On December 29th, 2016 the White House released a statement from the President of the United States (POTUS) that formally accused Russia of interfering with the US elections, amongst other activities. This statement laid out the beginning of the US’ response including sanctions against Russian military and intelligence community members. The purpose of this blog post is to specifically look at the DHS and FBI’s Joint Analysis Report (JAR) on Russian civilian and military Intelligence Services (RIS) titled “GRIZZLY STEPPE – Russian Malicious Cyber Activity”. For those interested in a discussion on the larger purpose of the POTUS statement and surrounding activity take a look at Thomas Rid’s and Matt Tait’s Twitter feeds for good commentary on the subject.

Background to the Report

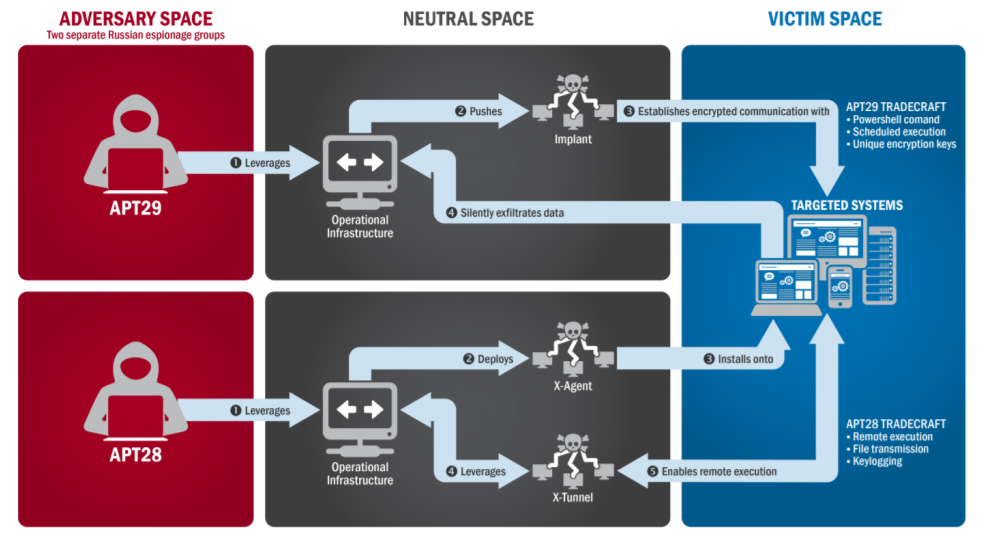

For years there has been solid public evidence by private sector intelligence companies such as CrowdStrike, FireEye, and Kaspersky that has called attention to Russian-based cyber activity. These groups have been tracked for a considerable amount of time (years) across multiple victim organizations. The latest high profile case relevant to the White House’s statement was CrowdStrike’s analysis of COZYBEAR and FANCYBEAR breaking into the DNC and leaking emails and information. These groups are also known by FireEye as the APT28 and APT29 campaign groups.

The White House’s response is ultimately a strong and accurate statement. The attribution towards the Russian government was confirmed by the US government using their sources and methods on top of good private sector analysis. I am going to critique aspects of the DHS/FBI report below but I want to make a very clear statement: POTUS’ statement, the multiple government agency response, and the validation of private sector intelligence by the government is wholly a great response. This helps establish a clear norm in the international community although that topic is best reserved for a future discussion.

Expectations of the Report

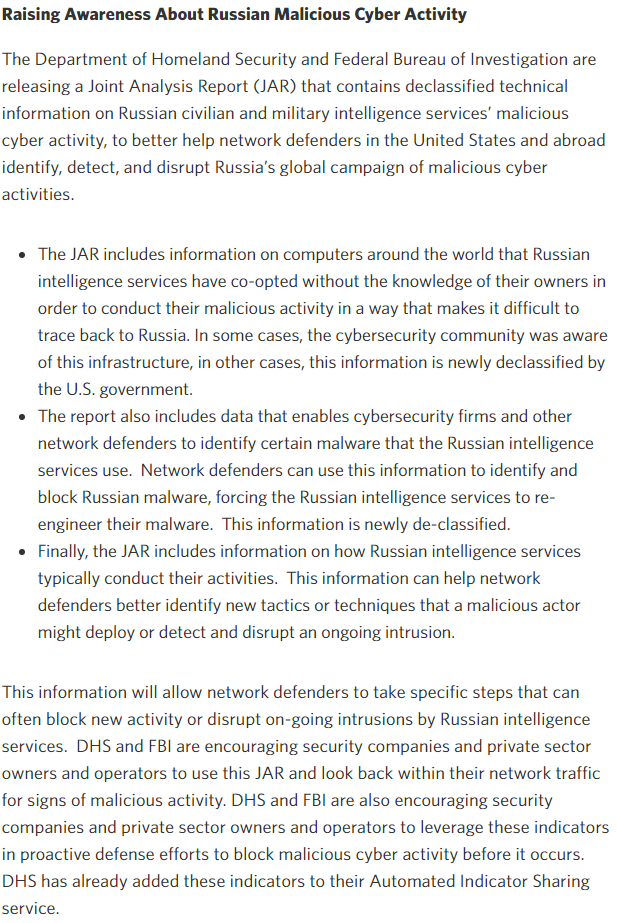

Most relevant to this blog, the lead in to the DHS/FBI report was given by the White House in their fact sheet on the Russian cyber activity (Figure 1).

Figure 1: White House Fact Sheet in Response to Russian Cyber Activity

The fact sheet lays out very clearly the purpose of the DHS/FBI report. It notes a few key points:

- The report is intended to help network defenders; it is not the technical evidence of attribution

- The report contains a combination of private sector data and declassified government data

- The report will help defenders identify and block Russian malware – this is specifically declassified government data not private sector data

- The report goes beyond indicators to include new tradecraft and techniques used by the Russian intelligence services

If anyone is like me, when I read the above I became very excited. This was a clear statement from the White House that they were going to help network defenders, give out a combination of previously classified data as well as validate private sector data, release information about Russian malware that was previously classified, and detail new tactics and techniques used by Russia. Unfortunately, while the intent was laid out clearly by the White House that intent was not captured in the DHS/FBI report.

Because what I’m going to write below is blunt feedback I want to note ahead of time, I’m doing this for the purpose of the community as well as government operators/report writers who read to learn and become better. I understand that it is always hard to publish things from the government. In my time working in the U.S. Intelligence Community on such cases it was extremely rare that anything was released publicly and when it was it was almost always disappointing as the best material and information had been stripped out. For that reason, I want to especially note, and say thank you, to the government operators who did fantastic work and tried their best to push out the best information. For those involved in the sanitation of that information and the report writing – well, read below.

DHS/FBI’s GRIZZLY STEPPE Report – Opportunities for Improvement

Let’s explore each main point that I created from the White House fact sheet to critique the DHS/FBI report and show opportunities for improvement in the future.

The report is intended to help network defenders; it is not the technical evidence of attribution

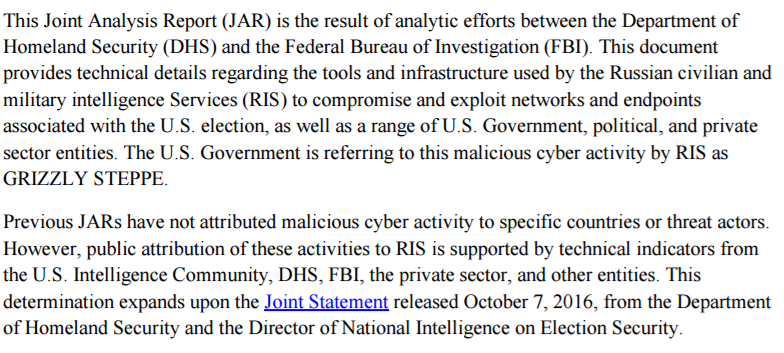

There is no mention of the focus of attribution in any of the White House’s statements. Across multiple statements from government officials and agencies it is clear that the technical data and attribution will be a report prepared for Congress and later declassified (likely prepared by the NSA). Yet, the GRIZZLY STEPPE report reads like a poorly done vendor intelligence report stringing together various aspects of attribution without evidence. The beginning of the report (Figure 2) specifically notes that the DHS/FBI has avoided attribution before in their JARs but that based off of their technical indicators they can confirm the private sector attribution to RIS.

Figure 2: Beginning of DHS/FBI GRIZZLY STEPPE JAR

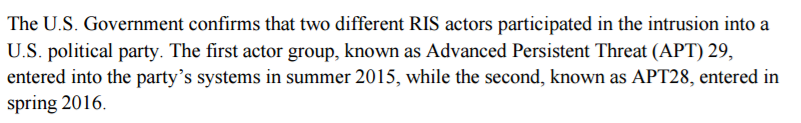

The next section is the DHS/FBI description which is entirely focused on APT28 and APT29’s compromise of “a political party” (the DNC). Here again they confirm attribution (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Description Section of DHS/FBI GRIZZLY STEPPE JAR

But why is this so bad? Because it does not follow the intent laid out by the White House and confuses readers to think that this report is about attribution and not the intended purpose of helping network defenders. The public is looking for evidence of the attribution, the White House and the DHS/FBI clearly laid out that this report is meant for network defense, and then the entire discussion in the document is on how the DHS/FBI confirms that APT28 and APT29 are RIS groups that compromised a political party. The technical indicators they released later in the report (which we will discuss more below) are in no way related to that attribution though.

Or said more simply: the written portion of the report has little to nothing to do with the intended purpose or the technical data released.

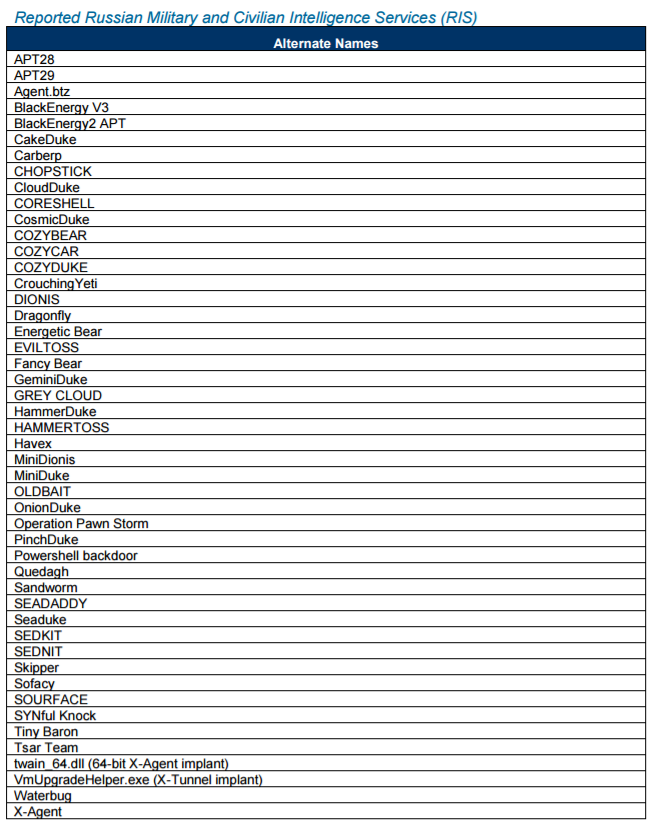

Even worse, page 4 of the document notes other groups identified as RIS (Figure 4). This would be exciting normally. Government validation of private sector intelligence helps raise the confidence level of the public information. Unfortunately, the list in the report detracts from the confidence because of the interweaving of unrelated data.

Figure 4: Reported RIS Names from DHS/FBI GRIZZLY STEPPE Report

As an example, the list contains campaign/group names such as APT28, APT29, COZYBEAR, Sandworm, Sofacy, and others. This is exactly what you’d want to see although the government’s justification for this assessment is completely lacking (for a better exploration on the topic of naming see Sergio Caltagirone’s blog post here). But as the list progresses it becomes worrisome as the list also contains malware names (HAVEX and BlackEnergy v3 as examples) which are different than campaign names. Campaign names describe a collection of intrusions into one or more victims by the same adversary. Those campaigns can utilize various pieces of malware and sometimes malware is consistent across unrelated campaigns and unrelated actors. It gets worse though when the list includes things such as “Powershell Backdoor”. This is not even a malware family at this point but instead a classification of a capability that can be found in various malware families.

Or said more simply: the list of reported RIS names includes relevant and specific names such as campaign names, more general and often unrelated malware family names, and extremely broad and non-descriptive classification of capabilities. It was a mixing of data types that didn’t meet any objective in the report and only added confusion as to whether the DHS/FBI knows what they are doing or if they are instead just telling teams in the government “contribute anything you have that has been affiliated with Russian activity.”

The report contains a combination of private sector data and declassified government data

This is a much shorter critique but still an important one: there is no way to tell what data was private sector data and what was declassified government data. Different data types have different confidence levels. If you observe a piece of malware on your network communicating to adversary command and control (C2) servers you would feel confident using that information to find other infections in your network. If someone randomly passed you an IP address without context you might not be sure how best to leverage it or just generally cautious to do so as it might generate alerts of non-malicious nature and waste your time investigating it. In the same way, it is useful to know what is government data from previously classified sources and what is data from the private sector and more importantly who in the private sector. Organizations will have different trust or confidence levels of the different types of data and where it came from. Unfortunately, this is entirely missing. The report does not source its data at all. It’s a random collection of information and in that way, is mostly useless.

Or said more simply: always tell people where you got your data, separate it from your own data which you have a higher confidence level in having observed first hand, and if you are using other people’s campaign names, data, analysis, etc. explain why so that analysts can do something with it instead of treating it as random situational awareness.

The report will help defenders identify and block Russian malware – this is specifically declassified government data not private sector data

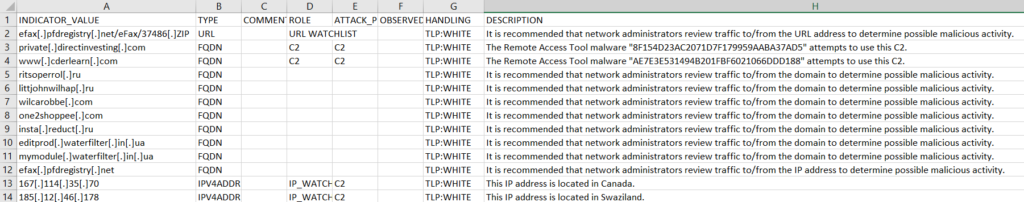

The lead in to the report specifically noted that information about the Russian malware was newly declassified and would be given out; this is in contrary to other statements that the information was part private sector and part government data. When looking through the technical indicators though there is little context to the information released.

In some locations in the CSV the indicators are IP addresses with a request to network administrators to look for it and in other locations there are IP addresses with just what country it was located in. This information is nearly useless for a few reasons. First, we do not know what data set these indicators belong to (see my previous point, are these IPs for “Sandworm”, “APT28” “Powershell” or what?). Second, many (30%+) of these IP addresses are mostly useless as they are VPS, TOR exit nodes, proxies, and other non-descriptive internet traffic sites (you can use this type of information but not in the way being positioned in the report and not well without additional information such as timestamps). Third, IP addresses as indicators especially when associated with malware or adversary campaigns must contain information around timing. I.e. when were these IP addresses associated with the malware or campaign and when were they in active usage? IP addresses and domains are constantly getting shuffled around the Internet and are mostly useful when seen in a snapshot of time.

But let’s focus on the malware specifically which was laid out by the White House fact sheet as newly declassified information. The CSV does contain information for around 30 malicious files (Figure 5). Unfortunately, all but two have the same problems as the IP addresses in that there isn’t appropriate context as to what most of them are related to and when they were leveraged.

Figure 5: CSV of Indicators from the GRIZZLY STEPPE Report

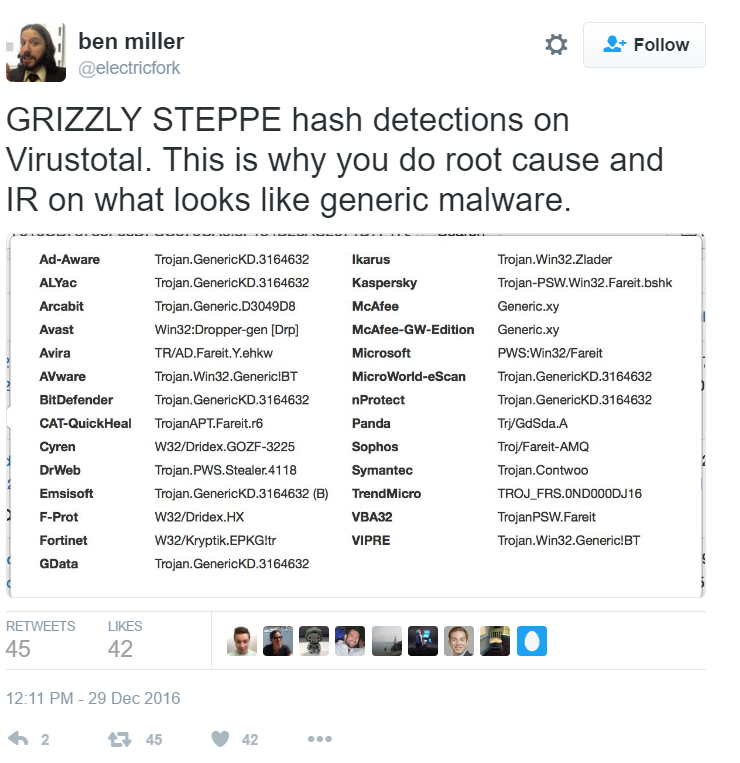

What is particularly frustrating is that this might have been some of the best information if done correctly. A quick look in VirusTotal Intelligence reveals that many of these hashes were not being tracked previously as associated to any specific adversary campaign (Figure 6). Therefore, if the DHS/FBI was to confirm that these samples of malware were part of RIS operations it would help defenders and incident responders prioritize and further investigate these samples if they had found them before. As Ben Miller pointed out, this helps encourage folks to do better root cause analysis of seemingly generic malware (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Tweet from Ben Miller on GRIZZLY STEPPE Malware Hashes

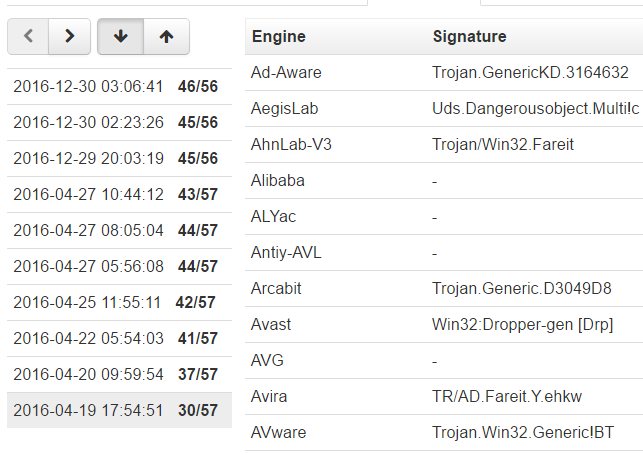

So what’s the problem? All but the two hashes released that state they belong to the OnionDuke family do not contain the appropriate context for defenders to leverage them. Without knowing what campaign they were associated with and when there’s not appropriate information for defenders to investigate these discoveries on their network. They can block the activity (play the equivalent of whack-a-mole) but not leverage it for real defense without considerable effort. Additionally, the report specifically said this was newly declassified information. However, looking the samples in VirusTotal Intelligence (Figure 7) reveals that many of them were already known dating back to April 2016.

Figure 7: VirusTotal Intelligence Lookup of One Digital Hash from GRIZZLY STEPPE

The only thing that would thus be classified about this data (note they said newly declassified and not private sector information) would be the association of this malware to a specific family or campaign instead of leaving it as “generic.” But as noted that information was left out. It’s also not fair to say it’s all “RIS” given the DHS/FBI’s inappropriate aggregation of campaign, malware, and capability names in their “Reported RIS” list. As an example, they used one name from their “Reported RIS” list (OnionDuke) and thus some of the other samples might be from there as well such as “Powershell Backdoor” which is wholly not descriptive. Either way we don’t know because they left that information out. Also as a general pet peeve, the hashes are sometimes given as MD5, sometimes as SHA1, and sometimes as SHA256. It’s ok to choose whatever standard you want if you’re giving out information but be consistent in the data format.

Or more simply stated: the indicators are not very descriptive and will have a high rate of false positives for defenders that use them. A few of the malware samples are interesting and now have context (OnionDuke) to their use but the majority do not have the required context to make them useful without considerable effort by defenders. Lastly, some of the samples were already known and the government information does not add any value – if these were previously classified it is a perfect example of over classification by government bureaucracy.

The report goes beyond indicators to include new tradecraft and techniques used by the Russian intelligence services

The report was to detail new tradecraft and techniques used by the RIS and specifically noted that defenders could leverage this to find new tactics and techniques. Except – it doesn’t. The report instead gives a high-level overview of how APT28 and APT29 have been reported to operate which is very generic and similar to many adversary campaigns (Figure 8). The tradecraft and techniques presented specific to the RIS include things such as “using shortened URLs”, “spear phishing”, “lateral movement”, and “escalating privileges” once in the network. This is basically the same set of tactics used across unrelated campaigns for the last decade or more.

Figure 8: APT28 and APT29 Tactics as Described by DHS/FBI GRIZZLY STEPPE Report

This description in the report wouldn’t be a problem for a more generic audience. If this was the DHS/FBI trying to explain to the American public how attacks like this were carried out it might even be too technical but it would be ok. The stated purpose though was for network defenders to discover new RIS tradecraft. With that purpose, it is not technical or descriptive enough and is simply a rehashing of what is common network defense knowledge. Moreover, if you would read a technical report from FireEye on APT28 or APT29 you would have better context and technical information to do defense than if you read the DHS/FBI document.

Closing Thoughts

The White House’s response and combined messaging from the government agencies is well done and the technical attribution provided by private sector companies has been solid for quite some time. However, the DHS/FBI GRIZZLY STEPPE report does not meet its stated intent of helping network defenders and instead choose to focus on a confusing assortment of attribution, non-descriptive indicators, and re-hashed tradecraft. Additionally, the bulk of the report (8 of the 13 pages) is general high level recommendations not descriptive of the RIS threats mentioned and with no linking to what activity would help with what aspect of the technical data covered. It simply serves as an advertisement of documents and programs the DHS is trying to support. One recommendation for Whitelisting Applications might as well read “whitelisting is good mm’kay?” If that recommendation would have been overlaid with what it would have stopped in this campaign specifically and how defenders could then leverage that information going forward it would at least have been descriptive and useful. Instead it reads like a copy/paste of DHS’ most recent documents – at least in a vendor report you usually only get 1 page of marketing instead of 8.

This ultimately seems like a very rushed report put together by multiple teams working different data sets and motivations. It is my opinion and speculation that there were some really good government analysts and operators contributing to this data and then report reviews, leadership approval processes, and sanitation processes stripped out most of the value and left behind a very confusing report trying to cover too much while saying too little.

We must do better as a community. This report is a good example of how a really strong strategic message (POTUS statement) and really good data (government and private sector combination) can be opened to critique due to poor report writing.