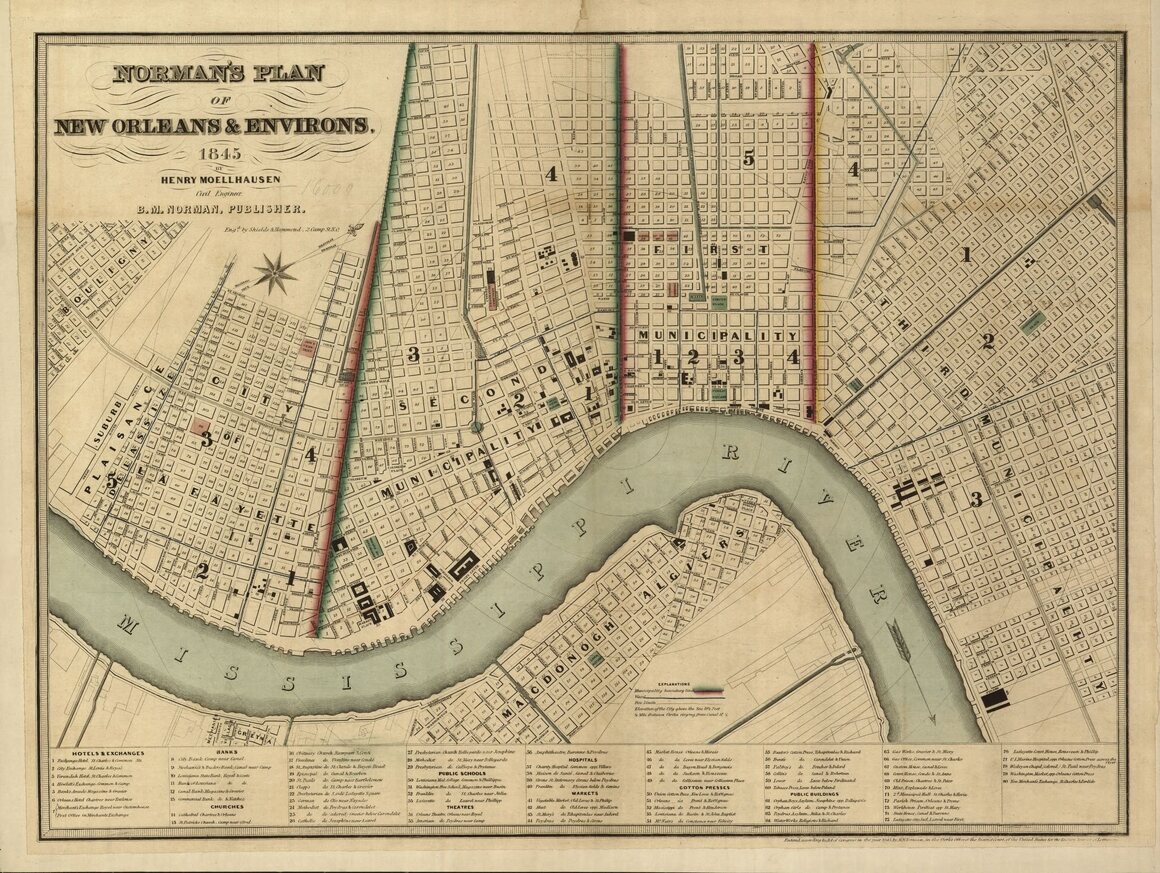

In 1803, when the United States bought New Orleans, along with the rest of the land in the Louisiana Purchase, the city had only about 8,000 people living in it. Planned on a tight grid, the city stretched just eleven blocks along a curve of the Mississippi River and six blocks back from the levee, to Rampart Street.

A little more than three decades later, New Orleans had become a world port, and in 1836 edged out New York City as the busiest export center in the United States. The population had grown to more than 60,000 people—many of them Anglo-Americans who, to the alarm of the city’s Francophone natives, had flocked to the port to make their fortunes.

Today, New Orleans trades on the languid charm of its French and Spanish past to lure visitors to its historic center, but in the early 19th century, American newcomers to the city had no patience for Louisiana’s old guard, known as creoles, whom they saw as Catholic, corrupt, and overly permissive to the city’s large population of slaves and free people of color.

But in New Orleans, the American upstarts lacked the political power to change the city’s ways as fast as they would like. Instead, in 1836, the city’s Anglo-Americans convinced the state legislature to split New Orleans into pieces—three semi-autonomous municipalities divided along ethnic lines. For more than 15 years, the city was divided, while the Americans consolidated their power and re-shaped the city to their own ends.

The idea of dividing New Orleans between the Francophone old guard and the Anglophone newcomers first came up in the 1820s, when rival military factions would challenge each other’s authority, edging towards but never quite exploding into violent conflict. In his book Louisiana in the Age of Jackson, Joseph G. Tregle, Jr., the Louisiana historian who has studied this period most closely, tells how American-led sections of the militia would refuse to follow orders from foreign French officers who still held military positions. When Americans held command, the French would reciprocate.

At times, different factions of the militia would march through the streets, showing off their defiance and power, and it was during one such conflict that a local American editor, R.D. Richardson, started calling for the city to be split along ethnic lines. A rival French editor, who had fought for Napoleon, responded by offering five dollars to anyone who’d give Richardson a good whap over the head.

There were two main areas in which the entrenched French creoles made the incoming Americans crazy. The first was infrastructure: when the U.S. bought the Louisiana territory, New Orleans had no paved roads, no street signs, and no colleges. Much of the population was illiterate, and justice was dispensed according to the French legal code: Tregle calls the place “a colonial backwash of French and Spanish imperialism.”

The second was the permissive culture: Sunday in New Orleans means sitting at a café and going out dancing or perhaps to a horse race. In this city, black and white people mingled more freely than elsewhere in America, and even slaves had more leeway to move freely than in other cities.

All this shocked the Protestant, Puritan-minded American settlers, many of whom came from places in the South where the movement of black people was highly restricted and regulated. (Meanwhile, the native creole population was appalled by the crude Americans, who they called Kaintucks and vulgar Yankees.) The Anglo-American settlers tried to change everything from the city’s laws to the looser culture, but even as they gained power of New Orleans’ commercial life, they did not have enough political power to mold the city as they would have liked.

After the conflicts of the 1820s, the newcomers kept trying to split the city—if they couldn’t fix the whole place, at least they could control part of it. About a decade later, in 1836, Anglo-Americans finally got their way. New Orleans was divided into three municipalities, one Anglophone and two Francophone.

The three sections of split New Orleans roughly correspond to the today’s Central Business District, French Quarter, and Marigny neighborhood. The Second Municipality, which the Americans controlled, began at Canal Street and went upriver, past the place where the Pontchartrain Expressway cuts through the city today. The First Municipality included all of the French Quarter, from Canal to Esplanade Avenue, and the Third Municipality stretched downriver from there, through the Marigny towards today’s Bywater neighborhood. Each municipality had its own police force, its own schools, its own infrastructure, and services. In the First Municipality, English was the language of commerce and government; in the other two, French dominated.

When this story is told quickly, it’s usually said that New Orleans was a place neatly divided between old and new, French and English, a more multiracial society and a white one, with Canal Street as the clear border. But according to the work of Tregle and later historians, the divide was not initially so stark as legend might have it.

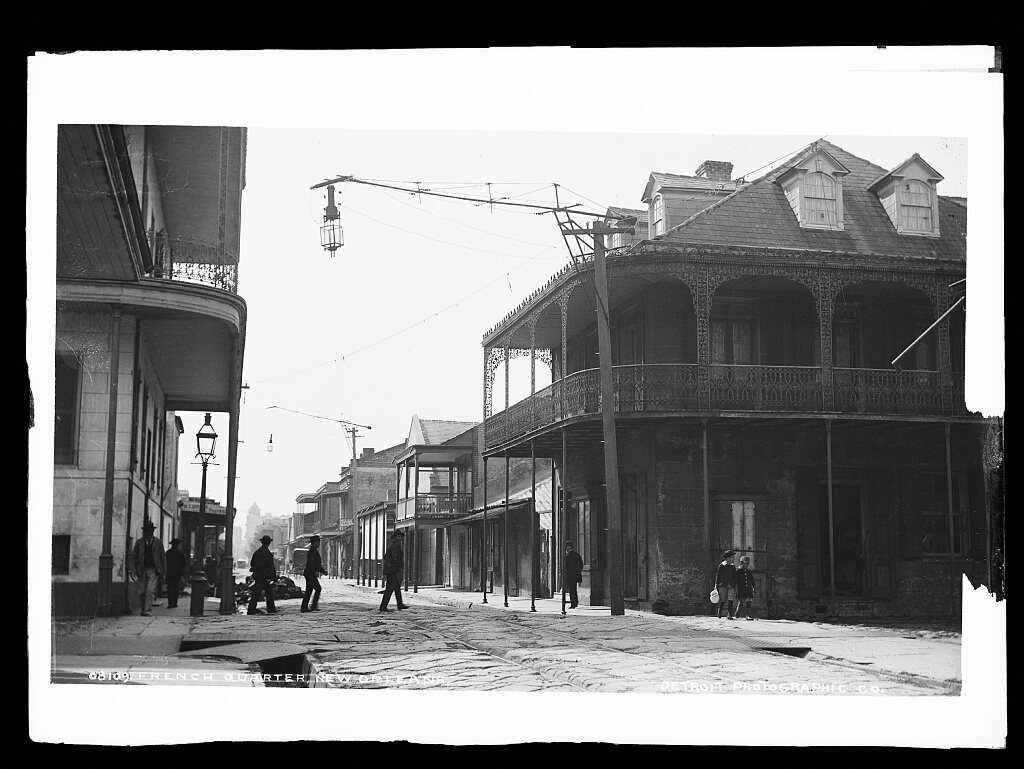

When Americans started moving to New Orleans, they moved first to the French Quarter, on the upriver side, closer to Canal Street. Only once that section of town filled up did they continue building into Faubourg Ste. Marie, the newer suburb on the far side of Canal. It was always desirable to live in the French Quarter, where by the 1830s Chartres Street had become a major commercial thoroughfare, dotted with American shops selling books, jewelry, and other goods. On the other side of Canal Street, it was common for prominent Francophone creoles to make their home in Ste. Marie, too. To the extent that there was a clear dividing line between the old and new populations, it was at St. Louis Street, close to the center of the city.

But once the city was divided in three political entities, the distinctions between the Second Municipality and the other two started to grow. Trade in the Second Municipality thrived, and bustling warehouses and insurance companies started going up on Camp and Magazine streets.

The growing economy led to a housing boom, where Greek revival architecture mixed with the brick-faced warehouses of a northeastern port city; one traveler noted that the American part of the city “lacked that mellowness of age and charm of the bizarre which set old New Orleans apart.” Whatever it lacked in beauty, though, it made up for in wealth and city services: the Second Municipality soon had a modern school system, as well as new wharves, gas lights, and paved streets.

On the other side of town, the area below Jackson Square was suffering, as poverty increased and the old French houses aged. The Third Municipality, sometimes called the “The Dirty Third,” was in particularly bad shape, since the waste of the rest of the city floated downriver to pollute its shores, air, and water. By the time the city was reunited, in 1852, its wealth had concentrated upriver: Tregle found that by 1860 the area upriver of St. Louis Street had 76 percent of the city’s taxable property.

More than any other American city at the time, New Orleans could claim to be a diverse place where people of color had more freedom than elsewhere in the South. But during the period where white newcomers divided New Orleans, the American values and laws that were shaping both the city and the new state of Louisiana were reducing those freedoms quickly. The American values imported to New Orleans included not just an emphasis on better infrastructure and education, but on more legally encoded racism, that was strictly enforced.

“On the upper side of town…white inhabitants were often times more hostile to the very notion of free people of color,” writes Richard Campanella, a contemporary historian who studies New Orleans geography. The white Americans who were gaining power were uncomfortable with the rights that slaves and free people of color had in the city and sought to restrict their movements and freedoms. There was also a second major wave of white people coming to the city, who saw themselves as being in conflict with the black population. During the 1830s, immigrants from Ireland and Germany flocked to New Orleans and made it a majority white city for the first time: in 1835, white workers protested black employment in certain desirable jobs.

As much as the division allowed trade to thrive and infrastructure to improve in parts of New Orleans, it was mostly to the benefit of white, American-born people. When the city did merge back into one city, it was only because the Anglo-Americans had enough power to control not just commerce but city politics, too. With the influx of immigrants, they outnumbered the Francophone old guard. The immigrant-heavy suburb of Lafayette was incorporated into the city, becoming today’s Garden District. Only once the Anglo-Americans could shift the whole city to their own ways did they let it become whole again.