The "tough on crime" prosecutor's days may be numbered.

Over the past few days, news has trickled out that liberal billionaire George Soros has poured millions of dollars into local election campaigns against "tough on crime" prosecutors, helping defeat one such prosecutor in Illinois earlier this year and dropping money into races ranging from Mississippi to New Mexico. And Angela Corey, the "tough" state's attorney for the Fourth Judicial Circuit in Florida, handily lost her reelection bid 64-26 to fellow Republican Melissa Nelson.

At first glance, the decision to spend so much money and attention on these local elections may seem odd. These aren't the elections that typically draw a lot of mainstream media or public attention.

But the effort is the result of a steady build-up of attention toward prosecutors over the past few years, as progressive reformers like Soros — who wants to end mass incarceration— have realized just how much of a role these prosecutors play in the justice system while receiving almost no accountability from voters.

Until now, the political system and voters haven't really held prosecutors accountable. About 95 percent of incumbent prosecutors won reelection, and 85 percent ran unopposed in general elections, according to data from nearly 1,000 elections between 1996 and 2006 analyzed by Ronald Wright of Wake Forest University School of Law.

But prosecutors are enormously powerful in the criminal justice system. They decide which laws will actually be enforced, with almost no checks on that power outside of elections. For instance, in 2014 Brooklyn District Attorney Kenneth Thompson announced that he will no longer enforce low-level marijuana arrests. Think about how this works: Pot is still very much illegal in New York, but the district attorney flat-out said that he will ignore an aspect of the law — and it's completely within his discretion to do so.

A prosecutor is also often the only public official standing between a defendant and prison time. More than 90 percent of criminal convictions are resolved through a plea agreement, so by and large prosecutors and defendants — not judges and juries — have almost all the say in a great majority of cases that result in incarceration or some other punishment.

Prosecutors have also been at the center of police killing investigations over the past year following the deaths of Freddie Gray in Baltimore, Eric Garner in New York City, and Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, among others. It was a prosecutor — Baltimore City State's Attorney Marilyn Mosby— who decided to file (unsuccessful) charges against the six officers involved in Gray's death. It was two prosecutors who guided the grand juries that decided not to file charges against the officers involved in Brown and Garner's deaths, with no one else able to dictate how prosecutors should run the hearings.

Despite all of these powers, voters and lawmakers very rarely force prosecutors to answer for their records — even as they play a key role in perpetuating the kind of mass incarceration that criminal justice reformers now want to end.

Prosecutors helped perpetuate mass incarceration

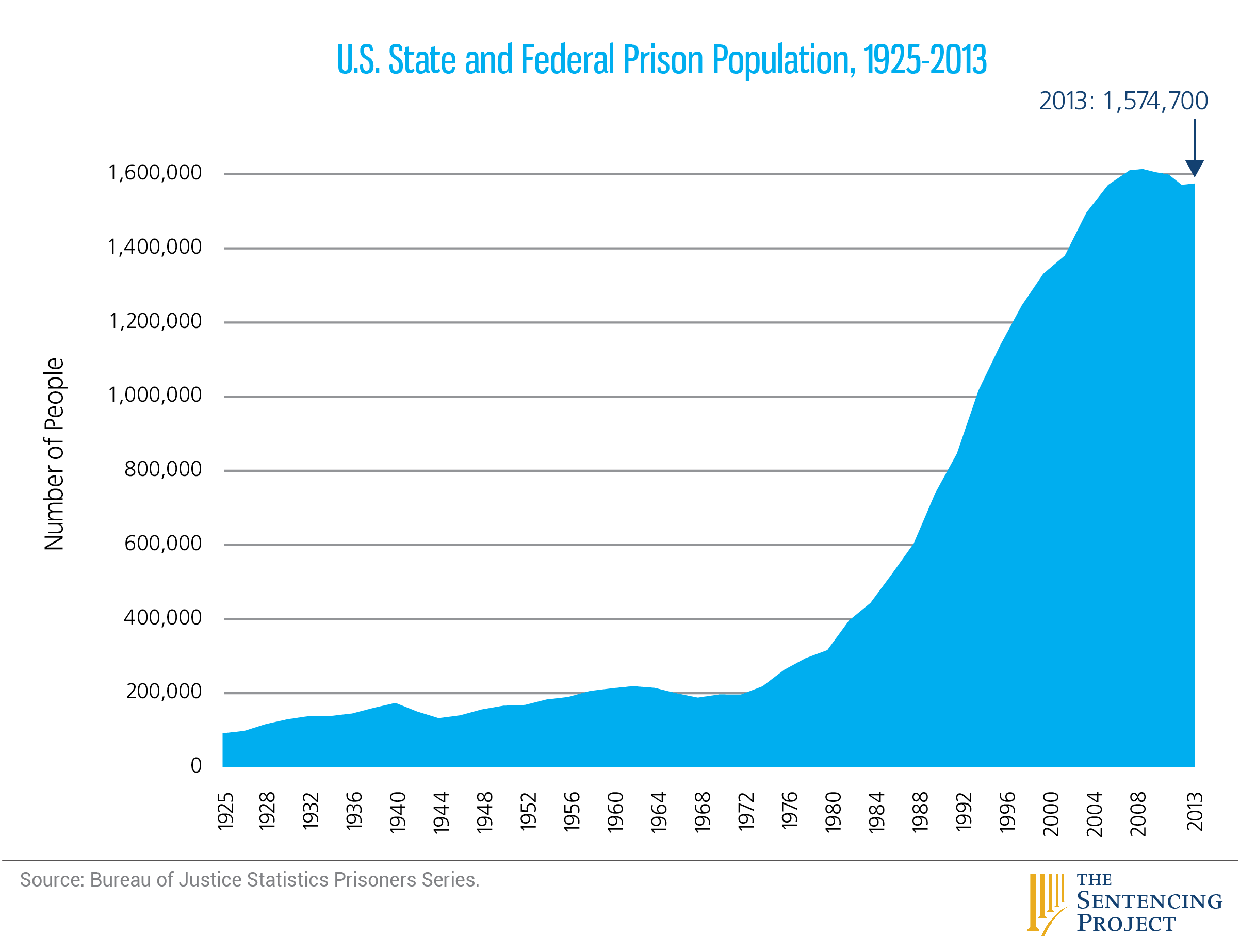

One of the most baffling aspects of the US criminal justice system is that incarceration rates continued to rise even after crime began dropping in the 1990s. If crime was dropping, it stands to reason that there should have been fewer criminals to lock up. But that's not what happened — and America continues to lead the world in incarceration, with more than four times the incarceration rate of countries like the United Kingdom, Canada, France, and Germany, and a higher rate than authoritarian countries like China and Russia.

When John Pfaff, a professor at the Fordham University School of Law, looked into this, he found something a bit surprising: His study concluded that prosecutors filed more charges in the 1990s and 2000s even as arrests dropped. So when someone was arrested by police, the prosecutor was generally more likely to file charges against that person in the 2000s than she was in the 1980s. And that led to more people in prison.

What explains prosecutors' actions? Pfaff uncovered data that showed prosecutors were more likely to go after people with longer criminal records, who now existed in greater numbers because of the war on drugs and other "tough on crime" policies enacted in the 1980s and '90s that pushed more people into the corrections system.

It's also possible that "tough on crime" laws have given prosecutors the ability to more confidently file charges. Prosecutors very often get plea deals by pointing to the possibility of much longer sentences — such as mandatory minimum sentences that can add up to decades in prison— to convince a defendant that it would be much safer to take the guarantee of a shorter prison sentence as long as they plead guilty. But prosecutors only have this ability now because of "tough on crime" laws passed in the 1980s and '90s extended prison sentences for all sorts of previously less punished and minor offenses.

"Prosecutors have always had the discretion of who to charge with a crime and the charges to file," Brian Elderbroom, a researcher at the Alliance for Safety and Justice, said. "The difference now is they have this tremendous leverage through longer sentences."

Politics may play a role, as well. Although prosecutors are rarely threatened in their own reelections, they may feel compelled to look tough on crime in case they run for other offices. It's not unheard of, after all, for a district attorney to climb from that position to representative, senator, mayor, attorney general, or even governor.

"They're political actors in that they're not just concerned about remaining [district attorney]. They might want that next job," Pfaff said. "So perhaps they remain tough on crime not because they need to remain tough on crime to win the [district attorney] election, but they need to remain tough on crime to have a shot at attorney general, governor, or congressman."

There's little data on what prosecutors actually do

Ramin Talaie/Getty Images

Should the Department of Justice, which Attorney General Loretta Lynch heads, collect data on what prosecutors do?

One reason it might be difficult for the public or lawmakers to hold prosecutors accountable is because there's simply no good data on what they're doing.

"We have no data, nationally, on the number of people that prosecutors are putting in prison versus the number that they're keeping in the community by either placing them on probation or some other alternative to incarceration," Elderbroom said. "So it'd be really helpful if we had some sort of national prosecutors reporting program the way we do around corrections."

This applies at the state level, too, Pfaff explained. Some jurisdictions — like New York City — may have good data on what prosecutors are doing. But that's not the case in much of the country, where prosecutors don't file records that would explain why, for example, they pursued prison time instead of probation for a defendant. "We don't really know why prosecutors do what they do," Pfaff said.

Part of the reason for that may be costs. Good data collection takes time and money. New York City's district attorneys may already have the staff and resources to do it, but other prosecutors, particularly in rural areas, are going to require more funding — perhaps support from the state — to do it. "They don't all have large staffs," Pfaff said. "It would be a huge investment on the part of the state to figure out how to fund that."

This is in many ways symptomatic of the criminal justice system. We still don't have, for example, good data on police shootings or how many police are killed on the job. And criminologists widely acknowledge that the federal government's crime statistics likely underreport crime. But while those gaps in data have gotten attention from mainstream media outlets and former Attorney General Eric Holder, there's little movement on improving data collection from prosecutors' offices.

States could limit prosecutors' powers

Charles Norfleet/Getty Images

Brooklyn District Attorney Kenneth Thompson wants to focus less on low-level marijuana charges. But New York could make all district attorneys focus less on marijuana by legalizing the drug.

If states don't want prosecutors to continue filing charges for certain crimes, one thing they could do is simply decriminalize or remove felony penalties from those offenses — therefore eliminating prosecutors' ability to file charges at all.

This is partly what California did in 2014 through Proposition 47, which changed a host of minor drug and property crimes into non-felonies. That means, for example, that prosecutors can no longer file a felony charge just because someone possesses cocaine. But it also means prosecutors can no longer threaten people with a big felony charge for cocaine possession to scare them into settling for a plea deal with less prison time or probation.

Pfaff explained this is why it's important for legislators to expand criminal justice reform so it doesn't just let prisoners get out of prison early, but actually changes what's a criminal charge and the sentence for those crimes — both to reduce prosecutors' ability to charge people and the leverage they have during negotiations for plea deals.

"Tough on crime" advocates argue that prosecutors need the long sentences to secure settlements from dangerous criminals and to avoid the costs and uncertainties that could come from a long trial and appeals process.

But as public officials — even the conservative governor of Georgia— look to reduce the US prison population to save money and move away from a justice system that many view as draconian, the data uncovered by Pfaff suggests that limiting prosecutors' powers will need to be a part of the solution.

"Absent those kinds of changes," Pfaff said, "there's very little we can do to keep a [prosecutor] from sending people to prison."