Recipe books from the Middle Ages reveal the extreme methods with which artists achieved their reds.

For the most part, painters have always loved red, from the Paleolithic period to the most contemporary. Very early on, red’s palette came to offer a variety of shades and to favor more diverse and subtle chromatic play than any other color. In red, artists found a means to construct pictorial space, distinguish areas and planes, create accents, produce effects of rhythm and movement, and highlight one figure or another. On walls, canvas, wood, or parchment, the música of reds was always more pregnant, more cadenced, and more resonant than others. Moreover, painting treatises and manuals are not mistaken; it is always with regard to red that they are most long-winded and offer the greatest number of recipes. For a long time, it was also the chapter on reds that began the exposition on pigments useful to painters. That was already the case in Pliny’s Natural History, which had more to say on red than on any other color. And the same is true for the collections of the medieval recipes intended for illuminators and in the treatises on painting printed in Venice in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It was not until the century of the Enlightenment that in certain works—most often written by art theoreticians and not painters themselves—the chapter on blues would precede the one on reds and offer a greater number of suggestions.

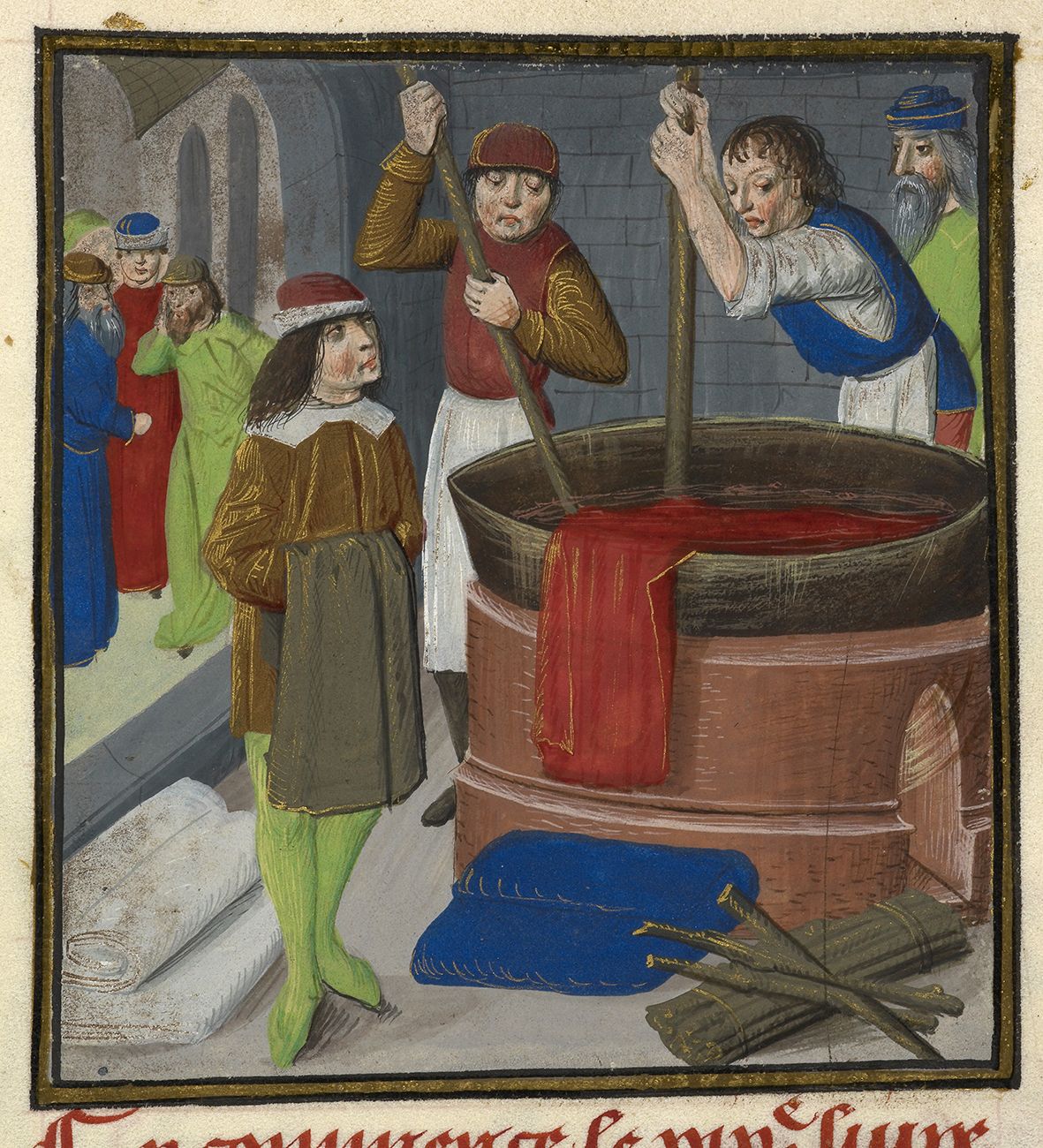

For now, let us open those recipe collections from the end of the Middle Ages, called réceptaires by scholars. These are difficult documents to date or study, not only because they were all copied by hand, each new copy offering a new account of the text, adding or omitting recipes, altering others, changing a product’s name or designating different products by the same name, but also because practical advice and methods continually appear side by side with allegorical or symbolic considerations. The same sentence may contain obscure annotations on the symbolism of colors and practical recommendations on ways to fill a mortar or clean a container. Moreover, notes on quantity and proportion are often imprecise, and cooking, decoction, or maceration times are rarely indicated. As was often the case in the Middle Ages, the ritual seems more important than the results, and numbers, when they are given, seem to have more to do with qualities than quantities. The wording is sometimes surprising. A recipe from Lombardy from the 1400s intended for illuminators begins with this sentence: “If you want to make a bit of good red paint, take an ox … ” Surely the author is having fun here when he calls for an entire animal of enormous size to transform a few drops of blood into a red pigment that will probably be used to paint a tiny surface.

In a general way, whether they are addressed to painters, illuminators, dyers, or even doctors, apothecaries, cooks, or alchemists, all these recipe collections appear to be as much speculative texts as practical works. They share the same sentence structures and vocabulary, especially with regard to verbs: take, choose, gather, crush, grind, mill, boil, mix, stir, add, filter, steep. They all stress the importance of the slow work of time—wanting to speed up the process being neither effective nor honest—and the meticulous choice of containers: clay, iron, tin, opened or closed, wide or narrow, large or small, one particular shape or another, each designated by a specific word. What happened within those receptacles was on the order of metamorphosis, a mysterious and dangerous operation that required many precautions in the selection and use of the container. All the collections intended for painters pay attention to the issue of mixing and the use of different materials: mineral was not vegetable; vegetable was not animal. One could not do just anything with anything: vegetable was pure, animal was not; mineral was dead, vegetable and animal were living. For making a pigment, often the essence of the operation consisted in making a material considered to be alive act upon a material considered to be dead: fire on iron; madder or kermes on aluminum salts; vinegar or urine on copper.

Dyers at work. Bartholomaeus Anglicus and Jean Corbechon, Le Livres des Propriétés des Choses, manuscript copied and painted in Brussels, 1482.

Thanks to recipe collections in manuscript form, the first printed manuals, and analyses done in laboratories, we have good knowledge about the materials involved in the composition of pigments used by illuminators and painters in the late Middle Ages and the early modern period. For reds, the list is long but the materials hardly differ from those in use in ancient Rome: cinnabar (natural mercuric sulfide, rare and costly), realgar (natural arsenic sulfide, unstable and even more rare), minium (white lead artificially heated, very commonly used), and, especially for mural painting, clays rich in iron oxide, either naturally red (hematite) or heated to transform yellow ocher into red ocher. To this list of mineral pigments were added pigments of vegetable or animal origin: dyeing lacquers (madder, kermes, brazilwood) that painters liked because, like clays, they were very resistant to light; and sandarac, a reddish resin obtained from an Asian palm, the rotang. In the end, the Middle Ages added only a single red pigment to this list: vermilion, an artificial mercuric sulfide, obtained through the chemical synthesis of sulfur and mercury. Like natural cinnabar, this was a very toxic pigment, perfected in China, familiar to Arab alchemists, and arriving in the West between the eighth and eleventh centuries. It provided a beautiful orange-red, but had the disadvantage of darkening in the light of day.

The late Middle Ages and the modern period have left us works by great painters that are particularly remarkable for their range of reds. Let us mention Van Eyck, Uccello, Carpaccio, Raphael, and later, Rubens and Georges de La Tour. But all artists seemed to love this color and tried to draw various tonalities from it. Accordingly they chose their pigments, taking into account not only their physicochemical properties, their ability to cover or make opaque, their resistance to light, and how easily they could be worked or combined with other pigments but also their price, availability, and—what is most disconcerting to us—the name they went by. Indeed we can observe in the laboratory that in panel paintings from the late Middle Ages, symbolically “negative” reds—those coloring the fires of hell, the face of the Devil, the coat or feathers of infernal creatures, and all impure blood of one kind or another—were often painted with the same pigment: sandarac, a resin lacquer more commonly called “cinnabar of the Indies” or “dragon’s blood.” Various legends circulated in workshops regarding this pigment, a relatively expensive one because it had to be imported from far away. It was believed to come not from a plant resin but from the blood of a dragon, gored by its mortal enemy, the elephant. According to medieval bestiaries, which followed Pliny and the ancient authors here, the inside of the dragon’s body was filled with blood and fire; after a fierce struggle, when the elephant had punctured the dragon’s belly with its tusks, out flowed a thick, foul, red liquid, from which was made a pigment used to paint all the shades of red considered evil. Legend won out over knowledge in this case, and painters’ choices gave priority to the symbolism of the name over the chemical properties of the pigment.

Unlike the dyers, the painters of the modern period hardly profited at all from the discovery of the New World or the settling of Europeans in the Americas. No truly new colorants resulted from these events. But Mexican cochineal, transformed into lacquer, allowed them to perfect a subtle, delicate pigment in the range of reds, superior to earlier lacquers from brazilwood or kermes for fixing a glaze over vermilion. Beginning in the sixteenth century, vermilion experienced a steady rise in popularity and its production became something of an industry, first in Venice, the European capital of color, and then in the Netherlands and Germany. It was sold in apothecaries, hardware shops, and paint stores, and even though it was more expensive and less stable than minium, it eventually contributed to that pigment’s decline.

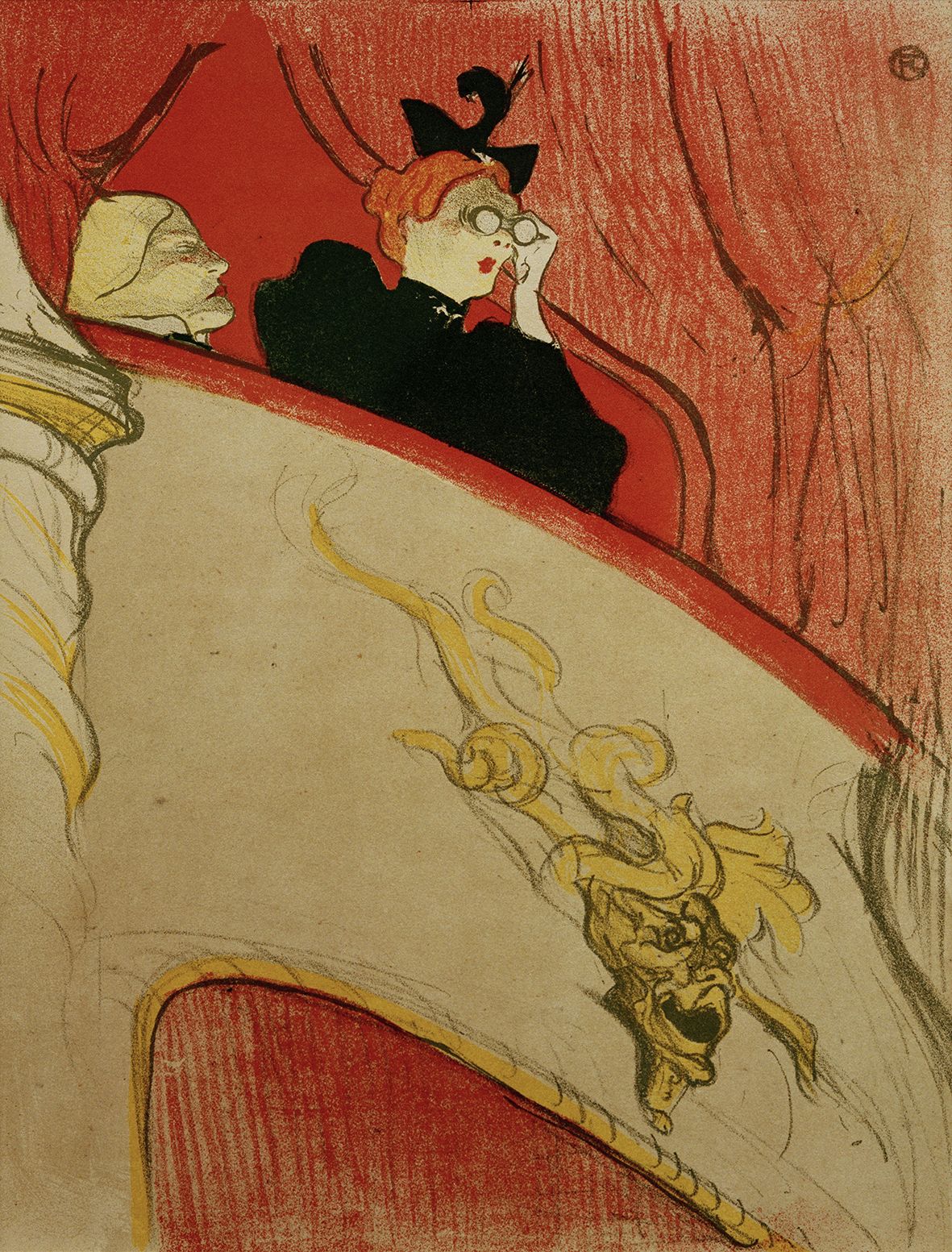

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, The Box with the Golden Mask, oil on paperboard, 1894. Vienna, Albertina. © AKG Images

Excerpted from Red: The History of a Color by Michel Pastoureau, available now from Princeton University Press.

Translated from the French by Jody Gladding.

Michel Pastoureau is a historian and director of studies at the École Pratique des Hautes Études de la Sorbonne in Paris. A specialist in the history of colors, symbols, and heraldry, he is the author of many books, including Green, Black, and Blue and The Devil’s Cloth: A History of Stripes. His books have been translated into more than thirty languages.