man() {

env \

LESS_TERMCAP_mb=$(printf "\e[1;31m") \

LESS_TERMCAP_md=$(printf "\e[1;31m") \

LESS_TERMCAP_me=$(printf "\e[0m") \

LESS_TERMCAP_se=$(printf "\e[0m") \

LESS_TERMCAP_so=$(printf "\e[1;44;33m") \

LESS_TERMCAP_ue=$(printf "\e[0m") \

LESS_TERMCAP_us=$(printf "\e[1;32m") \

man "$@"

}

Pretty neat, right? Let’s tear it apart, see what it’s doing, and think about how we might customize it to suit ourselves.

What even

The first and last lines define a shell function. Your shell recognizes these as commands, just like the tools that are installed on the system, but they’re written in shell language—like shell scripts, but recorded in memory rather than saved as files.

This shell function is named “man”—yes, the same name as the tool that shows manpages! Your shell will prefer your own functions over the pre-installed tools.

This function spans many lines, but runs only one command—the backslashes (\) escape the line breaks so that the shell interprets everything from “env” unto the first line not ending with a \ as one line.

That last physical line is “man "%@"”. But wait, you might ask—how doesn’t this just call itself?

This whole logical line runs a command called env. It passes env a bunch of environment variables (e.g., LESS_TERMCAP_us=…) to set, and then a command to run with that environment. That command, here, is man "%@".

env doesn’t know about shell functions. It’s not part of the shell; it’s a separate tool. So it doesn’t know about our function—the only man it knows about is the pre-installed tool called man.

So the one line that is the body of this function uses the tool called env to set up a custom environment in which to then run the tool called man.

"%@" tells the shell to insert all of the arguments to the function there, so that that line will run the real man with the arguments you passed in to the fake man—most probably, the optional section number and the manpage name.

Cool, but what’s LESS_TERMCAP_mb and such?

less is a pager—a tool that shows you a screenful at a time of some output, and waits for you to acknowledge it before showing you more. (It’s an expansion of an older pager called more.) It’s what man uses to do that—man just runs less and pipes the rendered manpage text into it.

I don’t know that the LESS_TERMCAP_xx trick is actually documented—it’s not mentioned in less’s manpage. But here’s what it does:

termcap is a database of terminal capabilities. (I won’t fault you for imagining a terminal in a cape right now.) The idea is that every kind of terminal is different (which it was, back in the day), so there needs to be a database in which you can look up whichever terminal the user has in order to find out what that kind of terminal is capable of and how to tell it to do each thing.

Each capability has a two-letter identifier, and maps to a string of characters. Here are the capabilities used in the Gist, as defined in the aforelinked manpage:

- mb

- Start blinking

- md

- Start bold mode

- me

- End all mode like so, us, mb, md and mr

- so

- Start standout mode

- se

- End standout mode

- us

- Start underlining

- ue

- End underlining

“Standout” mode, in case you’re wondering, is inverse video: use the assigned foreground color as the background color and vice versa.

zsh has a built-in command called echotc that lets us play with these records. For example:

% echotc us && echo -n 'This should be underlined' && \

echotc ue && echo ' and this should not.'This should be underlined and this should not.Yup, us starts underlining and ue ends underlining!

So when we want something underlined (for example), the us and ue entries in our terminal’s termcap record are what we need to send to the terminal to start and end underlining that section of text.

And less, it seems, provides this handy way to override those entries using environment variables. We can make us and ue and any other termcap string do whatever we want!

What are these strings you speak of?

Yes, just what are these termcap strings doing now?

All of them follow a similar format:

\e[(one or more numbers separated by semicolons)m

The \e[ essentially tells the terminal to start listening for a command that will change its behavior. m is actually the command here; all the inputs to the command come before it. The m command tells the terminal to change how it renders subsequent text until further notice.

(\e is the ASCII/Unicode character U+001B ESCAPE, just in case you were wondering. In other languages, you might refer to it as \x1b or \033.)

These are ANSI escape sequences, which come in a lot more varieties than these, but these are the most common. The m command takes a list of arguments, all of which are numbers, separated by semicolons:

- 0

- Reset to standard configuration

- 1

- Bold

- 31

- Set foreground color to red

- 32

- Set foreground color to green

- 33

- Set foreground color to yellow

- 44

- Set background color to blue

There are more than just those options for our foreground and background colors, of course! We’ll see more shortly.

So, for example, the first variable:

LESS_TERMCAP_mb=$(printf "\e[1;31m") \says that when we want to start blinking, display bold red text instead.

Customizing

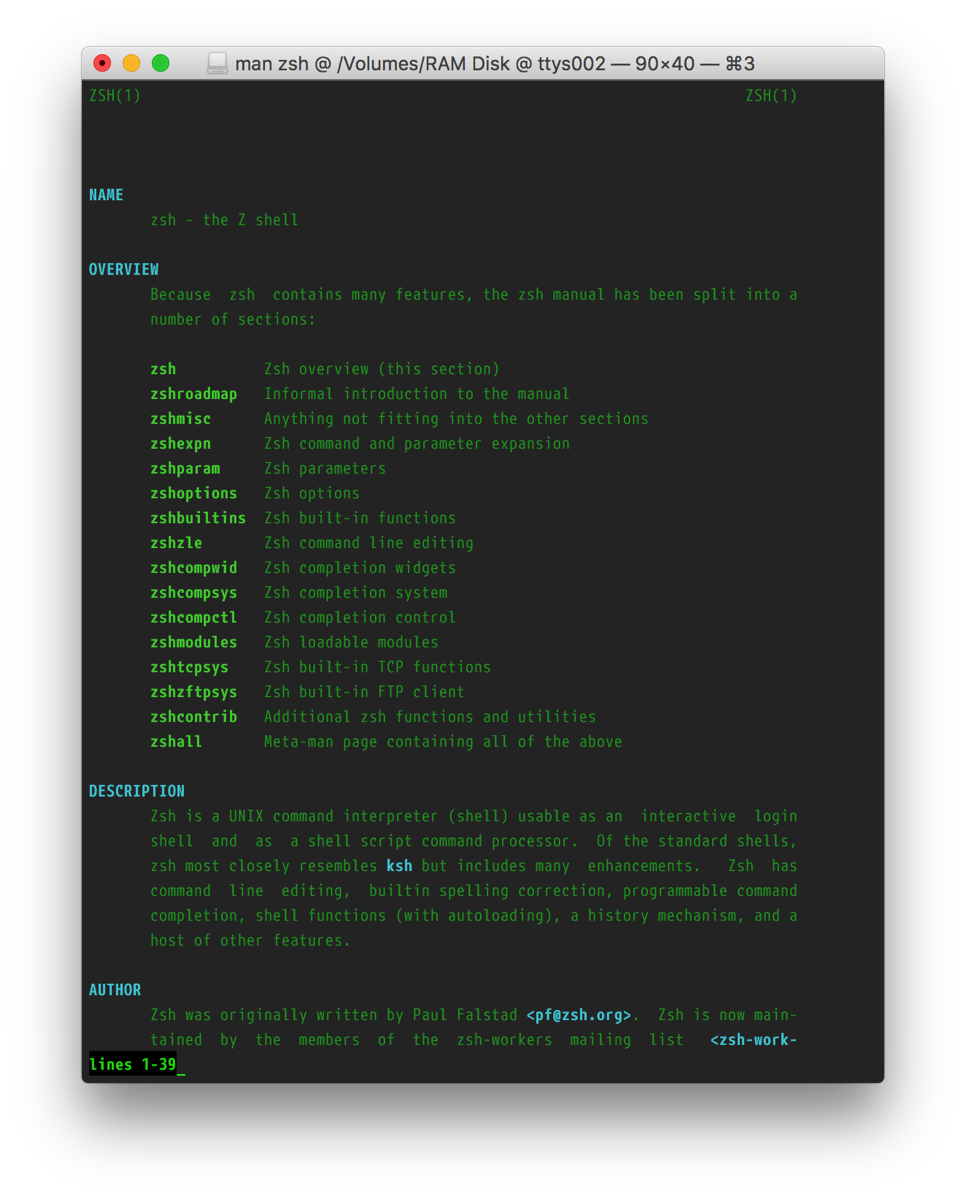

Let’s start by seeing it in my own Terminal theme:

I’m also going to make one change to start with:

man() {

env \

LESS_TERMCAP_mb=$'\e[1;31m' \

LESS_TERMCAP_md=$'\e[1;31m' \

LESS_TERMCAP_me=$'\e[0m' \

LESS_TERMCAP_se=$'\e[0m' \

LESS_TERMCAP_so=$'\e[1;44;33m' \

LESS_TERMCAP_ue=$'\e[0m' \

LESS_TERMCAP_us=$'\e[1;32m' \

man "$@"

}$(…) runs a command and is replaced with the output, so $(printf …) replaces the $(…) with the string that printf prints.

That’s redundant! We can simplify this to $'…', which will let us have the \e sequences without calling the shell built-in function printf for every one of these.

OK, let’s start with…

The bountiful rainbow of color

We have a lot more than those four colors to choose from. The basic ANSI set is 16, and most terminal emulators have supported 256-color sequences for years now. That Wikipedia article has charts of all the different color codes; here are the basic groups:

- 30–37

- Foreground color, dark

- 90–97

- Foreground color, bright

- 40–47

- Background color, dark

- 100–107

- Background color, bright

- 38;5;###

- Set foreground color to color ### (256-color extension)

- 48;5;###

- Set background color to color ### (256-color extension)

Now that we have more colors to work with, let’s explore…

What things in a manpage use which capabilities?

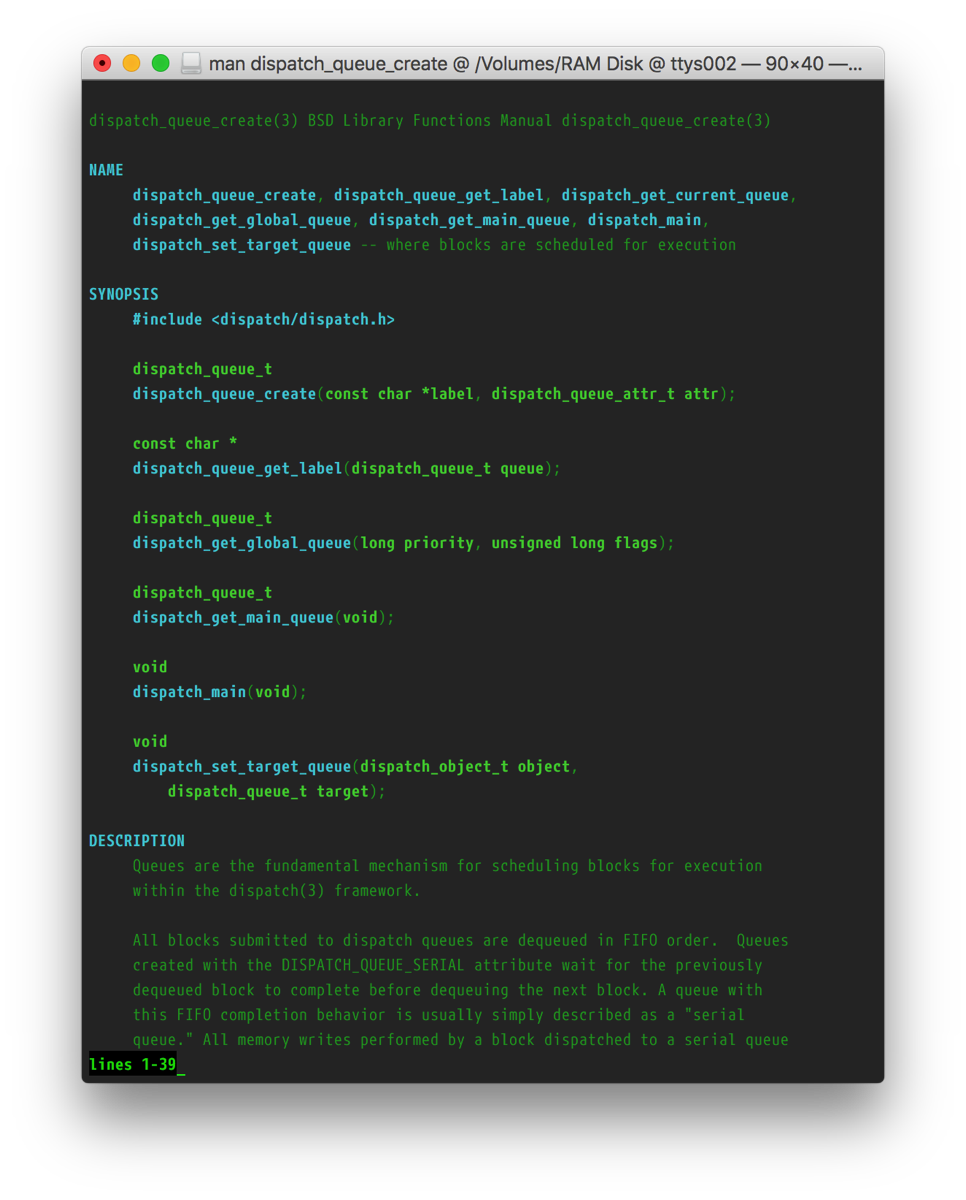

I changed the function so that every capability got a unique character—i.e., I changed blinking (mb) to 35, which is fuchsia—and then looked up a few things.

It doesn’t seem like anything uses blinking.

That leaves bold (mb), underline (us), and standout/inverse (so).

man and less use:

- bold for headings, command synopses, and code font

- underline for proper names (for example, “termcap” and “terminfo” in the termcap manpage), variable names (“name”, “bp”, “id”, etc.), and type names in some manpages (such as

dispatch_queue_create(3)) - inverse for the prompt at the bottom

(Some of these are more consistent than others. This is the problem with looking things from the styling end rather than the semantic end—which is why web developers had to invent CSS!)

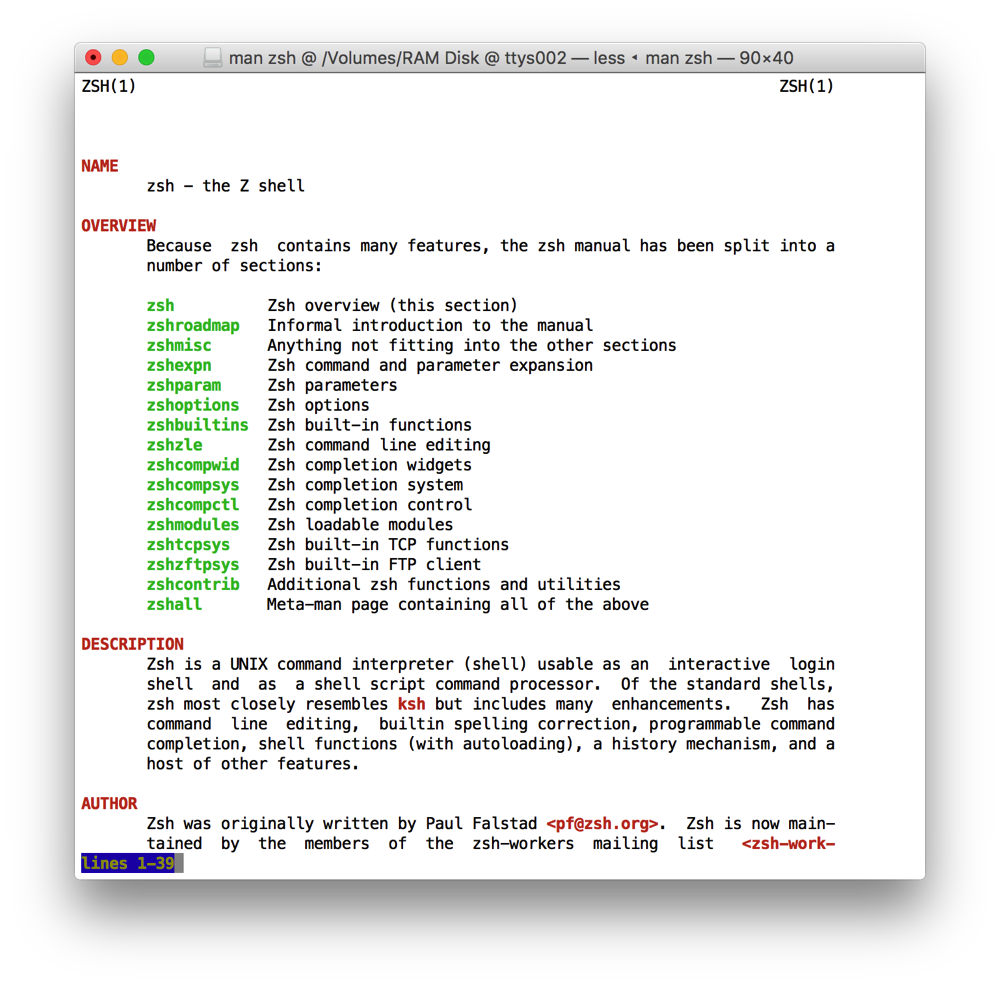

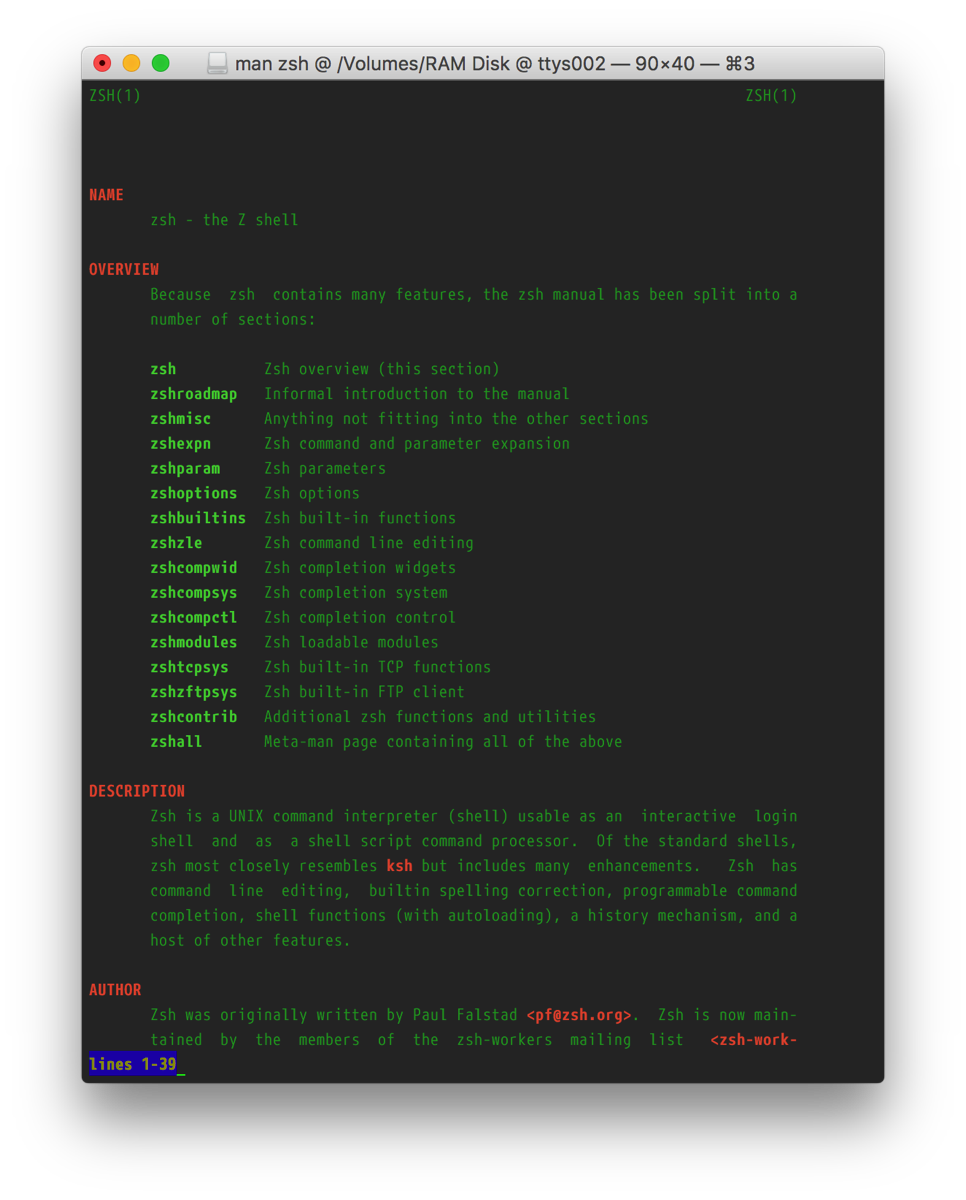

My own changes

- Cut out

mbentirely, since it seems unused - Change

mdfrom setting31(red) to setting36(cyan) for the foreground color - Change

sofrom44;33(yellow on blue) to40;92(bright green on black)

I left the us override alone; I think the green generally works where that’s used.

So here’s what that looks like: