Tiny pieces of plastic are making their way into fish and shellfish found at the supermarket, a new study has shown.

The findings are part of a report prepared for the International Maritime Organization, the UN agency responsible for preventing marine pollution.

It's not yet been established what effect these tiny particles of plastic will have on the humans who consume them, the report says.

Researchers do know, however, that microplastics get into aquatic habitats from many different sources, says Chelsea Rochman, an assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Toronto and co-editor of the report.

'It has infiltrated every level of the food chain in marine environments … and so now we're seeing it come back to us on our dinner plates.'- Chelsea Rochman, University of Toronto ecologist

These range from tiny fibres that come off the synthetic fabrics of our clothing, to bits of car tire that wear off on roads and make their way through storm drains into waterways, she says.

They also vary in size such that they can be consumed by marine animals both big and microscopic.

"It has infiltrated every level of the food chain in marine environments and likely fresh water, and so now we're seeing it come back to us on our dinner plates," says Rochman.

Gutting fish won't rid them of the bits of plastic they consume.

"These materials enter marine organisms, not just their guts but also their tissues," says Peter Wells, a senior research fellow with the International Ocean Institute at Dalhousie University.

A net designed to gather samples of microplastic particles is dragged through Lake Ontario on July 15, 2015. (Micki Cowan/CBC)

And it's not just the plastic itself, but the stuff that comes along with it, that's a concern, says Wells.

Microplastics absorb or carry organic contaminants, such as PCBs, pesticides, flame retardants and hormone-disrupting compounds of many kinds, he says.

Wells says that until recently, the world's attention was on larger pieces of plastic in the ocean — the kind of garbage obviously visible to the naked eye.

Pictures of seabirds with plastic rings from six-packs of beer around their necks were shared with alarm, for example.

"Only when scientists started looking at plankton and water samples more carefully did they realize that a lot of the plastic was being broken down, not seen except under a microscope," says Wells.

Not just microbeads

Among all the microplastics in our lakes and oceans, microbeads — those little exfoliants from facial scrubs and hand soaps — are the best known by the public.

"Microbeads are really what brought microplastics to the table in Canada as something that we would regulate and monitor," says Rochman. A federal government ban on toiletries containing microbeads will come into effect in 2018.

However, these are not the main source of microplastics, she says.

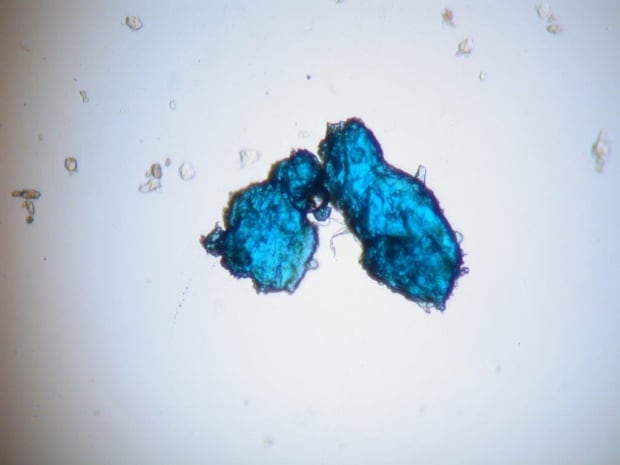

Microbeads, like these from a sample of toothpaste seen under a microscope, are the best known among microplastics but not the most common source, says Chelsea Rochman, co-editor of the report. (Dr. Harold Weger)

"The biggest source is likely larger plastic items that we can see during beach cleanups that enter the water and over time break down with the sunlight into smaller and smaller pieces of microplastic."

Think plastic bags, styrofoam takeout containers and plastic cutlery, says Rochman.

What does this mean for fish as food?

Kate Comeau, a registered dietitian and the spokeswoman for Dietitians of Canada, cautions consumers not to come to conclusions too quickly as a result of these findings.

"It's an important conversation," says Comeau, "but we don't want people running away from eating healthy sources of food."

Fish is an excellent source of protein, she says. "The fatty fish are also a great source of vitamin D, which we don't have a lot of food sources of in our Canadian diet. Fish is also a great source of iron, and those omega-3 fats are really important in terms of our heart health."

Rochman stresses that more research is required before anyone lets microplastics determine what's for dinner.

"What we really need to do is a risk assessment … nobody has done that for microplastics."

Researchers have found microplastics in molluscs like oysters both in field research and in retail outlets, says Rochman. (Cameron Spencer/Getty Images)