potential dead ends than its designer would likely wish to admit. While successful enough in its day, it never garnered the love that’s still accorded to Maniac Mansion today.

Lucasfilm Games’s one adventure of 1989 was a similarly middling effort. A joint design by Gilbert and Falstein, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: The Graphic Adventure— an Action Game was also made — marked the first time since Labyrinth that the games division had been entrusted with one of George Lucas’s cinematic properties. They don’t seem to have been all that excited at the prospect. The game dutifully walks you through the plot you’ve already watched unfold on the silver screen, without ever taking flight as a creative work in its own right. The Lucasfilm “Game Design Philosophy” appears once again in the manual in almost the exact same form as last time, but once again the actual game hews to this ideal imperfectly at best, with, perhaps unsurprisingly given the two-fisted action movie on which it’s based, lots of opportunities to get Indy killed and have to revert to one of those save files you supposedly don’t need to create.

So, the company was rather running to stand still as Brian Moriarty settled in. They were determined to evolve their adventure games in design terms to match the strides Sierra was making in technology, but were uncertain how to actually go about the task. Moriarty wanted to make his own first work for Lucasfilm a different, more somehow refined experience than even the likes of Maniac Mansion. But how to do so? In short, what should he do with his once-in-a-lifetime chance to make any game he wanted to make?

Flipping idly through a computer magazine one day, he was struck by an advertisement that prominently featured the word “loom.” He liked the sound of it; it reminded him of other portentous English words like “gloom”, “doom,” and “tomb.” And he liked the way it could serve as either a verb or a noun, each with a completely different meaning. In a fever of inspiration, he sat down and wrote out the basis of the adventure game he would soon design, about a Loom which binds together the fabric of reality, a Guild of Weavers which uses the Loom’s power to make magic out of sound, and Bobbin Threadbare, the “Loom Child” who must save the Loom — and thus the universe — from destruction before it’s too late. It would be a story and a game with the stark simplicity of fable.

Simplicity, however, wasn’t exactly trending in the computer-games industry of 1988. Since the premature end of the would-be Home Computer Revolution of the early 1980s, the audience for computer games had grown only very slowly. Publishers had continued to serve the same base of hardcore players, who lusted after ever more complex games to take advantage of the newest hardware. Simulations had collected ever more buttons and included ever more variables to keep track of, while strategy games had gotten ever larger and more time-consuming. Nor had adventure games been immune to the trend, as was attested by Moriarty’s own career to date. Each of his three games for Infocom had been bigger and more difficult than the previous, culminating in his adventure/CRPG hybrid Beyond Zork, the most baroque game Infocom had made to date, with more options for its onscreen display alone than some professional business applications. Certainly plenty of existing players loved all this complexity. But did all games really need to go this way? And, most interestingly, what about all those potential players who took one look at the likes of Beyond Zork and turned back to the television? Moriarty remembered a much-discussed data point that had emerged from the surveys Infocom used to send to their customers: the games people said were their favorites overlapped almost universally with those they said they had been able to finish. In keeping with this trend, Moriarty’s first game for Infocom, which had been designed as an introduction to interactive fiction for newcomers, had been by far his most successful. What, he now thought, if he used the newer hardware at his disposal in the way that Apple has historically done, in pursuit of simplicity rather than complexity?

Lucasfilm Games’s current point-and-click interface, while undoubtedly the most painless in the industry at the time, was nevertheless far too complicated for Moriarty’s taste, still to a large extent stuck in the mindset of being a graphical implementation of the traditional text-adventure interface rather than treating the graphical adventure as a new genre in its own right. Thus the player was expected to first select a verb from a list at the bottom of the screen and then an object to which to apply it. The interface had done the job well enough to date, but Moriarty felt that it would interfere with the seamless connection he wished to build between the player sitting there before the screen and the character of Bobbin Threadbare standing up there on the screen. He wanted something more immediate, more intuitive — preferably an interface that didn’t require words at all. He envisioned music as an important part of his game: the central puzzle-solving mechanic would involve the playing of “drafts,” little sequences of notes created with Bobbin’s distaff. But he wanted music to be more than a puzzle-solving mechanic. He wanted the player to be able to play the entire game like a musical instrument, wordlessly and beautifully. He was thus thrilled when he peeked under the hood of Lucasfilm’s SCUMM adventure-game engine and found that it was possible to strip the verb menu away entirely.

Some users of Apple’s revolutionary HyperCard system for the Macintosh were already experimenting with wordless interfaces. Within weeks of HyperCard’s debut, a little interactive storybook called Inigo Gets Out, “programmed” by a non-programmer named Amanda Goodenough, had begun making the rounds, causing a considerable stir among industry insiders. The story of a house cat’s brief escape to the outdoors, it filled the entire screen with its illustrations, responding intuitively to single clicks on the pictures. Just shortly before Moriarty started work at Lucasfilm Games, Rand and Robyn Miller had taken this experiment a step further with The Manhole, a richer take on the concept of an interactive children’s storybook. Still, neither of these HyperCard experiences quite qualified as a game, and Moriarty and Lucasfilm were in fact in the business of making adventure games. Loom could be simple, but it had to be more than a software toy. Moriarty’s challenge must be to find enough interactive possibility in a verb-less interface to meet that threshold.

In response to that challenge, Moriarty created an interface that stands out today as almost bizarrely ahead of its time; not until years later would its approach be adopted by graphic adventures in general as the default best way of doing things. Its central insight, which it shared with the aforementioned HyperCard storybooks, was the realization that the game didn’t always need the player to explicitly tell it what she wanted to do when she clicked a certain spot on the onscreen picture. Instead the game could divine the player’s intention for itself, based only on where she happened to be clicking. What was sacrificed in the disallowing of certain types of more complex puzzles was gained in the creation of a far more seamless, intuitive link between the player, the avatar she controlled, and the world shown on the screen.

The brief video snippet above shows Loom‘s user interface in its entirety. You make Bobbin walk around by clicking on the screen. Hovering the mouse over an object or character with which Bobbin can interact brings up an image of that object or character in the bottom right corner of the screen; double-clicking the same “hot spot” then causes Bobbin to engage, either by manipulating an object in some way or by talking to another character. Finally, Bobbin can cast “spells” in the form of drafts by clicking on the musical staff at the bottom of the screen. In the snippet above, the player learns the “open” draft by double-clicking on the egg, an action which in this case results in Bobbin simply listening to it. The player and Bobbin then immediately cast the same draft to reveal within the egg his old mentor, who has been transformed into a black swan.

Moriarty seemed determined to see how many of the accoutrements of traditional adventure games he could strip away and still have something that was identifiable as an adventure game. In addition to eliminating menus of verbs, he also excised the concept of an inventory; throughout the game, Bobbin carries around with him nothing more than the distaff he uses for weaving drafts. With no ability to use this object on that other object, the only puzzle-solving mechanic that’s left is the magic system. In the broad strokes, magic in Loom is very much in the spirit of Infocom’s Enchanter series, in which you collect spells for your spell book, then cast them to solve puzzles that, more often than not, reward you with yet more spells. In Loom the process is essentially the same, expect that you’re collecting musical drafts to weave on your distaff rather than spells for your spell book. And yet this musical approach to spell weaving is as lovely as a game mechanic can be. Lucasfilm thoughtfully included a “Book of Patterns” with the game, listing the drafts and providing musical staffs on which you can denote their sequences of notes as you discover them while playing.

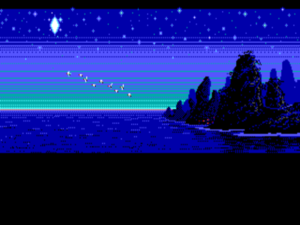

The audiovisual aspect of Loom was crucial to capturing the atmosphere of winsome melancholia Moriarty was striving for. Graphics and sound were brand new territory for him; his previous games had consisted of nothing but text. Fortunately, the team of artists that worked with him grasped right away what was needed. Each of the guilds of craftspeople which Bobbin visits over the course of the game is marked by its own color scheme: the striking emerald of the Guild of Glassmakers, the softer pastoral greens of the Guild of Shepherds, the Stygian reds of the Guild of Blacksmiths, and of course the lovely, saturated blues and purples of Bobbin’s own Guild of Weavers. This approach came in very handy for technical as well as thematic reasons, given that Loom was designed for EGA graphics of just 16 onscreen colors.

The overall look of Loom was hugely influenced by the 1959 Disney animated classic Sleeping Beauty, with many of the panoramic shots in the game dovetailing perfectly with scenes from the film. Like Sleeping Beauty, Loom was inspired and accompanied by the music of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, whom Moriarty describes as his “constant companion throughout my life”; while Sleeping Beauty draws from Tchaikovsky’s ballet of the same name, Loom draws from another of his ballets, Swan Lake. Loom sounds particularly gorgeous when played through a Roland MT-32 synthesizer board — an experience that, given the $600 price tag of the Roland, far too few players got to enjoy back in the day. But regardless of how one hears it, it’s hard to imagine Loom without its classical soundtrack. Harking back to Hollywood epics like 2001: A Space Odyssey, the MT-32 version of Loom opens with a mood-establishing orchestral overture over a blank screen.

To provide the final touch of atmosphere, Moriarty walked to the other side of Skywalker Ranch, to the large brick building housing Skywalker Sound, and asked the sound engineers in that most advanced audio-production facility in the world if they could help him out. Working from a script written by Moriarty and with a cast of voice actors on loan from the BBC, the folks at Skywalker Sound produced a thirty-minute “audio drama” setting the scene for the opening of the game; it was included in the box on a cassette. Other game developers had occasionally experimented with the same thing as a way of avoiding having to cover all that ground in the game proper, but Loom‘s scene-setter stood out for its length and for the professional sheen of its production. Working for Lucasfilm did have more than a few advantages.

If there’s something to complain about when it comes to Loom the work of interactive art, it must be that its portentous aesthetics lead one to expect a thematic profundity which the story never quite attains. Over the course of the game, Bobbin duly journeys through Moriarty’s fairy-tale world and defeats the villain who threatens to rip asunder the fabric of reality. The ending, however, is more ambiguous than happy, with only half of the old world saved from the Chaos that has poured in through the rip in the fabric. I don’t object in principle to the idea of a less than happy ending (something for which Moriarty was becoming known). Still, and while the final image is, like everything else in the game, lovely in its own right, this particular ambiguous ending feels weirdly abrupt. The game has such a flavor of fable or allegory that one somehow wants a little more from it at the end, something to carry away back to real life. But then again, beauty, which Loom possesses in spades, has a value of its own, and it’s uncertain whether the sequels Moriarty originally planned to make — Loom had been envisioned as a trilogy — would have enriched the story of the first game or merely, as so many sequels do, trampled it under their weight.

From the practical standpoint of a prospective purchaser of Loom upon its initial release, on the other hand, there’s room for complaint beyond quibbling about the ending. We’ve had occasion before to observe how the only viable model of commercial game distribution in the 1980s and early 1990s, as $40 boxed products shipped to physical store shelves, had a huge effect on the content of those games. Consumers, reasonably enough, expected a certain amount of play time for their $40. Adventure makers thus learned that they needed to pad out their games with enough puzzles — too often bad but time-consuming ones — to get their play times up into the region of at least twenty hours or so. Moriarty, however, bucked this trend in Loom. Determined to stay true to the spirit of minimalism to the bitter end, he put into the game only what needed to be there. The end result stands out from its peers for its aesthetic maturity, but it’s also a game that will take even the most methodical player no more than four or five hours to play. Today, when digital distribution has made it possible for developers to make games only as long as their designs ask to be and adjust the price accordingly, Loom‘s willingness to do what it came to do and exit the stage without further adieu is another quality that gives it a strikingly modern feel. But in the context of the times of the game’s creation, it was a bit of a problem.

When Loom was released in March of 1990, many hardcore adventure gamers were left nonplussed not only by the game’s short length but also by its simple puzzles and minimalist aesthetic approach in general, so at odds with the aesthetic maximalism that has always defined the games industry as a whole. Computer Gaming World‘s Johnny Wilson, one of the more sophisticated game commentators of the time, did get what Loom was doing, praising its atmosphere of “hope and idealism tainted by realism.” Others, though, didn’t seem quite so sure what to make of an adventure game that so clearly wanted its players to complete it, to the point of including a “practice” mode that would essentially solve all the puzzles for them if they so wished. Likewise, many players just didn’t seem equipped to appreciate Loom‘s lighter, subtler aesthetic touch. Computer Gaming World‘s regular adventure-gaming columnist Scorpia, a traditionalist to the core, said the story “should have been given an epic treatment, not watered down” — a terrible idea if you ask me (if there’s one thing the world of gaming, then or now, doesn’t need, it’s more “epic” stories). “As an adventure game,” she concluded, “it is just too lightweight.” Ken St. Andre, creator of Tunnels & Trolls and co-creator of Wasteland, expressed his unhappiness with the ambiguous ending in Questbusters, the ultimate magazine for the adventuring hardcore:

The story, which begins darkly, ends darkly as well. That’s fine in literature or the movies, and lends a certain artistic integrity to such efforts. In a game, however, it’s neither fair nor right. If I had really been playing Bobbin, not just watching him, I would have done some things differently, which would have netted a different conclusion.

Echoing as they do a similar debate unleashed by the tragic ending of Infocom’s Infidel back in 1983, the persistence of such sentiments must have been depressing for Brian Moriarty and others trying to advance the art of interactive storytelling. St. Andre’s complaint that Loom wouldn’t allow him to “do things differently” — elsewhere in his review he claims that Loom“is not a game” at all — is one that’s been repeated for decades by folks who believe that anything labeled as an interactive story must allow the player complete freedom to approach the plot in her own way and to change its outcome. I belong to the other camp: the camp that believes that letting the player inhabit the role of a character in a relatively fixed overarching narrative can foster engagement and immersion, even in some cases new understanding, by making her feel she is truly walking in someone else’s shoes — something that’s difficult to accomplish in a non-interactive medium.

Responses like those of Scorpia and Ken St. Andre hadn’t gone unanticipated within Lucasfilm Games prior to Loom‘s release. On the contrary, there had been some concern about how Loom would be received. Moriarty had countered by noting that there were far, far more people out there who weren’t hardcore gamers like those two, who weren’t possessed of a set of fixed expectations about what an adventure game should be, and that many of these people might actually be better equipped to appreciate Loom‘s delicate aesthetics than the hardcore crowd. But the problem, the nut nobody would ever quite crack, would always be that of reaching this potential alternate customer base. Non-gamers didn’t read the gaming magazines where they might learn about something like Loom, and even Lucasfilm Games wasn’t in a position to launch a major assault on the alternative forms of media they did peruse.

In the end, Loom wasn’t a flop, and thus didn’t violate Steve Arnold’s dictum of “don’t lose money” — and certainly it didn’t fall afoul of the dictum of “don’t embarrass George.” But it wasn’t a big hit either, and the sequels Moriarty had anticipated for better or for worse never got made. Ron Gilbert’s The Secret of Monkey Island, Lucasfilm’s other adventure game of 1990, was in its own way as brilliant as Moriarty’s game, but was much more traditional in its design and aesthetics, and wound up rather stealing Loom‘s thunder. It would be Monkey Island rather than Loom that would become the template for Lucasfilm’s adventure games going forward. Lucasfilm would largely stick to comedy from here on out, and would never attempt anything quite so outré as Loom again. It would only be in later years that Moriarty’s game would come to be widely recognized as one of Lucasfilm Games’s finest achievements. Such are the frustrations of the creative life.

Having made Loom, Brian Moriarty now had four adventure games on his CV, three of which I consider to be unassailable classics — and, it should be noted, the fourth does have its fans as well. He seemed poised to remain a leading light in his creative field for a long, long time to come. It therefore feels like a minor tragedy that this his first game for Lucasfilm would mark the end of his career in adventure games rather than a new beginning; he would never again be credited as the designer of a completed adventure game. We’ll have occasion to dig a little more into the reasons why that should have been the case in a future article, but for now I’ll just note how much an industry full of so many blunt instruments could have used his continuing delicate touch. We can only console ourselves with the knowledge that, should Loom indeed prove to be the last we ever hear from him as an adventure-game designer, it was one hell of a swansong.

(Sources: the book Game Design Theory and Practice by Richard Rouse III; ACE of April 1990; Questbusters of June 1990 and July 1990; Computer Gaming World of April 1990 and July/August 1990. But the bulk of this article was drawn from Brian Moriarty’s own Loom postmortem for, appropriately enough, the 2015 Game Developers Conference, which was a far more elaborate affair than the 1988 edition.

Loom is available for purchase is from GOG.com. Sadly, however, this is the VGA/CD-ROM re-release — I actually prefer the starker appearance of the original EGA graphics — and lacks the scene-setting audio drama. It’s also afflicted with terrible voice acting which completely spoils the atmosphere, and the text is bowdlerized to boot. Motivated readers should be able to find both the original version and the audio drama elsewhere on the Internet without too many problems. I do recommend that you seek them out, perhaps after purchasing a legitimate copy to fulfill your ethical obligation, but I can’t take the risk of hosting them here.)