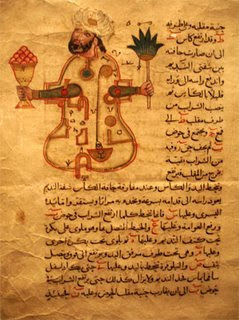

(Image of Hephaestus courtesy of Classics Unveiled)

and were like real young women, with sense and reason, voice also and strength, and all the learning of the immortals...

- The Illiad, Book 18

I just finished reading an article by Noel Sharkey in New Scientist (a British science magazine, totally worth the exhorbitant yearly subscription), which expanded on Mark Rosheim's wonderful and interesting book, Leonardo's Lost Robots.

Mr. Rosheim's research on Leonardo da Vinci's work suggests that da Vinci's lion automaton (see Wired article here) was powered by a clockwork cart, which was steered via a mechanism "controlled by arms attached to rotating gears." In Rosheim's opinion, it would have been possible to control the lion's movements by changing the position of the arms, which means the automaton was not only clockwork, but programmable. Which is a big deal.

Inspired by Rosheim's work, Mr. Sharkey, a professor of artificial intelligence and robotics at the University of Sheffield, decided to investigate some questions this raised: was da Vinci influenced by an earlier design? How far back in history can we trace programmable robots?

Mr. Sharkey is careful to point out that "programmable" means a machine capable of taking instructions. The instructions (the "program") can be written, or they can be hard-wired. The important thing is that the instructions should be able to be changed without taking the machine itself apart. So, for example, an old-fashioned metal-drum music box is reprogrammable because you can take the drum out and put a new one in.

This is what Sharkey says about his search:

"In search of answers I followed the technology back through medieval Europe to the Islamic world, where I have found evidence of an even earlier programmable automaton, made in Baghdad by the brilliant 13th-century engineer Ibn Ismail Ibn al-Razzaz Al-Jazari. He created a veritable boatload of programmable robot musicians effectively a floating jukebox designed to entertain nobles as they drank and lounged at royal pool parties.

"Picture of the internal structure of an automata for serving and arbitrating drinking sessions."

- Courtesy of JC Heuden at Virtual Worlds

Yet the trail doesn't stop there. It led me even further back past the automata of the Byzantine court and ancient Rome to ancient Alexandria. It was here that Hero, one of the greatest Greek engineers, constructed a programmable robot that pre-dates da Vinci's by 1500 years. Its control system turns out to be unique; more like knitting than a computer circuit. Nevertheless, there is clear evidence linking Hero's design to the programming languages used in, say, Honda's latest humanoid robot Asimo."

What Sharkey found was that Hero, who had designed everything from the aeolipile (the world's first steam-engine, see picture above) to "a vending machine that dispensed a shot of holy water in exchange for a coin," had designed a mobile theatre, complete with Dionysus and some female worshippers, all automata, which came in on a sort of self-propelled, self-guided cart. Sharkey saw the similarity to da Vinci's lion at once. But when he looked in Hero's Peri automatopoietikes ("On automata-making"), it became clear: this theatre was actually programmable -- using string for the programming language.

What Sharkey found was that Hero, who had designed everything from the aeolipile (the world's first steam-engine, see picture above) to "a vending machine that dispensed a shot of holy water in exchange for a coin," had designed a mobile theatre, complete with Dionysus and some female worshippers, all automata, which came in on a sort of self-propelled, self-guided cart. Sharkey saw the similarity to da Vinci's lion at once. But when he looked in Hero's Peri automatopoietikes ("On automata-making"), it became clear: this theatre was actually programmable -- using string for the programming language.

As Mr. Sharkey describes it, "Hero's idea was so elegant that even as I read it, the hairs on the back of my neck stood on end." Not only did Hero come up with a way of making a machine work in complex, programmable ways, he had essentially invented a programming language. And it's all with the kind of stuff you could put together in your basement. I found it all absolutely fascinating, but too long to recount, so you can read more in this reprint of the New Scientist article if you're interested. And here is a guy from New Scientist who decided to try it:

It's really interesting to me, finding that our mechanical-thinking personalities as humans go back so far. We tend to think of ourselves as the pinnacle of evolution, as if the ancient Greeks didn't have the brains to figure out simple mechanics. We look back and say, "My goodness, how on earth did they build those pyramids?" When in fact, the human brain hasn't changed in a really, really long time. It's only the available materials, the access to information, that have changed: the evolution of technological materials and our knowledge about what kinds of materials work, and the ability for information to move around in a sparsely-populated world full of war and danger - not the actual abilities of our minds. Think about it: Hero's book was probably read by, at best, a few hundred people over the course of several hundred years. Perhaps the reason we find it all so amazing is the way the ancients figured ways to be mechanical despite the lack of materials and access to information.

Take, for example, the article in the New Yorker recently (5/14/07) about the Antikythera mechanism (wiki), a fully-formed bronze clockwork mechanism from the first century BC:

"The device is remarkable for the level of miniaturization and complexity of its parts, which is comparable to that of 18th century clocks. It has over 30 gears, although some have suggested as many as 70 gears, with teeth formed through equilateral triangles. When past or future dates were entered via a crank (now lost), the mechanism calculated the position of the Sun, Moon or other astronomical information such as the location of other planets." - Wikipedia

When it was first opened in 1902, it was noticed that the Antikythera Mechanism had gears with precisely-cut teeth of different sizes, and looked like the mechanism of a clock, which was deemed impossible "because scientifically precise gearing wasn't believed to have been widely used until the fourteenth century - fourteen hundred years after the ship went down." No one wanted to believe it - and so the thing was put down as a sort of astrolabe - and left at that.

The interesting thing about this article, aside from the wonderful detective tale showing the slow unveiling of this device, is the unusual supposition that "early civilizations were much more technically adept than we imagine they were." In fact, let me quote a paragraph:

The interesting thing about this article, aside from the wonderful detective tale showing the slow unveiling of this device, is the unusual supposition that "early civilizations were much more technically adept than we imagine they were." In fact, let me quote a paragraph:

"Looking back over the first fifty years of research on the Mechanism, one is struck by the reluctance of modern investigators to credit the ancients with technological skill. The Greeks are thought to have possessed crude wooden gears, which were used to lift heavy building materials...but historians do not generally credit them with possessing...gears cut from metal and arranged into complex 'gear trains' capable of carrying motion from one driveshaft to another...It's almost as if we wished to reserve advanced technological accomplishment exclusively for ourselves."

The article goes on to describe how ancient inventors and their descriptions are the cause of much disbelief and furor among scholars, many of whom point to the lack of physical evidence. Hero's works are described by critics as "fantasy," for example. And yet, here is a perfectly fine specimen of ancient technology, sitting in a museum for a hundred years, gathering dust, while people argue about it in a desultory way (with a few, noticeably ignored, exceptions).

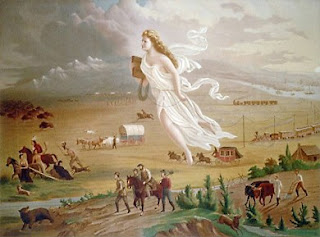

There is a quality to this kind of argument, among perfectly reasonable history- and science-types, which smacks to me of the Self-Justifying Three: Manifest Destiny, Social Darwinism, and Positivism. Manifest Destiny was a peculiarly American argument used in the 19th Century to excuse the displacement of indiginous peoples. It ran like this: the (white) American people are virtuous, and have a mission to spread this virtue, as manifestly destined by God (the destiny can be seen in how we are already spreading)...See the excellent, circular logic? Social Darwinism believes that extreme inequalities in wealth are due to the fact that anyone who's got the right stuff will become rich, therefore the poor must be inherently lazy and stupid, and that's why they're poor. Positivism is still alive and well today, and it says that everything is improving through science, i.e. continually getting more rational (read: better - remember "Better living through chemistry?") Apply all this to the ancients, and we have exactly the kind of assumed superiority that gets us nowhere.

"This painting (circa 1872) by John Gast called American Progress is an allegorical representation of Manifest Destiny. Here Columbia, a personification of the United States, leads civilization westward with American settlers, stringing telegraph wire as she travels; she holds a schoolbook. The different economic activities of the pioneers are highlighted and, especially, the changing forms of transportation. The Indians and wild animals flee." [wiki]

Think about it: why do people always say that Leonardo da Vinci was "ahead of his time?" It's true that he was brilliant, but doesn't that statement imply a certain belief that those people back then were incapable of creation to the degree he worked, that they were not only ignorant but, somehow, less than modern people?

The problem is confusing intelligence with knowledge, and knowledge with information. How many of us remember the "smart" kid in school, the one who knew everything? In reality this kid wasn't much smarter than other people, it was simply that he or she kept all the facts at his or her fingertips. On the other hand that other kid, the quiet one in the corner who never said anything? That kid was actually mechanically brilliant, but no one noticed it because it expressed itself as spending all her time "playing with" her Erector Set (aka Meccano). We have all done it, thinking that knowledge is the product of intelligence - and also that information is knowledge.

The truth is that knowledge is the assembly of information, and it is only through intelligence that we are able to convert knowledge into a coherent world view. If we saw it in terms of Lego (since I'm on a toy theme here), information would be the individual lego blocks - useless on their own. Knowledge would be lego blocks assembled into discrete chunks, which allows the legos to be carried around and exchanged - but they still don't mean much, other than the cachet of personal wealth, until you add in that secret ingredient: intelligence. Then, all of a sudden, you can make all sorts of things happen that have never been done with legos before.

In the world of education, it is becoming more and more commonly believed that intelligence comes in many different flavors, and that, contrary to IQ tests and other ways of quantifying smarts, intelligence has to do with ways of perceiving, ways of processing knowledge. If you look at the fact that there are more than ten times the number of people alive today than in da Vinci's time (and less before that), it is no wonder that this innate intelligence did not catch fire, and Hero's steam-powered aeolipile (for example) remained a curiosity.

After all, he was unable to broadcast what he did except in the most limited way, lacking a printing press or a postal system.

After all, he was unable to broadcast what he did except in the most limited way, lacking a printing press or a postal system.

Giambattista Vico (1668-1744), who rebutted the presiding Cartesian view that all things must be verified through observation by observing that "the realms of verifiable truth and human concern share only a slight overlap, yet reasoning is required in equal measure in both spheres" [wiki], said that history is cyclical. His analysis was that civilization repeats the same cycle every time: a "divine" age, where culture relied on metaphor to understand the world; a "heroic" age, feudal and monarchic and dependent on idealized figures, and the final age, which is characterized by democracy and reflection on the world via irony (which era do you suppose we are in?). "...in this [final] epoch, the rise of rationality leads to barbarie della reflessione or barbarism of reflection, and civilization descends once more into the poetic era" [wiki]. Needless to say, he got a poor reception for his ideas, because no one wanted to believe that civilizations always rise and fall again. Everyone wants to believe that they are the pinnacle of history, and that it will carry on this way forever.

The truth is, even when people came up with great ideas, they might not have had the means to disseminate information. And even if they did, the ideas had difficulty going far. And even then, you were always in danger of running into a dark age, when all your ideas were burned or lost or, well, suppressed.

So here we are, with our internet and our intense crowding, where ideas fly around like bees. When someone invents something it is disseminated within minutes. Can you see the advantages we have over the ancients? We must be careful we do not assume an evolutionary advantage over those who have gone before - that we, with all our gear, are actually more intelligent than our ancient forebears, who when you think of it, did the most amazing things with the materials at hand. Perhaps the sign of a truly advancing culture is one who can overcome the urge to diminish those who have come before. Perhaps, when articles like this come out in the New Yorker and other popular broadcasting mechanisms, we have some hope; a Rennaissance of sorts.

Or perhaps we should be on the lookout for that coming Dark Age.

Links:

July 31st the History Channel is running a show on Ancient Robots, in which they have interviewed Mr. Sharkey. The dates for this in the UK start, I think, on the 24th - look it up depending on your area. I have no idea about the rest of the English-speaking world, sorry...

Thanks to the Automata/Automaton blog for the unexpected link to YouTube!